On DSLR cameras, sometimes lenses don’t focus exactly where they should because of the way a DSLR works. Moreover, various factors such as manufacturer defects, sample variation, insufficient quality assurance testing/tuning and improper shipping and handling can all negatively impact autofocus precision.In such cases, you may need to calibrate your lenses or fine-tune their autofocus performance to compensate for this discrepancy.

A lot of photographers get frustrated after spending thousands of dollars on camera equipment and not being able to get anything in focus, but this article will provide some simple tips to solve that problem. If you are wondering about how to calibrate lenses, this article will tell you what you need to know!

Table of Contents

1) Why Calibrate?

Why is there a need to calibrate lenses? Due to the nature of the phase detect autofocus system that is present on all SLR cameras, both cameras and lenses must be properly calibrated by manufacturers in order to yield sharp images.

This problem is even more noticeable on high-resolution cameras. A slight focus issue might not be as noticeable on a 10-12 MP sensor, but will be much more noticeable on a 25+ MP sensor (assuming both sensors are of the same size).

While landscape and architectural photographers might not care about focus issues (since they photograph at very small apertures that hide small focus issues), portrait, event and wildlife photographers are typically much more worried about focusing problems.

I personally like to photograph people wide open with my lenses, which can be a challenge for obtaining perfect focus on my subjects. How frustrated would you be, if you focus on someone’s eye and you get their nose or ears in focus instead? I am sure you would not want to have such problems, which is why I encourage you to test your gear and fine tune it for optimal results.

2) Camera vs Lens Calibration

Lens calibration uses a specific camera setting that allows fine tuning autofocus operation of lenses, which means that we will not be changing anything on the actual lens. However, some manufacturers such as Tamron have provided USB docks for their lenses that allow more refined focus calibration. If you own such a lens and the methods in this article don’t work, I suggest consulting the manual of your lens to see if it has such a feature.

On the other hand, manufacturers can also physically recalibrate a lens if it focuses very badly. Physical calibration of lenses should only be performed by manufacturers, since lenses have to be disassembled, tuned and reassembled. I would never recommend to try doing this yourself at home, unless you really know what you are doing and you are OK with voiding the warranty and potentially damaging your lens.

3) How Calibration Works

As I pointed out in the phase detection autofocus system and how to test your DSLR for autofocus issues articles, the source of autofocus problems could be an improperly calibrated camera, a lens or both. The procedure highlighted below can potentially address all three scenarios, depending on how badly misaligned the whole setup is.

Calibration works through a setting in your camera, which allows compensating for either back-focus (when focus is shifted behind the focused area) or front-focus (when focus is shifted in front of the focused area). This compensation can be performed in small incremental steps (typically from 0 to -20 and +20 in steps of 1), which allows for precise fine tuning of the autofocus system.

Negative numbers compensate for back focus, while positive numbers compensate for front focus problems. To put it differently, dialing a negative “-” number will move the focused point closer to the camera, while dialing a positive “+” number will move the focused point away from the camera.

So what happens when you dial -5, for example? The camera tells the lens something like this: “aim at where you would normally focus, except slightly move the focused point closer to the camera”. In essence, this would be needed when your camera and lens combination constantly back-focuses.

An important fact to keep in mind, is that calibration is camera and lens specific, which means that if you have multiple cameras and lenses, you have to fine tune autofocus on each camera, for each lens you own. In addition, you might need to periodically re-calibrate your camera gear.

4) Calibration Naming Convention

Unfortunately, as you may already know, there is no standard way of naming things in the camera world. It turns out the verbiage for the same thing is different across manufacturers:

- Nikon – AF Fine Tune

- Canon – AF Microadjustment

- Sony – AF Micro Adjustment

- Pentax – AF Adjustment

- Olympus – AF Focus Adjust

So if you are looking for this feature in your camera, keep the above naming conventions in mind.

5) Calibration Feature Availability

The bad news is that this very important calibration feature is often only available on higher-end DSLRs, because manufacturers consider it to be an “advanced” feature. So while cameras like the Nikon D500 and D850 certainly have a fine-tuning option, entry-level cameras like the Nikon D3500 do not.

6) Calibrating Prime vs Zoom Lenses

While I recommend calibrating both prime and zoom lenses, there are a few factors to consider. Most prime lenses, especially above the “standard” range of 50mm have very shallow depth of field at close distances. They are typically my first candidates for calibration, since a slight focus variation is quite noticeable.

