In my photography classes I often get asked, “What is a long exposure?” Many beginning photographers want me to give them a definitive shutter speed with my explanation. However, long exposures are not only subject driven, they are largely based on the artistic vision you have for your photograph. Panning, light painting and night photography all make use of long exposures. However, these techniques are subjects of a future article. Today I would like to discuss “really” long exposures, exposures in excess of several minutes. These types of exposures create surreal, dreamlike images. They use neutral density filters (think sunglasses for your lens) to extend exposure times far in excess of what could be achieved by simply decreasing ISO and stopping down your aperture.

Table of Contents

1) Why Use Such Long Exposures?

Long exposures create a sense of mystery. They softly blur anything that moves. Clouds become streaks, water takes on a cotton candy like appearance and people either disappear or become ghosted figures. But the most important perk to using a very long exposure is that it simplifies composition. It strips down an image to the basics: lines, shapes, and tonality.

2) Equipment

Besides the obvious (DSLR camera, wide angle lens, tripod, cable/remote release, fully charged batteries), you will also need solid ND filters. ND filters decrease the amount of light entering the lens. They are what allow you to slow your shutter speeds from fractions of a second, to lengths in excess of several minutes, even during the day.

Other items you need include:

- Exposure conversion chart or app (there are lots of free long exposure apps available for your cell phone, search “long exposure calculators”)

- Something to cover your camera to stop light leaks

- A timer (I use my phone)

- Good book, long playlist and lots of patience!

3) Solid ND Filters

ND is short for Neutral Density, sometimes referred to as a “grey filter” or “dark glass”. A perfect ND filter should filter all the visible colours of light equally. This means that an ND filter shouldn’t have any effect on the colours in your image. Unfortunately, with very long exposures this is not always true. If you are taking exposures, in excess of five minutes, you will sometimes pick up a pink or magenta colour cast. This is because higher wavelength light (infrared) is not completely blocked by some ND filters and builds up on the sensor. Adjusting the white balance during post will usually repair this pink cast. In addition, many filter manufacturers now combine ND filters with IR blocking capability. To avoid this colour cast completely, many photographers choose to convert their long exposures into black and white.

This first photo shows the unedited image. Notice its magenta cast. The second and third images are the final colour and black & white edited versions.

You may have heard of split or graduated ND filters. These filters are clear on the bottom half and have a dark band on the top half. Split ND filters are used when the dynamic range of the scene is too high to record. They are often used in landscapes to darken a bright sky. For long exposure photography, you need solid ND filters. These filters, as the name implies, are a solid dark colour.

Here are Lee’s rectangular two and three stop soft graduated ND filters along with their Big Stopper 10-stop solid ND filter and rectangular filter holder.

3.1) ND Filter Strengths

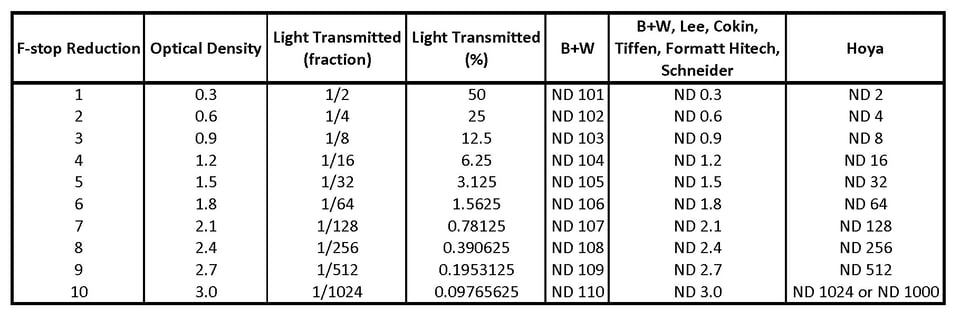

ND filters are rated according to how much light they block. The darker the filter, the less light is transmitted through it. Less light corresponds to longer exposures. When you choose an ND filter you will find that different manufacturers use different systems to describe the strength of their filters. This can sometimes cause a bit of confusion. The three rating numbers you will see used are: filter strength, light reduction factor and optical density.

