After having some experience with seabirds in Scotland, Norway, Canada and Alaska we wanted to watch and photograph penguins in Antarctica and the sub Antarctic islands: But how to get there? There is no possibility of individual travel in and around this huge continent. So after some research we decided to use a cruise ship as a base for our travel plans. Fortunately in 1993 we were asked to share a book project on Antarctica by a German (Munich based) publisher. They had already sent a photographer to Antarctica and needed text material on nature, ecology and species accounts. Both of our studies we cramped with scientific stuff on exactly these topics. So we did half of the books text. The other half – a text essay – was done by a well known travel author. This book appeared during spring 1994 sold very well. So we used it to appeal for jobs as bilingual biology and geography lecturers on the German- an US-managed ship “World Discoverer.” We were invited to come to the agency in Hamburg and… we got our favorite trips!

This very first travel to Antarctica was starting in December 1995 and finished end of January 1996. We were very lucky to get two trips each from Ushuaia, crossing the Drake Passages screaming 50 ties and going strait to South Shetland and the western Antarctic Peninsula. The second trip was even better. Its first part was similar, but then we also went to the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula into the Weddell Sea with lots of huge icebergs and then to South Orkney, further on to South Georgia and even to the Falkland Islands. These two trips covered 90% of all possible Penguin sites between South America and Antarctica!

