Even though it’s been about 15 years, I still see it as if it were today: For the first time, I’m standing in a South American cloud forest with a camera and a 300mm zoom lens. Suddenly, from a nearby thicket, I hear the familiar chirp of a Masked Flowerpiercer. A handful of blue feathers appear in a tangle of dense branches. I raise the camera to my eye, aim, and press the shutter. I got it! Or did I? Well, the bird is in the frame, but it’s just a small number of blurry, blue pixels. My newfound passion for wildlife photography is quickly replaced by the sobering realization that I have a long and thorny road ahead of me if I want to make my wildlife photos better.

My ambitions as a beginning photographer were not all that grand – my only goal was to make the bird in the picture large enough and easily recognizable. Achieving this goal has become easier as I have gained experience in the field and improved my equipment. With a long telephoto lens and a little know-how, it is not such a difficult thing to have the animal fill the viewfinder.

Then the challenge becomes something more. Don’t get me wrong, a lovely bird on a nice stick with a pleasant background is certainly not bad. I’m always happy to take such a picture, especially if it’s a species I haven’t photographed before. However, after a while, you want to push the envelope even further. In order not to stagnate as a photographer, you will try to find new approaches, to capture the subject in a different way, and to come up with a new, or at least less hackneyed, solution.

Often, this will result in a photo that simply doesn’t happen or doesn’t turn out as expected. Sometimes I plan these shots carefully, and sometimes they are just a result of chance. It makes me all the happier when the photo turns out well. The purpose of this article is to reflect on ways that you can approach wildlife photography a little differently and help it stand out from the crowd.

Table of Contents

1. Humor in Photography

I recently published an article discussing the value of humor in wildlife photography, and it struck a nerve. It was one of the most viewed articles that Photography Life this year with over 100,000 views in the first week! Photographers resonate with humorous photos, as evidenced by the number of comedy wildlife photography contests and viral photographs that you’ll see. There is something special to seeing the silly expression or pose of an animal, even if we are merely projecting our own feelings onto them (the kangaroo below wasn’t really waving at me, but it felt that way)!

Capturing humor in wildlife photography means that your viewer will connect with your photo. It’s not something that you can usually predict. You need to simply be aware of the potential for humorous wildlife photos any time that you’re photographing an animal. You never know exactly what they might do or how long their attitude may last. Be prepared!

2. Interesting Behavior

It’s almost always more interesting when something is happening in the photo. Photos that tell a story are more appealing than descriptive, static images. Most animal activity involves searching for food, courtship, caring for offspring, or moving from place to place. Study what to expect from a particular species and when is the best time of year to see certain behaviors. Then there’s nothing to do but search and wait.

I could watch the courtship of the Andean cock-of-the-rock a hundred times and still be entertained. However, photographing this show is a real challenge! Why is that? Look at the EXIF of the image below. Due to poor lighting conditions, most of my photos of these iconic Andean birds are static. Here, however, I was able to capture the characteristic movement while keeping the head in focus.

The following photo of a tropical spider of the genus Nephila reveals two interesting facts about its biology. For starters, you can see the last moments of a cicada’s life as it is captured by a female Nephila. Now look a little higher. The smaller spider above is not a cute baby Nephila, but actually the father of the family. Judging by the size difference, it’s clear who has the upper hand in any potential relationship disputes.

Below is another example of interesting behavior. The Common Toad has venom glands. But what good is that when the grass snake has built up a reliable defense against its venom over millions of years of their coexistence? The toad has no choice but to rely on the predator’s common sense that such a large meal cannot be swallowed. On rare occasions, it stands up large and makes itself look too big to eat when a predator approaches. Apparently, this strategy works, and the toad lives to fight another day.

Show me your legs and I’ll tell you if you have a chance with me. Well, at least that’s how the Blue-footed Booby’s courtship process works. This seemingly pointless requirement is not just due to sheer vanity. In fact, nothing says more about a potential father’s parenting skills than the shade of blue on his legs. Bright blue indicates excellent health and good nutrition; dull legs, on the other hand, betray a bird whose hunting skills and health are not as promising.