Filter strength is probably the simplest of the rating systems to understand. This system states the number of stops of light that the filter blocks. This system is used by Singh-Ray for its threaded ND filters. For example, Singh-Ray’s Mor-Slo 10-Stop ND Filter has a 10-stop reduction in light. This rating system is also used by B+W, although the factor is slightly hidden. B+W identifies its filters as ND1xx, where xx is the filter strength. A B+W ND106 is a 6-stop filter. B+W actually uses both filter strength and optical density (see below) to describe the strength of their filters.

The light reduction factor is a number that describes the amount of light that is transmitted through the filter. For example; an ND4 lets ¼ of the light pass through it. An ND8 lets 1/8 of the light pass through it. Hoya uses this system. For example, a Hoya ProND2 Filter lets ½ the light pass through it.

The third number used to describe the opacity of an ND filter is optical density. Mathematically, optical density is the log(base 10) of the factor that the light is reduced by. A 1-stop filter reduces light by a factor of 2 (allowing ½ of the light to be transmitted). Thus, its optical density would be the log(2) which is 0.3. For a 4-stop filter, the light is reduced by a factor of 16 (allowing 1/16 of the light to be transmitted). Therefore its optical density would be log(16) which is 1.2. Every multiple of 0.3 of the optical density reduces the light transmitted by one stop. Cokin, Tiffen, Formatt Hitech, Lee and B+W use this system of rating. A Tiffen 0.6 ND filter is a 2-stop filter. Lee’s Big Stopper Neutral Density 3.0 filter is a 10-stop filter. Lastly, Formatt Hitech’s Firecrest ND 3.9 filter is a whopping 13-stop filter!

To simplify comparison, here is a table summarizing how the major filter manufacturers rate and name their ND filters.

3.2) ND Filter Types

ND filters come in two varieties, circular screw-in and rectangular. The later requires a holder that attaches to the front of your lens. You then slide the rectangular filter into the holder. I prefer the screw-in variety because they are easier to attach and have less chance of light leakage.

When you are buying an ND filter, buy one that fits your largest diameter lens. If you have smaller diameter lenses that you would like to use the filter on, buy a step-up ring. A step-up ring allows you to couple the larger diameter filter threads of the filter to smaller diameter threads on a lens.

Here is a Tiffen 62-77mm Step-Up Ring. It allows you to use a 77mm diameter filter on a 62mm diameter lens.

3.3) What Strength ND Filter Do I Need?

If you plan on taking your long exposures during the day, I would suggest purchasing a 10-stop and 6-stop filter. These can be stacked together to produce a total of 16-stops. A circular polarizer is equivalent to approximately a 2-stop reduction in light and can also be stacked with your ND filters. Although you can stack multiple filters together, do not stack more than two to avoid vignetting.

Here are two ND filters. The darker one is a B+W ND106 (6-stop), the lighter is a Tiffen ND0.6 (2-stop). Their intersection is 8-stops.

4) Good Subjects

When you are looking for subjects that make for good long exposure photographs, pick a scene that has both stationary objects and something that moves. The movement can be found in water, clouds, traffic and people. Here are a few examples of great subjects.

• Pilings or piers with a very low distant horizon

• Dock or harbor – be careful with moored boats “bobbing” in the water, as they will appear as ghosts!

• Tight shots of buildings showing only walls and clouds

• Wide landscapes with rolling fog or dramatic clouds

• Isolated old buildings with blowing grass and moving clouds

5) How to Take Very Long Exposures

Long exposures take a long time! They are the exact opposite of “spray and pray” photography. Long exposures take some thought and planning before you press the shutter.

5.1) Composition

When you arrive at your shoot location, take your time deciding where the best vantage point is. I will often walk around and take several regular exposures and evaluate these on the back of my camera. Should I move a bit to the left or right? How high do I want my horizon? Are there any distracting elements at the edges of my frame? Once you are satisfied with your composition, set up your tripod and attach your camera. You may still need to do a little tweaking of the composition before your final long exposure.