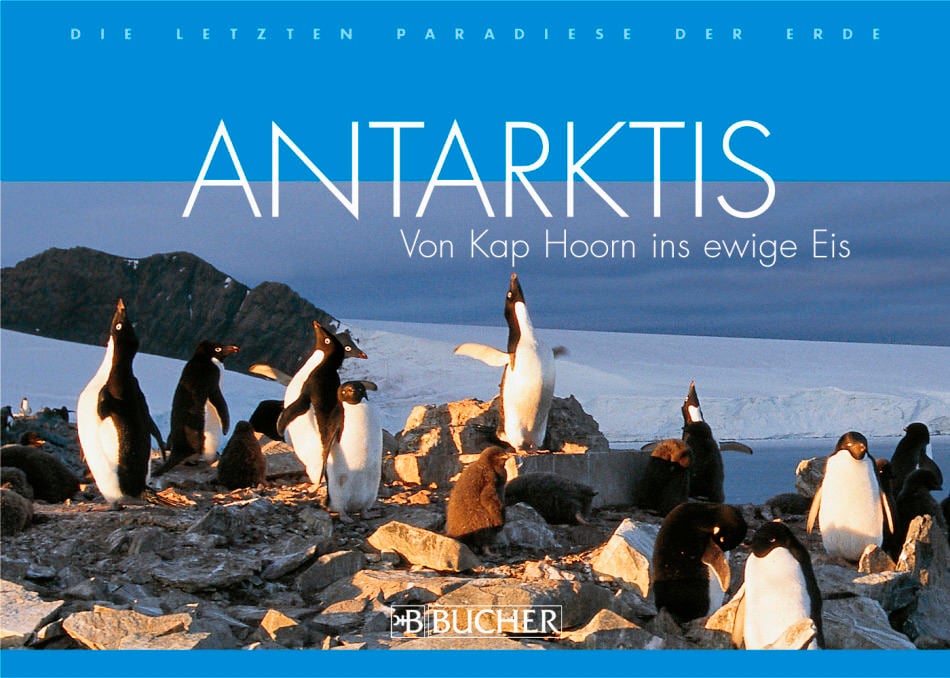

Mamiya 645super, Sekor 2,8/55mm, Velvia 50 © Achim Kostrzewa

For us, it was like heaven. So I packed really a load (about 50 kilograms) of camera gear: one Mamiya and four Nikon bodies, about 14 lenses to cover every possible opportunity. It sums up to about 60 kilograms of carry on luggage, including 300 rolls of Velvia 50 and Sensia 100 film and an additional bag with 10 kilos of slides (haha, in 1995 there were no laptops with powerpoint available, we used Kodak Carrousel projectors) and books for the lectures. Two tripods, my big Linhof studio and a smaller Manfrotto 055B each with ballhead, were put into the big bags. We flew from Frankfurt to Santiago de Chile, stayed overnight in a nice hotel and in the next morning on a charter flight we went strait to Ushuaia (Tierra del Fuego) where we got on our ship. Excluding the night at the hotel, it took us 42 hours from our home near Cologne to get there. Group travel was a real new experience for us, we were accompanied by about a hundred Antarctic crazy people from all over Europe. Acting as staff, not crew, we got a nice cabin with bull eye window, two comfortable beds, a private bath, but only very little space to put our things. Much less than we were used to have in our motor home.

Nikon F4s, AF 2,8/80-200, Velvia 50, tripod © Achim Kostrzewa

For the next two days our duty was to give an overview on the biology and ecology of penguins, other seabirds, whales and seals. And a bit of the geographical aspects of western Antarctica, while crossing the Drake Passage. With no problems of seasickness on my side the rest of the time I was out on the different decks to check for photo opportunities, viewing angles and the best sites to capture whales and seabirds. Every time out on the decks I carried my F4s with an AF 4/300 tele-lens and a mid-range zoom on my manual FM2 with me. Coming closer to the icy continent the photo opportunities got better. I was able to capture some lonely Wandering Albatrosses, Humpback Whales and we were accompanied by hundreds of Cape Petrels.

Nikon D300, ISO 400, 420mm (=630mm equiv.), f/5,6, 1/2000sec. © Achim Kostrzewa

Table of Contents

What Kind of Equipment to Bring

So what you really need is one APS-C camera with a 18-300 mm to cover everything. This set up would be also good enough to publish in (your local) newspapers, the internet or giving Powerpoint slide talks. You could also use a set of 18-55mm and a 55-200 lenses with a second body as back up. Micro Four Third cameras would be fine, too.

Please note: Back ups are important on such a trip. If you loose your one and only camera due to saltwater spray or even rain and snow, you might be finished with your photography. We have now more and more weather “sealed” or resistant cameras, but you have to clean them as well after every contact with salt water spray…

So called “Full Frame” (24 x 36 mm) sensors would be nice to have. Here a 28-300mm would do. I, myself use both sensor sizes with my D300 and D700 Nikons. And, by the way, I am not very fond of these can-do-everything-zooms. Since many years I am used to a variety of different Nikon lenses. The D300 with AF-S 4/300 for the longer reach and the D700 with some wide angle primes for the quality (occasionally the AF-D 2,8/14mm and always the manual AIS 2,8/24, AI 2/35 and AIS 2,8/55 micro because of there built and optical quality). My mid-range zoom is an old AF 3,5-4,5/28-85 N, which is optically really superb. And on the long end I switched from the heavy AF 2,8/80-200 to the more light weight AF-S 4/70-200 VR. But using the old one as a back-up zoom. Both AF-S lenses can be combined with the 1,4x Nikon extender TC 14eII. Both bodies can be combined with the MB-D 10 Speed Kit. This gives 8 frames per second on the D700 and can also to be used with AA sized batteries. Both cameras also share the same chargers and EL-3e batteries. Bring also at least three batteries for your camera: one in the cam, one spare always in the pocket of your trousers to keep it warm and one in the cabin loading. Keep in mind that mirrorless bodies have a higher power consumption and small batteries, so bring 5 batteries minimum.

As long as the weather is quite dry and the light is good, I still use my film Mamiya with waist-level finder, Gossen Variosix Spotmeter and three lenses: 55, 80 and 150mm. On the moving ship never use a tripod due to the vibration of the engines. Everything has to be done handheld. The formula for sharp pictures on land is: 1/focal length x 2. That would be at 50mm 1/100 sec. On the ship please double this value to 1/focal length x 4 = 1/200 sec. On a zodiac double again – never go below 1/500 sec. with your mid-range zoom. That’s why high ISO is often more important than high resolution.