Zoom lenses, on the other hand, are typically much more challenging, because there is typically a zoom and aperture range to work with. For example, a superzoom lens like Nikon 28-300mm f/3.5-5.6G VR can go from 28mm to 300mm and its aperture changes from f/3.5 on the short end to f/5.6 on the long end.

Because calibration can only be done for a certain focal length (on some lenses with a severe case of focus shift, I would recommend to even pick a single aperture to fine tune), which focal length would one pick to fine tune?

You would have to either go with a focal length somewhere in the middle of the zoom range, or pick the most commonly used focal length to fine tune. For example, when I fine tune my Nikon 200-400mm f/4G VR lens, I always pick 400mm at f/4 for fine tuning, because that’s the focal length and aperture I use most of the time.

Whereas, for a prime lens like Nikon 85mm f/1.8G, I would fine tune at f/1.8, since that’s the aperture I typically use the most on that lens. More on this below.

7) Calibration Tools

There are a number of free and commercial tools for calibrating lenses. I have tried many different methods and identified the ones that work. A free methods involves printing a bunch of lines on a piece of paper, then setting up your camera at a 45 degree angle and taking pictures.

I started out with this method and quickly found it to be very unreliable. With high resolution cameras like D850, using this method can yield unpredictable results, since fine tuning has to be very precise.

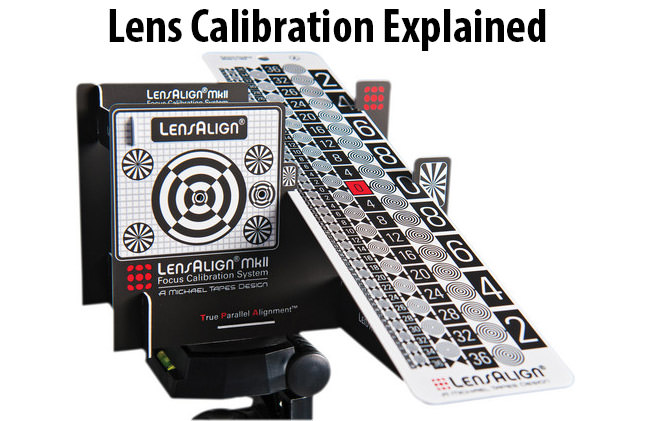

You can also use your monitor screen with a test chart image, which again can be problematic for proper testing. The second method is to get a commercial tool like a lens aligner, which is what I have been doing for the last 3+ years and find it to be much more reliable and precise than the free method.

The third method is to use an automated or semi-automated software calibration tool that can save you time and possibly yield better results. Here is a quick summary with pros and cons of each method:

- DYI Method – Pros: Free, can work if done right. Cons: Precision/accuracy problems, requires a lot of time to setup correctly, does not work well with high-resolution cameras.

- LensAlign or other lens aligning chart – Pros: Works with any camera/lens combination, can be very precise. Cons: Costs money, requires time for manual adjustments and fine tuning.

- Calibration Software – Pros: Automated/semi automated calibration process, high precision, saves time. Cons: Costly and only works well with supported cameras.

8) Calibration Steps

I recommend to take a number of steps for proper and accurate camera calibration. First, you should identify if there is a focus problem. Second, you should try calibrating your camera/lens. The last step is to verify if your calibrated setup works reliably at different distances.

8.1) Identify Focus Problems

If you are an advanced DSLR user, you will typically know right away when there is a focus problem. However, in many cases it is the end-user fault or an issue with camera technique that yields soft images, so I always recommend to use proper ways to identify focus problems.

My recommended approach to identify focus issues is highlighted in my “how to test your DSLR for autofocus issues” article I wrote a while ago. While this approach works quite well, it does not point out if you have front or back focus problems. That’s where a tool like LensAlign or another lens aligning chart can come in handy – you will not only know right away if there is a problem, but you will also determine if the focus problem is related to back-focus or front-focus.

8.2) LensAlign: Manual Calibration

The process of manual lens calibration using LensAlign is pretty straightforward, once you understand what to do and do it a few times:

- You should be in an environment where there is a lot of ambient light, so preferably, do this outdoors in daytime. If that’s not an option, you will have to setup powerful lights to properly expose the LensAlign tool, since a single light bulb in your room will not be sufficient for accurate focus.