Once you are set up on your tripod, attach a cable release or remote trigger and select the lowest native ISO on your camera. Make sure that your vibration reduction is turned off. Double-check the framing of your shot.

5.2) Choose Your Aperture

With your camera in aperture priority, select a relatively small aperture (f/8 or smaller). Apertures between f/8 and f/11 are typically the sweet spot for a lens. Assuming you are using a wide-angle lens (24mm or wider), these apertures will give you lots of depth of field and sharp focus from edge to edge. I try to avoid using f/22 and smaller apertures to minimize diffraction. Diffraction is the softness that occurs due to light bending around the diaphragm blades. It becomes much more apparent at very small apertures.

5.3) Focus

Switch your camera to manual focus and focus your shot. I usually focus 3-6 feet in front of the camera. This assures that you have both your foreground and background sharply in focus. You can find all sorts of apps that can help you determine how far into the shot to focus for maximum depth of field. However, with digital, it is easy to check your focus on the back of the camera. Be aware though, diffraction may become unacceptable at very small apertures, as I mentioned above.

Take a photo and check your image for focus. If necessary, readjust the focus. It is a good idea to place a piece of gaffers tape over the focus ring to ensure it doesn’t accidently get moved once you have established focus.

All of this composition and focus work is done without the ND filter(s) attached. You will find that with ND filters on the front of your lens, you will not be able to see out your viewfinder! The display will be too dark to compose, let alone focus.

5.4) Determine Long Exposure Shutter Speed

The next step is to determine how long your exposure should be once you attach the ND filters. After you put the ND filters on your lens, your camera will not be able to meter. You must calculate the correct exposure based on the strength of your ND filters and the pre-ND exposure.

Before attaching the filters, measure the exposure using a spot meter or your camera’s internal meter (press the shutter half way down). I often take a couple of “regular” exposures at this time and evaluate my histogram to confirm that the exposure is correct before attaching the ND filters. Note the shutter speed.

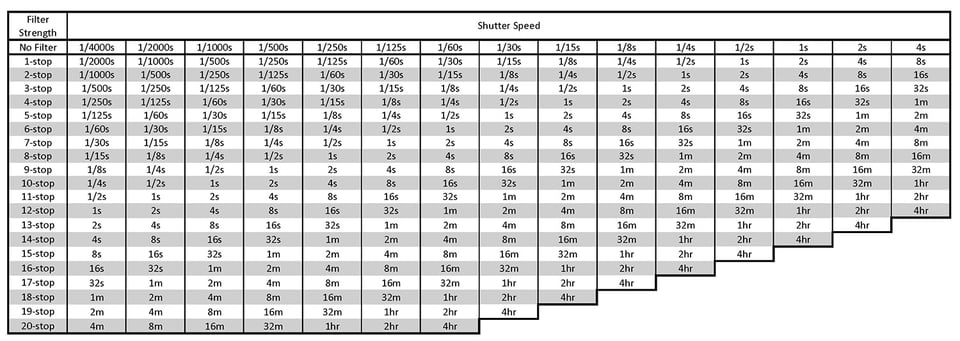

Recall that a stop of light is the doubling or halving of the total amount of light that hits the sensor. A three-stop ND filter for example, extends your shutter speed by three full stops. So, if your original metering gave you a shutter speed of 1/125s, with a three-stop filter you could increase that to 1/15s (1/125s to 1/60s is one stop, 1/60s to 1/30s is two stops, and 1/30s to 1/15s is three stops). However, to really slow the exposure you will want around 16 stops of light reduction. With a 16-stop filter, the math can get a bit tedious, especially since I don’t have 16 fingers! Use this chart to help you convert. In the ‘No Filter’ row, find your metered shutter speed. From here, drop down to the row describing the ND filter strength you are using. Where this row and column intersect is your new converted shutter speed. Alternatively, download an exposure calculator onto your phone. With a 16-stops filter (a 6-stop and 10-stop stacked together), that 1/125s initial exposure turns into 8 minutes!