- For landscapes from the deck of the ship my preferred camera settings are fully manual or aperture priority to control the depth of field, “low” ISO and always checking for enough speed. The AF setting is always “single-shot” and choosing the AF point manual, because otherwise you might fail.

- On the zodiac photography is much more documentary and photojournalism. You have to be quick with your camera. So use shutter priority with 1/1000 sec. minimum depending on the speed of the Zodiac and apply ISO automatic.

- For flying birds and the occasional whale my 300 prime is always wide open, on aperture priority, and the ISO setting in manual mode according to gain enough speed. But you could also use ISO automatic (ISO 400-3200) as well. If you like to capture smaller birds like petrels the 1.4x extender might be a good idea.

Nikon D700, AF 2,8/80-200@140mm, ISO 400, f/5,6, 1/2000sec. © Achim Kostrzewa

I also shot many landscapes with the 300mm on my D700. Another possibility to capture nice frames is to bring the ship itself and its people into the picture, either to frame a landscape, or to show the magnitude of an iceberg. Then the mid-range zoom is the one. If you take a strong wide-angle instead, you get a big foreground (ship and/or people) but the landscape will be too small for my taste. So the 35mm on my D700 and the 55mm in case of medium film format are my preferred focal length for that kind of work. To capture people and photo situations on the zodiac some times a wide-angle zoom like a 18-35 helps but normally my 28-85 works well enough.

Sony R-1, 30mm (equiv.), ISO 160, f/9, 1/250sec. © Achim Kostrzewa

What is Really Important?

- Fast AF even in dim light

- High ISO capability, esp. during worse weather conditions

- Rain gear for your camera(s), always apply the hood on every lens, it helps much

- Always have a spare for everything you really need

- A so called “dry bag” to put your camera back pack in during zodiac tours and “wet landings” (see part two)

- Bring your manuals with you but leave them in the cabin

- And: RTFM

- Last but not least it is most important that you are very accustomed to your camera gear, train your preferred settings at home while on excursions during bad weather, rain and storm you will have no time to do so…

- So after all the camera does not matter very much if it gives a certain level of quality

- What really matters is weather and luck

Zodiac Landings and Photography

Nikon D300, AI 2,8/28mm, ISO 200, f/16, 1/50 sec., tripod © Achim Kostrzewa

Most of our landing experience (now several hundred wet Zodiac landings) comes from the western Antarctic Peninsula and the Islands of South Shetland, South Georgia and Falkland. But we did trips to the islands off New Zealand and Australia (esp. Macquarie Is.) as well. 99% of all landings in Antarctica are “wet” mostly done by Zodiac or similar inflatable boats. Your need knee-high Wellingtons to wade the last meters onto the beach. My cameras always survived well stowed away in a Lowepro Phototrekker and a big waterproof plastic bag. Nowadays, we have these wonderful dry bags… One camera with a 35mm prime or a mid range zoom you can strap around your neck to get some shots from the boat ride and the landing, if conditions permit. If it’s raining, I use a big zip lock bag for this.

Nikon FM2, 2,8/28mm, Fuji Sensia 100 © Achim Kostrzewa

Nikon F2A, AIS 2,8/24mm, Sensia 100, handhold, sitting on the beach © Achim Kostrzewa

The landfall is always the day’s highlight: the excursions to seal and or penguin colonies. Sometimes twice or three times a day, if weather permits, it is simply gorgeous. The experience to sit on the edge of a colony of thousands of pairs of penguins is stunning in every aspect: the smell during warmer days, the noise, the activity and of course the curiosity these birds have towards their visitors. The best opportunity to study courtship, mating and nesting of different penguin species is during December and January. For landscapes,early spring and during late October/ November and fall in March might be also an option. Fledging of penguins is during February until March. Renate has more experience with these times of the year. But the weather is often less favorable (see photos of part one) and the penguin colonies got more and more empty, that’s why this is not my favorite time to go.

