Caves are some of the most challenging places on earth to explore – and if exploration alone is so tricky, you can imagine how difficult it can be to photograph them. I recently made a trip to Belum Caves in the state of Andhra Pradesh in India. I struggled to capture them for the first two days. But as time went by, I started getting more satisfactory results and learned how rewarding they could be.

I am a firm believer that you don’t get a good photograph of a scene unless you enjoy it in the first place. So, this article will go into more than just how to photograph caves, but also how to enjoy them.

Table of Contents

Appreciating Caves

I reached the entry gates of the Belum cave system at 9 AM on a Saturday. I wanted to be the first person to enter to avoid the crowd.

My first day of the visit was a “recce,” or what most of us call a scouting trip. Belum is an elaborate labyrinth of caves that spans 3 kilometers, and I wanted to slowly understand the opportunities for photography instead of rushing in. It was only the second day that I headed back with all my gear prepared.

In total, I spent four days at Belum Caves and explored every channel. Even then, I would have been happy with a few more days in hand.

Cave photography isn’t for everyone. It certainly isn’t a good environment for smartphone snapshots or Instagram selfies (and I saw plenty of people try and fail to get such photos in the harsh, metal halide light.) But if you have the patience and preparation to accept the challenges they throw at you, caves can be highly rewarding to admire and photograph.

Challenges

Below are some of the challenges of visiting caves, let alone photographing them:

- As you go deeper inside a cave, the humidity and, in most cases, the temperature keeps increasing. You’ll probably sweat enough to drench your shirts. You can also expect to consume about 3-5 times the amount of water you’d typically need outside the cave. Make sure to also bring some food or drink that can replenish your salts and electrolytes.

- Most caves are wet, especially the narrow ones. Go with suitable footwear.

- Caves are abodes of bats. Bats reside in numbers of hundreds or, in most cases, thousands. So be prepared to be in the smell and walk over bat droppings. A good medical-grade mask can be helpful in some caves to avoid breathing in too much dust.

- If you are even a bit claustrophobic, caves can exacerbate the problem. Don’t stray too far from an entrance if this is a concern.

- You need at least one headlamp. Some of the famous caves will have lighting in most places. But it is always advisable to have a headlamp.

Once you understand those challenges and prepare for them, you can focus your energy on getting good photos!

Stalactites

Some of the most rewarding features of a cave system are the mineral formations. These formations are prevalent in erosion caves – AKA, caves formed by flowing water.

What causes mineral formations to appear? Commonly it’s due to rainwater. Rainwater tends to be mildly acidic, and as it naturally flows from the outside world into the ceiling of the cave, it dissolves some of the calcium-based minerals on the surface of the cave.

The droplets of calcium-rich water trickle down slowly, and they leave a small trail of the sediment behind. It’s similar to what happens when hard, alkaline water trickles down a leaking tap.

Over the years (or millennia), these small trails of sediment form beautiful ceiling art that we call stalactites.

The older the cave, the more pronounced the formations tend to be. It also depends on the mineral content and amount of water that reaches the particular cave.

Stalagmites

Stalagmites are another major formation found in most caves. They’re made of the same material as stalactites, but they differ because they form on the ground rather than the ceiling. Stalagmites form when water flows over a particular area of the cave, or when it drips down from stalactites.

Now that we have a basic understanding of caves, let’s go through what you need to know in order to photograph them.

Gear recommendations

Tripod

A sturdy tripod is first item on the list for cave photography because we deal with extremely low light inside caves. Most of the time, you’ll be at multi-second shutter speeds and need all the help a tripod can offer.

My recommendation for a tripod is to use one with the highest max height and lowest minimum height. The perspective of objects in a cave can change dramatically as you change tripod height, especially in smaller caves. You may want to be at “eye level” with stalactites to avoid perspective distortion, or at ground level pointed upward to emphasize the sheer size of certain formations.

There’s also a chance that you’ll need to bracket images for an HDR or focus stack in order to get the photo you want. In either case, a tripod is necessary.