Finally, I like the behavior captured in the following image. Apparently you don’t need to be able to work miracles to be able to walk on water – sometimes, it is enough to have sufficiently long toes and a light body weight, like the Comb-crested Jacana from Australia. Perhaps even more interesting is the family life of these birds. A female will defend her territory inhabited by a number of males, who will only mate with her. In turn, the males run the Jacana family – not the female, unlike with most birds.

3. Unconventional Compositions

A well-posed subject, a visible face, plenty of space around the subject, and a well-balanced composition. All of these are great ways to take stronger wildlife photos, but why not break the rules once in a while? The following photos have one thing in common: Their composition is at best unusual, and some might even say strange. Let’s take a look at them.

We’ll start with photographing a bird from behind! Not to mention in such a way that you can’t even see its head. Besides, everyone knows that the central composition is the most boring thing in the world. Despite that, this photo won the Czech Nature Photo contest in the bird category. Well, not exactly this one, but a photo of the same moment taken by my colleague and friend Tomas Grim.

Another photo of a bird without a head and almost without wings. It probably wouldn’t stand on its own, but it makes a good addition to a photo story about the pirates of the sky – Great Skuas. These birds are excellent and devoted parents. They become fierce defenders of their territory as they care for their young. This was the last photo I took before taking a hard blow to the lens.

In the following case, I focused on the graceful curve and the red eye of this beautiful bird. Not many would recognize in this semi-abstract photo one of the greatest pigeons of our time – the Crowned Pigeon of New Guinea.

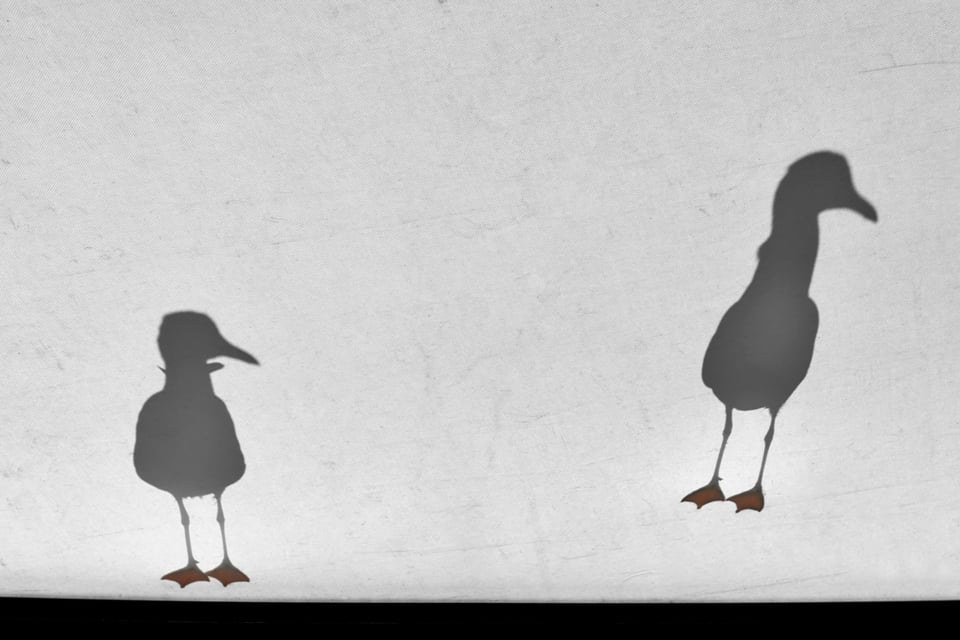

Finally, this photograph of two seagulls is reminiscent of a traditional Chinese shadow puppet theater. There is nothing particularly unusual about the spatial arrangement of the two actors. But what is surprising is that none of the birds are actually visible. We can only guess their shape and figure out the true nature of the photo after staring at it for a while. The simplicity of form and color gives the photograph its inner charge.