After being the first time on the “World Discoverer” as biology and geography lecturers, we were invited every year to accompany different trips, ships and travel agencies. So the seabird colonies of the western Antarctic peninsula became our “winter” home during most “southern summers”.

On the first trip, I took a load (about 50 kilograms) of camera gear with me. We were thinking that this might be the one and only opportunity to take photos in this very special environment…

Later on, when Antarctica became more familiar to us, I always used two Nikon bodies and about seven lenses. During the autofocus film age, it was the F4s and F801s. My beloved FM2 as a back up. We had to get rid of the bulkiest and heavy stuff, the wonderful Nikkor AIS 3,5/400 IF-ED (3 kg) and its smaller companion the AF 4/300 IF-ED (nearly 1,5 kg). In 2001, they were replaced by the new AF-S 4/300 (1,4kg) with the new Extender TC14E-II which became my favorite combo. In 2007 I went partly digital with a Nikon D300. In 2010 a D700 made me to a mostly “digital” photographer, but still using my film Mamiya 645 super during good weather conditions. The combination which gave the most keepers over the years have been my F4s with the AF 2,8/80-200 ED pro zoom. Now the D700 with 70-200 is the one. For animal photos my sharp and lightweight AF-S 4/300 is very useful.

Our next trip will be starting at the end of December 2015, going exclusively to the Falkland Islands for three weeks. You are allowed to bring 20 kg in total on the small planes for the inter-island flights. So I have to downsize again. My gear will be two Nikon bodies, AF-S 4/300 and 4/70-200VR, TC 14, AF 28-85N, AF 18-35. My new Novoflex TrioPod with its two Leki walking poles and one monopod making a good lightweight tripod for this excursion. Together with batteries, charger, storage cards and some filters it sums up to 10kg. Two small AIS lenses (2,8/24 and 2,8/55 micro) in my parka pockets will give some back up. I have successfully tested this set on a trip to Alaska and B.C. in August last year.

For the Falklands, 10 more kilograms of rain gear and warm clothing in a dry bag will do. My boots I will have to carry during the whole flight from Stanley to the different islands. And the laptop will be left at home, but I will bring a card reader and a small hard disk drive with me. Hopefully, some of the places might have an accessible computer.

When you have arrived on the beach safely guided by your zodiac driver and some helpful hands ashore, put your cameras out of the backpack and follow your nature guide. Due to the Antarctic Treaty, we are not allowed to land parties exceeding 100 people. For every group of twenty, we have an extra guide. On one of the smaller cruise ships with 100-125 passengers, you have more time ashore and often more excursions per day. 100 people ashore, 25 in the Zodiacs taxiing, photo time could easily be two hours or more per landing. If you go by a bigger vessel with about 200 or even more passengers, two groups (A and B) are formed. Changing normally with each landing. But when we have to call the first group in because of deteriorating weather conditions, there will be no landing opportunity for the second one. Some islands which are critical due to species like Wandering Albatross nesting, allow only 50 people. So if you are on a big ship, there is no chance to go. You have to use one of those Russian ice breakers with 50 persons only. There are some sites in New Zealand’s part of Antarctica, you can go by Zodiac only close to the beach but nobody is allowed to land for the safety of some really endangered species like Snares or Erected-crested Penguins. If you want to see those, very rare species you have to stay in the Zodiac and photograph from this not very stable platform.

Nikon D300, AF-S 4/300, ISO 640, f/5, 1/2500 sec., handheld; my second camera around my neck was the D700 with 80-200 zoom © Achim Kostrzewa

Due to the erratic movement of the boat and the birds, image stabilization does not help very much. Use 1/1000 sec. or faster shutter speeds instead. Image stabilization works best, if you are on dry land and need to stabilize your setup while shutter speed is below 1/500. So I would not recommend buying an extra stabilized body or lens and otherwise switch off your VR, IS, IBIS or whatever it may be called. There are some interesting posts on how and when to use image stabilization on the Internet, so you can read those to understand how stabilization works in detail and when it should or should not be used.

