It is difficult to take good pictures without having a solid understanding of ISO, Shutter Speed and Aperture – the Three Kings of Photography, also known as the “Exposure Triangle“.

While most cameras have “Auto” modes that automatically pick the right shutter speed, aperture and even ISO for your exposure, using an Auto mode puts limits on what you can achieve with your camera. In many cases, the camera has to guess what the right exposure should be by evaluating the amount of light that passes through the lens. Thoroughly understanding how ISO, shutter speed and aperture work together allows photographers to fully take charge of the situation by manually controlling the camera.

Knowing how to adjust the settings of the camera when needed, helps to get the best out of your camera and push it to its limits to take great photographs.

Let’s quickly review a summary of the Exposure Triangle as a refresher:

- Shutter Speed – the length of time a camera shutter is open to expose light into the camera sensor. Shutter speeds are typically measured in fractions of a second, when they are under a second. Slow shutter speeds allow more light into the camera sensor and are used for low-light and night photography, while fast shutter speeds help to freeze motion. Examples of shutter speeds: 1/15 (1/15th of a second), 1/30, 1/60, 1/125.

- Aperture – a hole within a lens, through which light travels into the camera body. The larger the hole, the more light passes to the camera sensor. Aperture also controls the depth of field, which is the portion of a scene that appears to be sharp. If the aperture is very small, the depth of field is large, while if the aperture is large, the depth of field is small. In photography, aperture is typically expressed in “f” numbers (also known as “focal ratio”, since the f-number is the ratio of the diameter of the lens aperture to the length of the lens). Examples of f-numbers are: f/1.4, f/2.0, f/2.8, f/4.0, f/5.6, f/8.0.

- ISO – a way to brighten your photos if you can’t use a longer shutter speed or a wider aperture. It is typically measured in numbers, a lower number representing a darker image, while higher numbers mean a brighter image. However, raising your ISO comes at a cost. As the ISO rises, so does the visibility of graininess/noise in your images. Examples of ISO: 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600.

Also, take a look at this article if you would like to understand what exposure actually means.

And if you’re more of a visual learner, we recently published a comprehensive, beginner-friendly video on this exact same topic:

Table of Contents

1) How Do Shutter Speed, Aperture and ISO Work Together to Create an Exposure?

To have a good understanding about exposure and how shutter speed, aperture and ISO affect it, we need to understand what happens within the camera when a picture is taken.

As you point your camera at a subject and press the shutter button, the subject gets into your camera lens in a form of light. If your subject is well-lit, there is plenty of light that travels into the lens, whereas if you are taking a picture in a dim environment, there is not much light that travels into the lens. When the light enters the lens, it passes through various optical elements made of glass, then goes through the lens “Aperture” (a hole inside the lens that can be changed from small to large). Once the light goes past the lens aperture, it then hits the shutter curtain, which is like a window that is closed at all times, but opens when needed. The shutter then opens in a matter of milliseconds, letting the light hit the camera sensor for a specified amount of time. This specified amount of time is called “Shutter Speed” and it can be extremely short (up to 1/8000th of a second) or long (up to 30 seconds). The sensor then gathers the light, and your “ISO” brightens the image if necessary (again, making grain and image quality problems more visible). Then the shutter closes and the light is completely blocked from reaching the camera sensor.

To get the image properly exposed, so that it is not too bright or too dark, Shutter Speed, Aperture and ISO need to play together. When lots of light enters the lens (let’s say it is broad daylight with plenty of sunlight), what happens when the lens aperture/hole is very small? Lots of light gets blocked. This means that the camera sensor would need more time to collect the light. What needs to happen for the sensor to collect the right amount of light? That’s right, the shutter needs to stay open longer. So, with a very small lens aperture, we would need more time, i.e. longer shutter speed for the sensor to gather enough light to produce a properly exposed image.

Now what would happen if the lens aperture/hole was very big? Obviously, a lot more light would hit the sensor, so we would need a much shorter shutter speed for the image to get properly exposed. If the shutter speed is too low, the sensor would get a lot more light than it needs and the light would start “burning” or “overexposing” the image, just like magnifying glass starts burning paper on a sunny day. The overexposed area of the image will look very bright or pure white. In contrast, if the shutter speed is way too high, then the sensor is not able to gather enough light and the image would appear “underexposed” or too dark.