One bit of good news is that there is usually not much wind or movement in a cave system, so you don’t have to worry about external sources of vibration on your tripod (unless you put one of the legs in a flowing stream). As long as you use a remote shutter release and the electronic shutter, you can extend the tripod as much as you want – even the center column – and still get tack-sharp photos.

Lens Recommendations

For the entire Belum caves trip, I used only the Nikkor 20mm f/1.8G prime. Without a doubt, a wide angle lens is the way to go in most cave systems. Anything wider than 28mm (full frame equivalent) is ideal.

If you’re using a tripod, the maximum aperture may not be critical, but a lens with f/1.8 or f/2.8 can still make it easier to focus and compose compared to a slow f/5.6 zoom. Wide apertures also let you get a shallow depth of field and highlight individual formations. So, I recommend an f/2.8 lens or wider if possible.

Camera Recommendations

Contrary to what some photographers may think, you’ll usually be photographing a cave at base ISO so long as you’re using a tripod. And because of the difficult lighting conditions in a lot of cave systems, dynamic range is an important factor. So, a full-frame camera with good dynamic range is ideal, but a smaller sensor aps-c or micro four thirds camera isn’t a dealbreaker.

If you do plan to shoot handheld, though – since not all cave systems allow tripods – you’ll definitely want a camera with the best possible high ISO performance. And ideally combine it with an f/1.8 or f/1.4 lens.

External Light Source

Caves are some of the darkest environments on Earth, and many of them don’t have any lighting installed, so you’ll need to bring your own sources of illumination. Other, more famous caves may have lights installed already – but these can be more annoying than helpful.

If the authorities were sensible enough to use uniformly colored light sources, it would be a lot better. But often, you’ll end up with conflicting lighting as shown below:

In addition to creating disco-like effects, these high-intensity lights tend to produce blown-out highlights as well as shadows with almost completely lost details.

Even in caves like this, you’ll usually be able to find areas without terrible artificial lighting, which is why it’s important to bring light sources of your own. I recommend at least two or three external light sources with similar color temperature. I’ll cover this a bit more later in the article, but anything from headlamps to remote-triggered flashes could work.

Photographing Caves

Now that you’re prepared with the gear above, let’s go through the process of photographing caves.

Caves are generally comprised of hallways, narrow passages, pools/rivers of water, and mineral formations (stalactites and stalagmites). Instead of giving you a list of tips and tricks, I’ll instead explain how I recommend shooting each of those sorts of subjects.

Photographing Hallways and Large Chambers

Generally, though not always, the entrance to caves are wide crevasses that tapper as we go deeper. The photo below is one such example, so let me take you through the step-by-step process of how I captured it.

- Using a tripod, I set my camera to base ISO (100 in my case) and stopped the aperture to f/5.6 to get good sharpness across the frame (since f/5.6 is the sharpest aperture on my lens). Granted, f/5.6 isn’t quite enough depth of field here, but I’ll get back to that in a moment. Matrix metering recommended a shutter speed of 8 seconds.

- I positioned the tripod at a height of about one foot, emphasizing the pathway that led up the cave. I wanted to give the perspective of taking an observer into the cave.

- In order to get enough depth of field, I decided to focus stack four images in post-production. I first focused on the brick pathway at the foreground, then halfway down the pathway, then just in front of the light, and finally on the wall in the background. It was just barely bright enough that I could autofocus each time, but I easily could have focused by shining a flashlight if needed.

- When I took each photo, I made sure not to jolt the camera during the long exposure. I also used a remote shutter release and electronic front-curtain shutter to avoid causing camera shake.

- Back at my computer, I used Photoshop’s Auto-Blend Layers option to focus stack the images. The process is pretty simple:

- Import all the source images as layers in a single Photoshop document.

- If the images have any misalignment, select all the layers and go to the menu option Edit >Auto-Align layers. This will eliminate the mismatch in composition, if any.