Nikon D300, 200mm, f/8, 1/1000 sec. handheld © Achim Kostrzewa

How to photograph from a Zodiac Boat

- Always remain seated until the boat stops and the driver tells you to get up if you want

- Always move slowly and watch your companions

- Always stay on your side of the boat

- It is not a good idea to change lenses, therefore I use two bodies with different lenses

- If you really have to change lenses be careful especially with digital equipment. Use a plastic bag. I am able to change lenses between two bodies within seconds, but I am used to stay on a moving boat

- Don’t bang your tele lens into your neighbors head :)

- Don’t carry your backpack around your neck, if you fall into the water it might block your life vest to inflate

- Always carry some dry tissue towels in your parka to clean up spectacles or front lenses

- Secure your sunglasses by a sports strap

- Don’t worry, from my experience the chances of staying safely in the boat are quite good: there is one guest per one hundred rides falling into the water, mostly amateur photographers fighting with their cameras

- More people came into contact with salt-water during wading ashore: overwhelmed by the sheer scenery they stopped wading and got caught by the next wave…

- On the zodiac, photography is much more documentary and photo-journalistic. You have to be quick with your camera. So use shutter priority with 1/1000 sec. minimum depending on the speed of the Zodiac and apply Auto ISO.

Nikon D700 with my mid range 28-85 zoom © Achim Kostrzewa

Ashore

Land excursions might be difficult. Anyway, they are a long-lasting experience. But be well prepared: don’t drink too much coffee or tea. If you have to wash your hands you have to go back to the ship! Bring enough spare batteries and cards. Some people take a thousand pictures on one excursion but miss the “decisive moment”. From my point of view, it is best to sit down and have some nests in close observation, build your tripod and just watch and wait for some action. Better if you prepare “the journey of your life” by studying bird books at home and follow the lectures on board. I am used to having a small old-style notebook (made from paper) and a pencil with me to put down date, time, weather and other useful information. At home these notebooks fill a whole shelf now, but were a trustful source of information when writing articles.

What to bring ashore

- Warm waterproof clothing, silk underwear, fleece trousers and jacket, two pairs of gloves (one water resistant for the zodiac, one pair of thin leather gloves for photography and if its really cold and windy a second pair to pull over)

- A piece of isofoam to sit upon, please strap it to the parka or backpack, because they tend to fly right into a colony…

- Sun glasses, hat

- Photo gear with spare batteries

- Binoculars for birders only

- And please, obey all the rules of nature conservation according to your briefing on the ship

- No food or smoke

- Don’t leave any trash. During the old film days, we always found empty containers

Because you will not have too much time for photography, it is better to concentrate on some nests, for instance, interactions between birds on the shore or birds with the landscape, landscape with typical birds, your fellow travelers interacting with penguins, etc. Well-informed staff will know what is to see in which places, because the are “best sites” for every species on which you should concentrate. The best advice is to start with your research (please not only on the Internet. Also consult old-style books, as they often contain much better information) at home after getting the travel schedule with time and places to go. But often, there are changes due to weather or adverse wind conditions. Once we had a well=known German nature photographer aboard. He insists to go to “Salisbury Plains” as it was printed in the travel announcement. We sailed along the coast but due to wind, swell and surf, we were absolutely unable to land there. So we had to choose “St. Andrews Bay” instead. This was the best place I have ever seen for King Penguins, much better than Salisbury, which is fine, but he was still muttering, because he wanted to shoot what dozens of other professionals had done before…

Nikon D300, AF-S 4/300, ISO 200, f/20, 1/60 sec © Achim Kostrzewa

Nikon D300, AF-S 4/300, ISO 200, f/6,3, 1/640 sec. tripod © Achim Kostrzewa

It might also a good idea not only to copy photos and scenery that others have published before, but to go out there and find new views and visions of other birds than just penguins. Try action, portraits, close-ups with your strongest tele lens, change DOF from super wide and deep to wide open aperture with blurred background and a smooth bokeh. During “bad” weather shoot portraits and close-ups. When it shines, do more landscapes. There is so much to see!