4. Animals and Environment

It is not necessary, or even desirable, that an animal always fills the entire image area. Of course, if you want to show what the animal looks like, it’s fine to show every single hair, feather, or scale in the photo. But if you want to tell more about the animal, I suggest you include a shot of it in its natural habitat as part of your story. Note that filmmakers use similar principles. From the establishing shot to the close-up.

This Chocó Toucan fully understood my creative intent and perched on a perfect branch about 50 meters from my camera. Although I took the photo with a 500mm telephoto lens, it shows a lot of the environment these birds inhabit – the densely vegetated montane cloud forests of the western Ecuadorian Andes.

How could you take a photo of a camel without the desert? Capturing this attractive but inhospitable environment, along with its typical inhabitants, was my goal when I visited the desert near Dubai. Early in the morning, I was dropped off deep in the desert to spend a full day among the dunes. I was happy when, after a few hours of walking, I came across this group of camels and spent several hours photographing them.

Next up, the Australian Blue-winged Kookaburra differs in many ways from the classic kingfishers of the genus Alcedo. Perhaps that’s why they were given a genus name that uses the same letters but in a completely different order – Dacelo. Unlike the European solitary kingfishers, the kookaburra is a cooperative breeder that benefits from living in groups. Rather than the fish-based diet of most kingfishers, it usually is found far from rivers or lakes. The photo below shows its typical habit of a savanna woodland.

Finally, I took this photo of the Little Egret in the center of one of the world’s oldest metropolises, Rome. After taking several close-up shots of other birds, I saw this Little Egret on the opposite side of the millennia-old Tiber River. I came up with the idea of giving the egret less space in the frame and letting the dynamic curves of the river stand out, reflecting the surrounding buildings in the setting sun. I let the river flow across the sensor for 1/10 of a second to introduce a little blur and tell something about the environment.

5. Wide Angle Shots

There are many advantages to photographing animals with a wide angle lens. The most important is that you can combine two useful techniques: letting the animal fill the frame, and showing off the background environment. In addition, the wide-angle lens contributes to a more intimate image. After all, you often have to literally crawl on your elbows and knees to get these shots. Plus, you only need a small and relatively inexpensive lens. The fact that you’ll rarely get more than a couple of these photos per expedition is also an advantage – there is no need to sort through thousands of technically perfect telephoto shots. As I said, all advantages.

Youthful animals are curious. This young Carunculated Caracara wanted to find out what made me, an exotic-looking bipedal hominid, crawl on all fours. Could I be eaten after all? Thanks to the trusting nature of these birds and the curiosity of youth, I was able to squeeze both the bird and the base of Ecuador’s Cotopaxi volcano (5,897m) into this wide-angle shot.

A wide-angle lens is great in that it can draw the viewer into the animal’s environment. However, when photographing, keep in mind that animals often appear to be further away in the viewfinder than they actually are. That was the case of this Nile Crocodile. I was very surprised when it splashed into the water about a meter away from me after this jump. A little close for comfort and not a shot I intend to repeat!

With some animals, you may even need a wide angle lens just to get them completely in the viewfinder. This Amethyst Python was resting peacefully on the forest floor, not at all disturbed by my presence. It was well aware that it was the largest predator in this patch of forest, and I couldn’t change that with my camera.

Lately, I’ve been making extensive use of the Auto Capture feature that the Nikon Z9 got about a year ago and the Z8 about a year after that. This feature allows you to eliminate what is undoubtedly the biggest obstacle to wide angle wildlife photography – the photographer. Once you find a spot where you expect to see an animal, just set up your camera and let it do the work. That’s how I took this photo of a White-throated Dipper. Don’t have a Z8 or Z9? No problem, many cameras today can be controlled remotely from your phone, tablet or computer.

Of course, to take photos this way, you need to encounter animals that are very tolerant of the presence of a human, or at least a camera. Hummingbirds clearly fall into this group. Especially those that are used to visiting feeders. Although the following shot of the iconic Sword-billed Hummingbird was also taken using the Auto Capture feature, I’m sure with a little patience I could have taken it with a camera in hand. The background is the cloud forest of the western Andes at about 3,000m.