- Highlight all the layers and go to Edit > Auto-Blend Layers. Select “Stack Images.” I also recommend keeping the two other options – “Seamless tones and colors” and “Content-aware fill transparent areas” selected.

- On this particular photo, I then converted the photo to black and white. Low-key monochrome images are some of my favorites, and the contrast here works great in black and white.

- I then did some remaining curves adjustments to adjust the contrast and bring out the details I wanted. Done!

Photographing Tight Crevasses

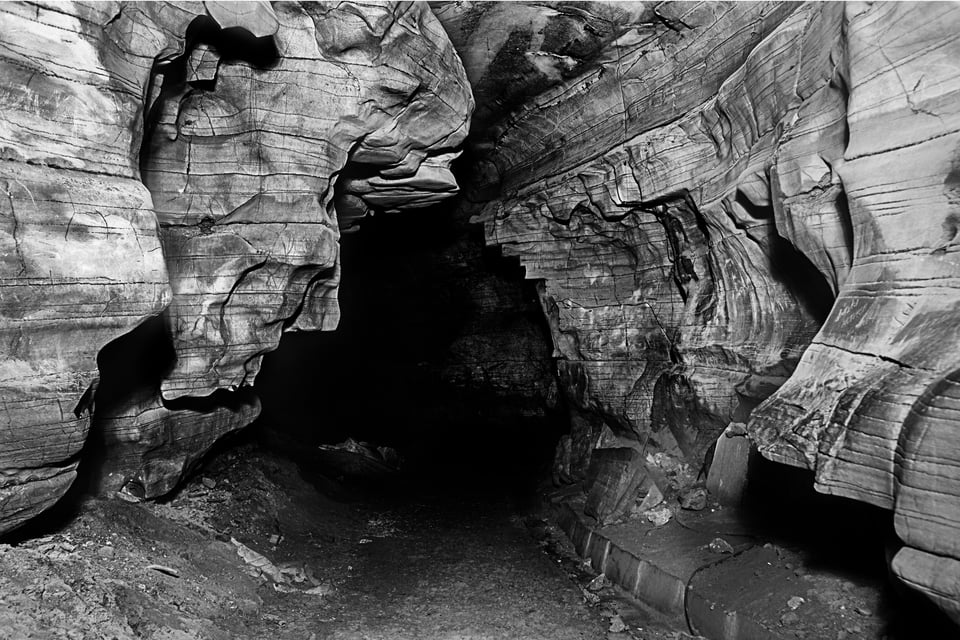

As we venture to the deeper parts of caves, they generally branch out and tighten. For example, take a look at the image below:

This is when the power of ultra-wide lenses is especially clear. A longer lens would simply eliminate too much context in a lot of cases. Here, a 20mm prime did the trick for me.

I lit the image above by light painting during a 30 second exposure. Light painting is when you use a low-intensity light to illuminate portions of the scene during a long exposure. It’s common in landscape photography at night, but the dark environment of caves is equally suited to light painting.

Here, I primarily painted the formations that were close to the camera. I did this in order to create a “fade” effect and sense of distance progressing into the background. And I made sure to point the light from a slight angle in order to create interesting shadows.

You need to move the source of light at a pretty constant speed as you shine it on your subject, or you’ll end up casting harsh highlights on some areas more than others. Light painting usually takes a few tries to get right, but it’s very rewarding when you do.

Here’s one more example of photographing a narrow cave passage:

This time, I deliberately left parts of the photo darker by lighting up only the most interesting formations. The result has a bit of a “natural vignette” and guides the viewer’s eye through the photo how I want. Here, I lit the image by placing a cellphone in the middle ground and a flashlight out of frame in the background. And, as before, I converted the image to black and white in order to emphasize the amazing shapes and forms of the cave.