5.5) Taking the Shot

With your filtered shutter speed calculated, switch the camera to manual mode. Set the aperture you chose in section 5.2. Set your shutter speed to bulb. Making sure that your focus is correct, and that your tripod head is securely locked down, carefully attach your ND filter or a combination of filters.

To prevent any light from leaking into the camera, cover your camera and lens with a dark cloth or jacket and secure it with clips. During very long exposures, light has a way of sneaking into your camera, particularly through the viewfinder.

In this shot of Cape Neddick Lighthouse in Maine I forgot to cover my camera. Even though this is not technically a “really” long exposure, it was still long enough to allow light to seep in through the viewfinder.

You are now ready to take the picture. Using a cable release, press and lock the shutter release. Set a timer on your watch, sit back, relax, and plug in your music while you wait. I often use this time to wander around and look for new compositions. When your timer goes off, unlock the cable release to stop the exposure. Don’t worry if your exposure is not exact. With exposures of several minutes, leaving the shutter open a few extra seconds will not affect your overall exposure.

6) Tips

Check your histogram. I often find my images need a longer exposure than what I initially calculated. If your histogram is bunched up on the left, increase your exposure time by a stop. That means doubling the length of the exposure. If you took an eight-minute exposure, try 16 minutes.

I usually shoot three shots of each image and bracket each one by ½ or a full stop, depending on the dynamic range of the composition. In Photoshop you can merge the images using layers and layer masks.

Make sure you are shooting in raw. This will give you the most latitude when you are processing your images.

Turn off the long-exposure noise reduction in your camera. Yes, with these long exposures, your sensor will heat up, and you will see additional noise and hot pixels in your images. However, using the long exposure noise reduction doubles your exposure time, and software like Lightroom already eliminates hot pixels automatically.

To be specific, long exposure noise reduction takes a second photo immediately after the first, only this time the shutter remains closed. This ‘dark frame’ is used to electronically subtract the noise from the initial photograph. I enjoy the slower pace of long exposure photography, but not enough to double the length of each exposure!

Let your sensor cool off a few minutes between exposures. This will help to mitigate some of the noise and hot pixels that build up when the sensor gets hot.

Make sure you have a fully charged battery and a couple of spare ones in your bag. Long exposures, especially in colder weather, consume batteries very quickly.

If you want to create a ghostly image, walk into your frame and stand still for about one third of the exposure. This allows just enough light to reflect off you and register on the sensor, but not enough to render you as a solid object. In this photo the seagulls were not in the photo for the entire exposure. And when they landed, they did not stand still. Notice how they appear as ghosts.

7) Final Thoughts

I know that some of you will ask me why I don’t just take a series of shorter exposure images and stack them together in Photoshop. Surely this will give a noise free image. Nasim just addressed this question in his recent article “Are Polarizing, ND and UV Filters Useless?” I completely agree with him, and direct you to his article. A large aspect of creating these images is to slow down. Getting out of the rapid-fire philosophy and enjoying the moment is what very long exposures are about.

Creating images using very long exposures are a refreshing change from shooting “regular” photographs. They force you to think very carefully about your composition. A single shot can take upwards of 45 minutes to an hour from conception to completion, including bracketing. It reminds me of the film days when every shot was carefully thought out and calculated. You could not afford to shoot hundreds of images hoping for one keeper.

I hope this article addresses some of your questions about very long exposure photography and motivates you to give it a try. I’m sure that you will love the results and the experience!

bonjour,je prend une photo,et l arrivée j obtient une photo tres noir,rien

Thank you for the excellent, and helpful, article.

I am wondering why the sensor would heat up during long exposures than it would while recording a video of several minutes in length. Does anyone have any insight into why this would be the case?

Thank you!

Great article, Elizabeth.

I have been planning on doing some “really” long exposure photos and your article has been a real “eye opener” and I can now apply your tips and techniques the next time I take my camera out.