6. Conclusion

With today’s article, I had two main goals. The first, zoological, was to introduce you to some interesting animals. The second, photographic, could be summed up in a few sentences: Don’t just settle for a descriptive approach to wildlife photography. Instead, try to go deeper beneath the surface. Look for unusual compositions, interesting angles, the behavior of your animal, or even humor. When you do, you will make your wildlife photos even better than before! I wish you good luck, and good light, in this endeavor.

I have a lot of respect for wildlife photography. It cost a lot of money, time, and effort. I think my favorite here is of the Victoria Crowned-Pigeon!

It’s true it’s a lot of effort but the time and effort spent out in the wild is the best part!

Excellent article, Libor and beautiful shots. Very creative! I think all of this article sort of hints at an underlying thing regarding wildlife photography, that at least is true for me personally: I often don’t realize that compositions are extra interesting to me simply because they are of unusual or rare birds, but that others may not see them in exactly the same way since they may not be as familiar with birds. Thus, compositons illustrating birds in new ways or unusual ways or way that show their behavior are extra appealing. I’m frequently surprised when I show my photos to others and they pick their favourites for a reason I would not have guessed. In other words, I sometimes give extra weight to certain shots because they are of rare birds or birds with some interesting biology or habitat but most others don’t see it that way, I think.

I think your article gives some of these non-obvious (to me) explanations. And exploring these styles can also give the photographer a new way of seeing the same old subject — through the mind of others, which is also an interesting activity.

Thanks Jason for your comment. My experience is exactly the same as yours. Give normal people, I mean non birders, to pick their favorite photos from your portfolio and you rarely agree on the same candidates. Because only the author sees meanings behind the photos that others miss (the rarity of the bird, its interesting biology) or simply cannot know and appreciate (the difficulty and hardship of taking the photo). Sometimes I think the photo should speak for itself, but more often I feel that without the caption the photo is incomplete. After all, photo captions are a big topic. Of course, I can see a portrait or a nude without text, but nature photos often need that descriptive crutch as well.

I guess the question then is, how much should a photographer shoot to inspire others and how much should they shoot based on their own tastes? And is there a good middle ground of representing your own style and experiences versus making those experiences more understandable to the viewer?

These photos are all about access which many people can not afford to travel to all the locations these were taken. You should be trying to show interesting photos of common animals like sparrows, red-wing black birds, woodpeckers, foxes etc… The article should be about how to make photos of common animals interesting, not just exotic ones many will never have the chance to photograph.

“Common” or not depends a lot on where you live. I guess this website has a fair number of visitors from all over the world, including places where many of these animals are common. But even for those living in the most boring parts of Europe or the US, toads, dippers, seagulls, and egrets are not exactly the most exotic of specimens.

I have kookaburra that visit my house every week or so, if i go to the beach i can see seagulls and if i hike in the hills behind where i live kangaroos. Eu Toads, dippers and egrets are exotic.

Or maybe it’s possible to appreciate a photo even if you can’t photograph the animal yourself. That is the beauty of looking at the photos of others.

Perhaps you should change your screen name. There is not much pro about what you said. Why should anybody tell someone else what to photograph, especially when they are writing for a high end blog like this one? People have written about exotic animals and places for years here, and we are all better off for it. That is kind of the point of Photography Life, after all – to learn from others.

While I wouldn’t have expressed the point quite like this, I do have reservations about wildlife (and landscape) photographers who travel the world, often, perhaps usually, by air, when their very subject-matter is dependent on the quality of the environment they wish to photograph. That is not helped by airline CO2 emissions and the failure of governments, in the face of industry lobbying, to tax airline fuel.

Air journeys are mostly by a particular group, who can afford to pay the tax:

ourworldindata.org/break…2-aviation

I agree with Jason’s sentiments. Perhaps however I would suggest a gloss that the beauty lies in seeking to view the images of local photographers, especially in low income counties.