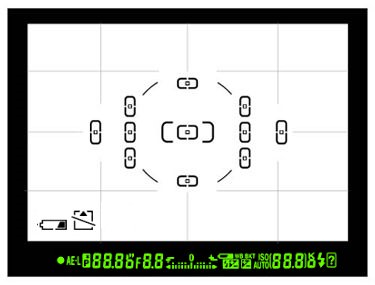

Let’s do a real-life example. Grab your camera and set your camera mode to “Aperture Priority“. Set your lens aperture on your camera to the lowest possible number the lens will allow, such as f/1.4 if you have a fast lens or f/3.5 on slower lenses. Set your ISO to 200 and make sure that “Auto ISO” is turned off. Now point your camera at an object that is NOT a light source (for example a picture on the wall) then half-press the shutter button to acquire correct focus and let the camera determine the optimal exposure settings. Do not move your camera and keep pointing at the same subject! If you look inside the camera viewfinder now or on the back LCD, you should see several numbers. One of the numbers will show your aperture, which should be the same number as what you set your aperture to, then it should show your shutter speed, which should be a number such as “125” (means 1/125th of a second) and “200”, which is your sensor ISO.

Write down these numbers on a piece of paper and then take a picture. When the picture comes up on the rear LCD of your camera, it should be properly exposed. It might be very blurry, but it should be properly exposed, which means not too bright or too dark. Let’s say the settings you wrote down are 3.5 (aperture), 125 (shutter speed) and 200 (ISO). Now change your camera mode to “Manual Mode“. Manually set your aperture to the same number as you wrote down, which should be the lowest number your camera lens will allow (in our example it is 3.5). Then set your shutter speed to the number you wrote down (in our example it is 125) and keep your ISO the same – 200. Make sure your lighting conditions in the room stay the same.

Point at the same subject and take another picture. Your results should look very similar to the picture you took earlier, except this time, you are manually setting your camera shutter speed, instead of letting your camera make the guess. Now, let’s block the amount of light that is passing through the lens by increasing the aperture and see what happens. Increase your aperture to a larger number such as “8.0” and keep the rest of the settings the same. Point at the same subject and take another picture. What happened? Your image is too dark or underexposed now! Why did this happen? Because you blocked a portion of the light that hits the sensor and did not change the shutter speed. Because of this, the camera sensor did not have enough time to gather the light and therefore the image is underexposed. Had you decreased the shutter speed to a smaller number, this would not have happened. Understand the relationship?

Now change your aperture back to what it was before (smallest number), but this time, decrease your shutter speed to a much smaller number. In my example, I will set my shutter speed to 4 (quarter of a second) from 125. Take another picture. Now your image should be overexposed and some parts of the image should appear too bright. What happened this time? You let your lens pass through all the light it can gather without blocking it, then you let your sensor gather more light then it needs by decreasing the shutter speed. This is a very basic explanation of how aperture and shutter speed play together.

So, when does ISO come into play and what does it do? So far, we kept the ISO at the same number (200) and didn’t change it. Remember, ISO means sensor brightness. Lower numbers mean lower brightness, while higher numbers mean higher brightness. If you were to change your ISO from 200 to 400, you would be making the photo twice as bright. In the above example, at aperture of f/3.5, shutter speed of 1/125th of a second and ISO 200, if you were to increase the ISO to 400, you would need half the time to properly expose the image. This means that you could set your shutter speed to 1/250th of a second and your image would still come out properly exposed. Try it – set your aperture to the same number you wrote down earlier, use a shutter speed that is twice as fast, then change your ISO to 400. It should look the same as the first image you took earlier. If you were to increase the ISO to 800, you would need to again use a shutter speed that’s twice as fast, from 1/250 to 1/500.

As you can see, increasing ISO from 200 to 800 will allow you to shoot at higher shutter speeds and in this example increase it from 1/125th of a second to 1/500th of a second, which is plenty of speed to freeze motion. However, increasing ISO comes at a cost – the higher the ISO, the more noise or grain it will add to the picture.

Basically, this is how the Three Kings work together to create an exposure. I highly recommend practicing with your camera more to see the effects of changing aperture, shutter speed and ISO.

2) What Camera Mode Should I Be Using?

As I pointed out in my “Understanding Digital Camera Modes” article, I recommend using “Aperture Priority” mode for beginners (although any other mode works equally well, as long as you know what you are doing).

In this mode, you set your lens aperture, while the camera automatically guesses what the right shutter speed should be. This way, you can control the depth of field in your images by changing the aperture (depth of field also depends on other factors such as camera to subject distance and focal length).