- Set up the LensAlign tool on a light stand or a flat surface, then mount your camera on a tripod and properly level it. Thanks to the patented leveling method that Michael Tapes developed, leveling your camera is easy – you just align the red dots on the back of LensAlign with the holes on the front, so that it looks like this:

- Place your camera at a certain distance, depending on the focal length of the lens.

- Set the AF adjustment on your camera to “0” (Setup Menu->AF Fine Tune on Nikon DSLRs) or just turn it off. We will need to start from zero initially and go from there.

- Focus on the circular pattern on the left side of the ruler with your center focus point looking through the viewfinder and take a series of pictures. In between each exposure, you should rack the focus ring, so that everything looks blurry before you start. That way, you force the AF system to reacquire focus each time.

- Do this at least 3 times, then analyze each image on your camera (you can take it to your computer for analysis, but it takes a long time to go back and forth, so I prefer to do it on my camera instead). If you choose to do it on your camera and you have a Nikon DSLR, here is a quick tip – zoom in to 100%, then rotate the rear dial – it will jump from one picture to another, still keeping the zoom level. Here is a sample image that I got with a badly calibrated lens:

As you can see, there is a rather severe problem with autofocus here – the left side of the LensAlign tool is out of focus and by looking at the right side, you can tell that my setup is backfocusing quite a bit. Instead of showing 0 in focus, it is far off somewhere at 12 in the middle section of the ruler.

- Next, you have to turn AF Fine Tune / Microadjustment on and set a value to compensate for the focus problem. Since it is a backfocus situation in this example, I know that I have to compensate by dialing a negative number. I always start off with an extreme number at -20 or +20, to see how much I need to come down. So in this case, I set it to -20, which turned out to be too much and my focus moved to the front (front focus). Generally, I decrease the number in increments of 5 first, then do additional fine tuning if necessary. For this lens to land perfectly in focus, I had to dial -12.

- The painful part of this process is that there is a lot of going back and forth, since you have to rack the focus ring 3 or more times each time you change the AF adjustment value. The reason why you want to do this, is because Phase Detection Autofocus is often not consistently accurate if you just rely on one exposure.

- Once you get consistently good results using a particular AF adjustment setting, take your camera for a real test. Take some pictures outdoors at different distances and see if things look good. If they don’t, then go back and try the same test at a different distance and see what you get. If you find that you have to dial vastly different numbers at different distances and focal lengths, then you might be better off by turning AF Fine Tune off completely. See some of the additional notes on calibration below.

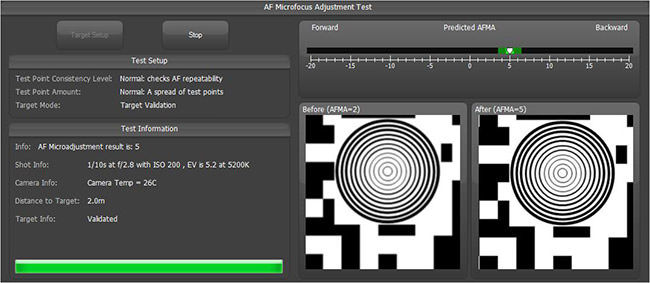

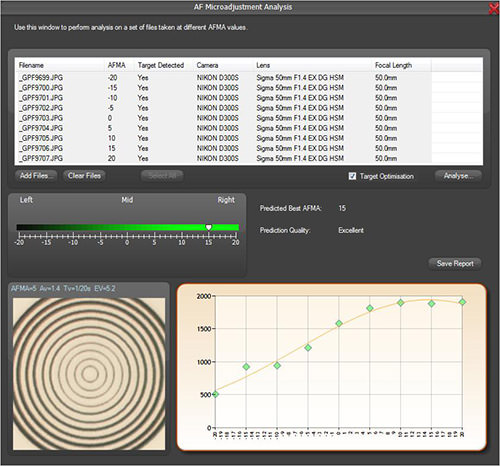

8.3) FoCal: Automated Calibration

The process with automated lens calibration is a little different. Currently, Reikan FoCal seems to be the leader in automated calibration software, which not only performs automated/semi-automated calibration (depending on what camera is used/supported), but also comes with pretty advanced reporting capabilities and testing of each individual focus point.

Here is the process of calibration using FoCal Pro (the software package we recommend):

- You will need a PC or a laptop (preferably, due to potential proximity issues). Connect your camera to your computer using the supplied USB cable, power it on and install camera drivers first (if necessary). Once drivers are installed and configured, install the FoCal software. Once everything is tested, turn the camera off and disconnect the cable (for now, until the setup is complete).