Thanks for the spectacular article!

Thanks so much Joshua! Have fun, but be warned, long exposures can be addicting!

Hi Elizabeth, Thanks for a wonderful article, i am new to Long exposure photography. I have a very basic question, with my Nikon D750, i have set the manual mode, with aperture f/11 and shutter speed of 1s, with B+W 6 stop(1.8) ND filter, i should have got 1 min shutter speed, but looks like i just get 1s. What may be wrong. i tried with and with out UV filter below the ND filter, but result was same.

Forgot to mention that I am using a regular camera remote.

Hi Mahesh, did you meter the scene before you put on the 6 stop filter? That is what I am guessing happened. I would expect a “typical” daylight exposure (with no ND filters) to have a shutter speed of around 1/60s at f/11. Thus, if you are only using a 6 stop filter your adjusted speed would be 1s . From 1/60 to 1/30 to 1/15 to 1/8 to 1/4 to 1/2 to 1s is six stops. So, to get a longer speed of 1 min, you will need either a higher stop nd filter, or a cloudier, darker day!

Thanks for your comment and question. Let me know if this makes sense!

Thanks Elizabeth, will try out on a darker day.

Wonderful article. What a teacher Elizabeth is!!!!

My next project. I might have to practice my self defence or bring an attorney because the local ordinance inspectors at Bondi beach make Hitler’s brown shirts seem positively benign

I photographed a waterfall last year and got a purple patch, exactly like the one in your lighthouse picture. I was perplexed as to what it was at the time, and thought at first it might have been a lens issue, reflection etc, but never a light leak. Now I know exactly what the problem was and how to fix it! Thanks so much for the great article!

Glad I could help Arron! Fixing a light leak is east once you know what it is!

Thank you so much for this great article Elizabeth! :-)

Your welcome Oliver! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

As a complete novice, I have a question concerning some data that appears below each of the images, for example NIKON D700 + 24mm f/2.8 @ 24mm, ISO 100, 121/1, f/8.0

Whilst I am familiar with most of it, I have never before seen what in this instance was the 121/1 details – is it to do with the Shutter Speed, as up until now, I have only seen that represented as follows:-

1/250 or 1/1200 etc., for example

Thank you

Hi Mike,

You have it right! 121/1 is describing the shutter speed in seconds. Because these shutter speeds are all over 1 second, they get recorded as a fraction over 1. Most photographs are taken at very fast shutter speeds, so fractions like 1/250 are more common. All of these shots were taken with much longer exposures, and as such are recorded as whole seconds. Hope that helps.

Elizabeth,

Many thanks – in other words 2 minute 1 second exposure.

Regards.

Mike

You’ve got it right Mike!

Elizabeth, I don’t know if this was already asked but have you had any luck using Live View. I just screwed a Hoya 10X ND on my D7200 with 17-70, put a piece of black gaffers tape over the OVF, and the camera seemed to focus and take a properly exposed, long exposure image. Was I just lucky this one time or is this a lazy way of taking long exposures under 30 seconds?

Hi Mike,

I’m not familiar with a Hoya 10X. Could it be a Hoya X8? If it is, this is filter only causes a three stop reduction in the light. With this filter, you will be able to see through it. Your camera should also be able to meter through it, which would be why you could see using live view. A three stop filter is great for slowing shutter speeds enough to take 10-30 second exposures, but won’t let you take 10-15 minute exposures. If you hold the filter up to the light, and you can see through it, then it is likely that your camera can meter through it and that you will be able to focus and compose with it on. Hoya has a NDX400, which is much darker. It will cause a nine-stop reduction in the light. With this filter, you would not be able to focus or meter if it is on your lens. Because different manufacturers use different methods to describe the strength of their filters, it can be very confusing.

Let me know if this explanation makes sense!

If despite using ND filters doesn’t give the silkiness one requires, stopping down to f/22 may work. Apart from image softness due to diffraction, it creates 2 additional problems:

– dust spots

– hot pixels

which will need cleaning up in post.