There is absolutely nothing wrong with using “Auto” or “Program” modes, especially considering the fact that most modern mirrorless and DSLRs give the photographer pretty good control by allowing to override the shutter speed and aperture in those modes. But most people get lazy and end up using the Auto/Program modes without understanding what happens inside the camera, so I highly recommend to learn how to shoot in all camera modes.

3) What ISO Should I Set My Camera To?

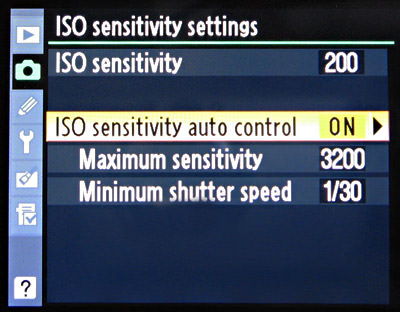

If your camera is equipped with an “Auto ISO” feature (known as “ISO Sensitivity Auto Control” on Nikon bodies), you should enable it, so that the camera automatically guesses what the right ISO should be in different lighting conditions. Auto ISO is worry-free and it works great for most lighting conditions!

Set your “Minimum ISO/ISO Sensitivity” to its lowest value which is typically 80 or 100, then set your “Maximum ISO/Maximum Sensitivity” to the highest value, which is typically 25,600 or 51,200. Set the “Minimum Shutter Speed” to 1/100th of a second if you have a short lens below 100mm and to a higher number if you have a long lens.

Basically, the camera will watch your shutter speed and if it drops below the “Minimum Shutter Speed”, it will automatically increase the ISO to a higher number, to try to keep the shutter speed above this setting. The general rule is to set your shutter speed to the largest focal length of your lens. For example, if you have a Nikon 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6 zoom lens, set your minimum shutter speed to 1/300th of a second. Why? Because as the focal length of the lens increases, so do the chances of having a camera shake that will render your images blurry.

But this rule doesn’t always work, because there are other factors that all play a role in whether you will introduce camera shake or not. Having shaky hands and improperly holding the camera might cause extra camera shake, while having a lens with Vibration Reduction (also known as Image Stabilization) might actually help to decrease camera shake. Either way, play with the “Minimum Shutter Speed” option and try changing numbers and see what works for you.

If you do not have an “Auto ISO” option in your camera, then start out with the lowest ISO and see what shutter speeds you are getting. Keep on increasing the ISO until you get to an acceptable shutter speed.

4) Exposure Compensation

Another great feature of all modern mirrorless and DSLRs, is the ability to control the exposure by using the “exposure compensation” feature. Except for manual mode without Auto ISO, exposure compensation works great for all camera modes.

Whether you are shooting in Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority or Auto/Program modes, dialing the exposure compensation up or down (plus to minus) will allow you to regulate the exposure and override the camera-guessed settings. If you find your image (or parts of your image) underexposed or overexposed, you can use exposure compensation to adjust the exposure without manually changing the aperture or shutter speed. This is especially useful if you’ve got zebras or some other sort of overexposure indicator on a mirrorless camera.

5) Should I Use Flash or Increase ISO?

It really depends on what you are taking a picture of. Sometimes it is not possible to use your built-in camera flash in a low-light environment. For example, if your subject is standing far away, you might not be able to reach the subject with your flash. In that case, the only solution is to either come closer to the subject, or turn off flash completely and use a higher ISO.

Obviously, for landscape or architectural photography, you should always turn off your flash, because it will not be able to brighten up the entire scene. So in a low-light situation, the only two options are to either increase the ISO so that you can shoot hand-held, or set the camera to the lowest ISO and use a tripod.

In other cases such as macro photography, using an off-camera flash is very helpful because there is so little light in many macro scenarios and detail really starts to disintegrate at macro distances.

6) What are “Full Stops”?

Have you ever heard of a term “full stop” in photography? Each of the increments between ISO numbers is called “a full stop” in photography. For example, there is one full stop between ISO 100 and ISO 200, while there are two full stops between ISO 100 and ISO 400. How many stops are there between ISO 100 and ISO 1600? That’s right, four full stops of light.

Why do you need to know about stops? Because you might see it in photography literature or photographer might mention stops and it is sometimes confusing to understand what it truly means. But the term “full stop” does not just apply to ISOs – the same concept is there for shutter speed and aperture. It is easy to remember full stops between shutter speeds, because you just start from one and divide the number by two: 1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/15, 1/30, 1/60, 1/125, 1/250, 1/500, 1/1000, etc. That’s because twice as much time lets in twice as much light. Obviously, the numbers are rounded (starting from 1/15, which should be 1/16) to make it easy for photography.