- Make sure that the camera is recognized by the software. Test and make sure that everything is operational.

- Again, you should be in an environment where there is a lot of ambient light, for autofocus to work properly. If that’s not an option, you will have to setup powerful lights to properly expose the focus chart, since a single light bulb in your room will not be sufficient for accurate focus.

- Print out the PDF test chart that comes with FoCal software. You can print it on a regular letter-size paper. A high-quality inkjet printer is recommended.

- Mount the test chart on a flat surface. A straight indoor wall will do.

- Mount your camera on a tripod and place it at a certain distance right across from the chart, depending on the focal length of the lens. The developer recommends to aim for between about 25x – 50x the focal length of the lens in millimeters, so if you are calibrating a 50mm lens, you should test at around 1.25m to 2.5m. Make sure that the chart is parallel to your camera and that nothing is titled. The software will automatically guide you on how to properly align/rotate the setup.

- Connect the USB cable to the camera and your PC/laptop. Start up live view and let the software guide you on how to move/align the test target.

- Once the software shows you a green checkmark, start the automated test process (Canon DSLRs only). It will take a while for the camera to take pictures and adjust the focus. Here is how the process looks like:

If you have a Nikon DSLR, you will have to use the Manual Setting Change (MSC) mode, where the software will tell you what to change on the camera and you will have to dial the values manually (until Nikon DSLR support becomes available in a future release), as shown in the following image:

- The software will analyze each image and tell you which AF adjustment value works best.

- Similar to the LensAlign process highlighted above, I strongly recommend to take your camera for a real test after the calibration process. Test it at different distances and see if you are getting consistently good results or not.

The cool thing about the FoCal Pro edition, is that it allows you to also find out what aperture is the sharpest on your lens and as I have already pointed out above, it can also analyze each focus point of your camera for precision.

9) Calibration Distance

Calibration may vary by distance. I have done a number of tests to show examples of this behavior. What it means, is that if you compensate your camera for a back-focus problem at a certain distance, if the distance between the camera and the subject changes, the focus might be off again.

For example, a 50mm f/1.4 lens at 4 feet might require a -5 adjustment. Moving the lens to 6 feet might require a different adjustment, say -8. And then taking the lens and focusing at infinity might require no adjustment.

This happens due to a number of different factors. First of all, phase detect sensors in DSLRs require a lot of light, which is the reason why all lenses focus wide open, no matter what aperture you set the lens to. So a bunch of variables kick in right away – chosen aperture, focus shift, focus distance, etc. On top of that, fine adjustments at very close distances are much more granular than at longer distances.

Well, the AF fine tuning system is not that smart to be able to cope with all these variables and therefore calibration values might have to be different at various focal lengths, apertures and camera to subject distances.

However, this varies by lenses. On some lenses, the difference is very noticeable, while on other lenses differences are too minor to notice.

10) The Usefulness of Camera Calibration

Another observation that I have after a number of years working with cameras and lenses, is that camera calibration only works reliably well at small adjustments, when it is not extreme. A while ago, one of our readers asked me “how come we only get -20 to +20 for AF Fine Tune, why doesn’t Nikon allow much bigger values like -50 to +50?”.

It was an interesting question that I could not answer at the time, because I did not have a camera and lens combination that required extreme calibration values. While testing various Nikon DSLRs during the last few years, I came across a couple of camera bodies and lenses that had severe back/front focus issues, where something like -20 adjustment had to be dialed during the calibration process.

In cases where a camera body was at fault, the impact of an extreme adjustment did not seem to be so bad (although it was still not very reliable), while when a lens was at fault, dialing above -10 or +10 (especially above ±15) yielded very inconsistent results.

Hence, my conclusion is that if you find that your camera and lens setup requires high adjustment values (negative or positive), you might not want to mess with the whole thing and send your gear to the manufacturer for proper tuning instead. That’s probably why none of the current DSLR manufacturers allow calibration for higher values than 20.

11) Calibration is a Continuous Process

Whether you like it or not, autofocus precision of your cameras and lenses can change overtime. There are many different factors that could influence precision – everything from drastic changes in temperatures, to physical abuse and normal wear and tear.

Some people take it very seriously and perform calibration as often as a few times per month. I personally do it a couple of times before and during the wedding season, to make sure that the gear works as expected.

The goal of my tests is to make sure that the gear I use operates normally. If I see any drastic changes in autofocus behavior and AF adjustment does not work consistently anymore, I contact Nikon and send my gear in for repair. Yes, this process is rather painful and can get costly, but it is worth it, because our clients get the very best quality work from us.