Photographing Stalactites and Stalagmites

As I mentioned earlier in the article, stalactites and stalagmites are some of the most interesting attractions in a cave. But they’re not always easy to photograph. Take a look at the picture below, which I don’t think works very well:

This is the view I got with a 20mm lens mounted as high as possible on the tripod and filling the frame with a stalactite. It could make a good documentary picture, but it lacks a story and isn’t a very interesting artistic photo.

That goes to show something important about cave photography: You still need to tell a story, just like in outdoor landscape photography. Rather than capturing a “documentary” angle of a single subject, how about showing it in context to the rest of the scene? Compare the image above to the one below:

To me, this one tells a better story. Here’s how I captured it:

- I envisioned the image and realized my 20mm lens wasn’t wide enough to capture it in a single shot. So, I planned to take a panorama, starting with my camera mounted in landscape orientation (horizontally).

- Panoramas don’t always blend well with ultra-wide lenses, so it’s best to leave excess room in case you need to crop a lot later. Here, the splashes of water at the bottom of the photo are very important to my composition, so my first photo in the panorama pointed mostly below them, just to be safe.

- The next shot was taken by tilting the camera vertically. I made sure there was at least a 30% overlap between the two images.

- I took four more shots, each time composing a bit higher until I had plenty of space above the stalactite at the top.

- At home, I used Photoshop’s Photomerge option to stitch them together. Because I had included extra room on the top and bottom of my frame, it was easy to crop the composition I wanted without losing any vital component of the composition.

Conclusion

In this article, I’ve tried to give you all the information you need in order to appreciate and photograph caves while staying safe.

Maybe you’ve wondered why so many photos in this article are black and white. There are several reasons, but one of them is that the usual pale colors in a cave (and the unusual artificial light) are often distractions that don’t add much to the meaning of a photo. At least for me, the amazing contrasts and shapes in a cave translate better to black and white. I also love black and white in the first place, so it’s a good excuse for me to use it.

If you have any questions about this article or want to add any more pointers, please feel free to do so in the comments section below. Happy caving, and happy clicking!

çok teşekkür ederim.

In Canada most caves are between 13.3-14.4C so you need a light sweater, long pants and wool socks. There is no wind in a cave so a cool 56-58F is very comfortable for hiking. Cave temperatures tend to be whatever the average daily temperature of the caves location is,

just a tip for good planning. Thanks, nice article.

ఫోటోలు బాగున్నాయి. చక్కని వ్యాసం. బాగా రాశారు..

In most caves I have been to, the use of a tripod is banned, especially when there is a guide involved. Therefore an off camera flash is the only way to go. Nice article though.

Yes. Most show caves I’ve seen ban tripod photography. The reason to ban on tours is obvious, but they’ll ban on self-guided sections as well, as the paths are typically too narrow for visitors to pass a tripod. Some operators will ban tripods, just because. I’ve gotten permission exactly once, when on an assigned shoot and the cave was privately owned.

Changing the subject: when I was a lad I once saw a photographer mount his camera on a tripod in Carlsbad Caverns, then illuminated the shot by shining a flashlight all over his subject. I’ve always wondered how that turned out.

I wonder how they would feel about something like a platypod.

I think this is a nice article on a very different topic, with great illustrating photos. I’ve crawled through wild caves, and I love photography, but I’ve never combined them. I may try, though I’m tempted to try a fisheye, distortions be damned.

…and I’d add, great to see an article that isn’t Nikon specific on photographyNikon.com.

Christopher. May I ask which is the problem with photographynikon.com? What they says in tutorial articles can be implemented with any camera. If they liked nikon I see no problem with it. By the way if you read lens recomendation for caves author uses a nikon 20mm f1.8

Nestor,

I have nothing against Nikon equipment, and it’s certainly appropriate for authors to discuss lens length and speed. If you look at the last dozen articles, though, most of the articles about Nikon equipment per se, not subjects or techniques. Lots of sites talk about gear. Fewer talk about photography. I am sad to see this site emphasizing gear so much now, it wasn’t always so.

I agree. While I shoot Nikon, it gets on my nerves when other sites focus on Canon or “Evil” Sony. ;-)