Of course, one then hits the argument that tourism income in those places can create jobs, especially for those who are engaged to protect wildlife.

Nothing in considering best policies for the environment is easy. But I believe that this is a legitimate debate and that photographers should not be seeking to close it down.

This is definitely an interesting topic and cannot be seen in black and white. The environmental impact of air travel is undeniable, but on the other hand, the rate of nature degradation in places without tourists/photographers would be even faster in many countries. As I have illustrated several times with the example of Madagascar. Unfortunately, its nature would be destroyed by environmental destruction long before the climate crisis caused by excessive CO2 production. Sometimes I ask myself how I, as a photographer, can give something back to nature. Besides spending my money locally, I try to publish my images, write articles and give lectures. I try to be a kind of ambassador for nature. Also for the locals who often have no idea what fascinating animals live around their houses.

That’s a very interesting comment. The choice of the subject and the sort of attractiveness of the species obviously plays an important role, but how it is perceived by viewers from different parts of the world is very varied. We usually think of an exotic animal as one that doesn’t live in the nearest meadow or forest. But this is perceived differently by a photographer from South America, Africa, or even Central Europe, as in my case. However, I have included in my selection a few photos that I took close to home. So from the point of view of a North American, these are indeed very exotic animals (like White-throated Dipper, Common Toad), but from the perspective of a European, they are quite common. Where the species is photographed also plays an important role. White-throated Dipper in Europe? Well, quite nice. The same species in America? That would be in a whole different league. However, I didn’t choose by species when selecting photos for the article. I was looking for photos that would best illustrate the idea I wanted to express.

Artykuł dowodem na to, że każdym obiektywem można zrobić świetne zdjęcia zwierząt. Zdjęcie gołębia nikonem D70 i 50mm są świetne.

You’re absolutely right. You can take great photos with almost any camera these days. It’s just that some cameras make it easier. The 50mm used to be my longest “telephoto” lens. That was when my camera and all my equipment were stolen when I was traveling. You have to work with what you have. And sometimes that is a valuable lesson.

I forgot to mention all the photos are beautiful, but the last two are outstanding. They are putting together beautiful animals, the environment in which they live, a deep knowledge of their behavior, and technical skills up to the task.

Great work!

Thank you, Massimo. I’ve been thinking about taking these photos for a while. However, I feel it could have been done better. Maybe next time. By the way, it would be great to go into the field together, what do you think? Let’s think of a project together.

What a great list of tips for improving photography!

Thank you so much for all these details! It reminds me exactly of the different categories in the “Wildlife photographer of the year” competition.

I love the photo of the webbed feet on the tarpaulin or fabric!

Thank you, Adrien. The photo of the seagulls on the canvas roof of the restaurant in Melbourne reminded me that photographing animals can be a very comfortable thing. A cold beer on the table and a camera in my hand, paradise indeed.

Very well done!

Thank you, Scott.

Great photos, Libor! Glad that crocodile decided to look for a snack elsewhere though!

I was also very pleased with his dietary decision :-)

The blue-footed booby in your photo lives up to its name. Of all your comical photos, this one caps them all. Your opportunities for shooting rare and unusual creatures is enviable, Libor. And yet, I have a photo of a local seagull that is almost identical to your picture of the Great Skua’s feet. I sometimes think that we share certain perspectives in selecting what to shoot. As always, your pictures are beautiful and enjoyable to look at. Your love for the wild things comes through. Perhaps that love is the key element in photographing the world around us. For me, the most beautiful photos are never planned. You see them afterwards in post processing, and you realize that was when the magic moment happened.

Thank you, Elaine. You’re right that one should love what one photographs. Just last week my wife and I were walking along the river and a White-throated Dipper flew by just a few meters from us. The twinkle in my eye and the love with which I said its name made my wife amused and a little jealous. Like you, I often reveal my best shots when I’m sorting through them in my camera at the end of the day. More and more, though, I can sense when I hit a golden vein in the field. That’s when I resemble a hummingbird that has just found a flower full of nectar.