It is harder to memorize stops in apertures, because the numbers are computed differently: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, etc. To read more about stops, please see our detailed Exposure Stops article.

7) Specific Examples and Case Scenarios

Let’s now go over what you could do in your camera to properly expose an image in different lighting conditions.

- What should I do in low-light situations? Use Aperture-Priority mode, set your aperture to the lowest possible number. Be careful if you have a fast lens such as Nikon 50mm f/1.4, because setting aperture to the lowest number (f/1.4) will make the depth of field very shallow. Set your “Auto ISO” to “On” (if you have it) and make sure that the maximum ISO and minimum shutter speed are both defined, as shown in section 3. If after increasing your ISO you are still getting small shutter speeds (which means that you are in a very dim environment), your only other options are to either use a tripod or a flash. If you have moving subjects that need to be “frozen”, you will have to use flash.

- What do I need to do to freeze action? First, you will need plenty of light. Freezing action during the broad daylight is easy, whereas it is extremely tough to do it in low-light situations. Assuming you have plenty of light, make sure that your aperture is set to the lowest number (again, be careful about depth of field), then set your “Auto ISO” to “On” (if you have it) and set your minimum shutter speed to a really high number such as 1/500th or 1/1000th of a second. For my bird photography, I try to keep shutter speeds at 1/1000th of a second and faster:

- What settings do I need to change to create a motion blur effect? Turn off Auto ISO and set your ISO to the lowest number. If the shutter speed is too fast and you still cannot create motion blur, increase aperture to a higher number until the shutter speed drops to a low number below 1/100-1/50 of a second.

- What do I do if I cannot get proper exposure? The image is either too dark or too bright. Make sure that you are not shooting in Manual Mode. Set your camera meter to “Evaluative” (Canon) or “Matrix” (Nikon). If it is already set and you are still getting improper exposure, it means that you are probably taking a picture where there is a big contrast between multiple objects (for example bright sky and dark mountains, or sun in the frame) – whatever you are trying to take a picture of is confusing the meter within your camera. If you still need to take a picture, set your camera meter to “Spot” and try to point your focus point to an area that is not too bright or too dark. That way you get the “sweet middle”.

- How can I isolate my subject from the background and make the background (bokeh) look soft and smooth? Stand closer to your subject and use the smallest aperture on your lens. Some lenses can render background much better and smoother than others. If you do not like the bokeh on yours, consider getting a good portrait lens such as the Nikon 50mm f/1.4 or the Nikon 85mm f/1.4, which is considered to be one of the best lenses when it comes to bokeh.

- How can I decrease the amount of noise/grain in my images? Turn off “Auto ISO” and set your ISO to the base ISO of the camera (ISO 100 on Canon and ISO 200 on Nikon).

This is a very good website it is better than. Y teacher my teacher doesn’t teach anything he just tells us to read everything on this website I hate my teacher he also teaches yyollowball so half the time he’s not even there

Thank you for applicable tips about camera using, particularly it’s convenient for the beginners

Thank you! This sets the foundation for me with the working relationship between Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO.

Learning curve was excellent.. Short and precise.. Thanks.

I have a question about wildlife photography. If I am photographing a dark bear in lots of brightly sun lit water, so dark subject with confusing bright background, can I stay on evaluative and increase my exposure compensation while focusing on the bear? Will this balance the image or must I only do spot metering.

You can do either. Just be aware that spot metering will blow out the water a lot, so in that case you may have to decrease exposure compensation. Personally, I would stick with an exposure mode that gets closest to the exposure you want, and then use exposure compensation. So your guess about evaluative metering is a good one. In addition, this is a case where postprocessing can help a lot, so don’t be afraid to underexpose your subject and boost shadows in post using tone curves or other techniques in Lightroom or other software that you use.

The only thing I am sorry that I didn’t discover this tutorial earlier. You have an amazing description of those basic features. Thank you so much.

Outstanding tutorial. Thanks so much for this.

Hi, please am still a beginner. This depth of field and how to create it and how my setting is suppose to be, is still really confusing.

Is my aperture expected to increase in order to get a good dof or decrease, what are u guys advice to what am to set my ISO and shutter speed in order to compliment everything..

Great refresher after putting down Nikon….love examples to try -helps learn concepts again.

Thank you, appreciating this sharing.