12) Do You Need to Calibrate with a Mirrorless Camera?

Users of mirrorless cameras may be wondering if they need to calibrate their lenses. The short answer is no: mirrorless cameras base their focusing directly on the data coming from the snesor, rather than using a separate autofocus module like DSLRs. Therefore, focus is based on what the final image will look like, and so in almost all cases, it is absolutely not necessary to calibrate a lens on a mirrorless camera.

But if that’s the case, then why do some mirrorless cameras have an AF fine-tuning function? In fact, I just checked my Nikon Z6 and I’ve got an “AF Fine Tune” function that works exactly like my Nikon D500. Why does my Nikon Z6 have this feature?

Well, it’s conceivable that there are rare cases where lenses miss focus for some reason. Perhaps the eye AF feature consistently locks on eyelashes and you’re shooting portraits all day, or perhaps the lens you are using has some sort of communication problem because it’s a third-party lens.

However, such cases are extremely rare. I’ve used several different mirrorless cameras from Canon, Nikon, Olympus, and Panasonic and I’ve not encountered any focus problems with any lenses. Moreover, many mirrorless cameras do not even have a calibration function so if you’re shooting a mirrorless camera, I suggest you not worry at all about focus calibration!

13) Summary

As you can see from this article, calibration is not that hard. Unfortunately, a number of photographers and online resources blindly recommend taking different approaches to lens calibration without fully understanding how autofocus system works, which leads to more frustration and unhappiness from end users.

In my opinion, it is important to know and understand all the details of the process, including possible outcomes before deciding to touch this feature. Despite all challenges, I still highly recommend to play with the AF adjustment feature on your camera and learn how to properly calibrate your camera gear. At the end of the day, you want to get the best out of your equipment.

Is the LensAlign system useful only for auto focusing on digital cameras? I have Leica and Leica-copy film cameras with some lenses whose accuracy of focusing I’m suspicious of. Can I use it for those, and what changes do I have to make to the procedure for them?

Unfortunately Michael Tapes has shut down his entire operation and removed his website tools and downloads. The distance tool was very useful.

Thanyou

Thank you for this and other linked articles. This is wonderful. I’m looking forward to getting the tool and getting stated. Iv read about the focus cal features but nothing this clear. Iv had enough frustration focus issues and will enjoy learning and mastering this.

Thank you sincerely!

No Fujifilm listed, lame…

I’m setting up the AF for a D7000 I converted to 850nm infrared with an internal filter. I use a homemade set up like the Lens Align that I made from wood that has a 1/4 x 20 threaded insert in the bottom so it mounts on a tripod head . I find the Dot Tune method the fastest most accurate way to check where my AF fine tune setting should be . Dot Tune is free and on YouTube .

Great article. I read through the comments and I noted that most are dated 2012 – 2014. In the ensuing 5 years, there have been some developments such as “Dot-Tune” and the Sigma and Tamron docking stations. I have the Tamron Tap-In Console which allows for focus tuning at 5 different focal lengths on my 150-600mm G2 Tamron lens..

Have youThanks considered revising the article to reflect the effects of these new focus tuning devices?

Thank you so much for the insight into lens calibration. While I was weighing the merits of the various methods of performing calibration — I have a 50mm 1.4D Nikkor that appeared to be less sharp than any of my other lenses, I just applied a bit of common sense to achieve a no cost solution.

I printed your test chart, hung it as described, and bracketed corrections as follows: -10, -5, 0, +5, +10. I placed all the images side by side and the -10 was dramatically sharper than the other brackets. I ran some practical tests afterward and I now have ALL my lenses performing at peak performance.

About an hour of my time and zero dollars spent.

Great article. I bought the FoCal Pro software and it seemed to do a good job. I’m not sure what to do though now that I ran the “aperture sharpness profile” test and got what seems like really poor results for my most expensive lens — the Canon EF 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L IS II USM. It showed good sharpness at between 5.6 – 7.1 and just average at 8 and 9, dropping precipitously into the “below average” category at 10 and smaller. The lens is nearly 2-years old (so out of warranty). Are there alternatives to sending it to Canon for adjustment?

Really helpful article .

Great technic for the Prime lenses only But not workout with the zoom lenses .

I had focus problem on my D600 .

When calibrate with the 24 to 70mm f/2.8 it difficult .