Nikon D700, AF-S 4/300 + TC 14E-II, ISO 200, f/10, 1/500 sec., tripod flat on the beach © Achim Kostrzewa

Nikon D700, AF-S 4/300, ISO 200, f/8, 1/250 sec., camera placed on the backpack, flat on the ground © Achim Kostrzewa

My camera settings

I use two type of settings:

- Fully manual for landscapes

- Sometimes (when there is some time pressure) also aperture priority to have control over the depth of field and let the camera control the shutter speed

- Action setting for animals:

- Shutter priority

- My 300mm prime is always wide open, also with extender

- Dynamic AF (21 AF points)

- One single AF point which I choose manually via my thumb

- Note: It is strictly prohibited to use flash

Back on the Ship

On a cruise ship, life is much more comfortable! Even if you get really wet on a landing trip you can easily dry up everything in your cabin. Be careful with your camera stuff: don’t bring the ice-cold cameras into your warm and moist-filled cabin to dry them out. Best idea is not to overheat your cabin. Clean your stuff first from the outside with a canvas handkerchief and then put each into a dry zip lock bag, press the air out and then go to your cabin. So you keep the moisture out. After having warmed up for an hour or two (the gear not you) you can unwrap it and clean your front lenses, filters and camera bodies, finders, everything that might got some saltwater spray. I use 70% medical alcohol (diluted with aqua bi-dest) for this. Also dry out your backpack and dry bag after every a Zodiac ride…

Some Final Notes

Even during summer in Antarctica, you can have extreme weather, so be prepared for nausea from seasickness, getting wet from spray during zodiac rides, losing parts of your equipment due to saltwater spray or rain, if you don’t keep them dry.

Be always careful with your travel companions, your own safety and of course the safety of the animals around you. All rules on safety and nature conservation make a lot of sense, so please strictly obey them, even if you lose a shot or two. If you don’t, I would warn you once, the second time I would send you back to the ship immediately to see the captain. And I am sure that other nature guides/biologists will do so as well, because the license of the ship to land people depends on that.

Antarctica is a wonderful place to go – for me the best place on earth – so we have to enforce nature conservation for future generations. And keeping a distance of 5 meters to penguin nests, 15 to albatrosses and 50 to giant petrels nests should be really no problem… Especially Fur Seals or Sea Elephants will go for you, if you come to close. Move always slowly, don’t run or shout. Just watch your surroundings carefully, with great respect and have fun, and the best photo opportunities will come.

Nikon D700, AF-S 4/300, ISO 200, f/8, 1/250sec. tripod rather flat on the ground © Achim Kostrzewa

Article and all images are copyright of Achim Kostrzewa. All rights reserved, no use, reproduction or duplication is allowed without written permission.

Since December of 1995 we have 27 complete journeys to Antarctica under our belt. That is Renate, an animal ecologist, geographer and writer and me, Achim Kostrzewa, animal ecologist, geologist and dedicated nature photographer ever since. During summer time we have done quite the same amount of trips to the Arctic like Greenland, Svalbard or Frans-Joseph-Land.

We run our own home page for more than 10 years now (all in German: www.antarktis-arktis.de) and have published 20 books with German publishers and numerous articles. Achim has his own photo blog started in 2012.

Thank you very much for your very nice article and photos.

Achim, thanks for sharing your journey with your amazing journeys to this mystical place. I appreciate your detail and photos very much.

Thank you, “Diva”, the second part is on its way…

This was awesome. Thanks for sharing both the information and the great images.

Mr. Kostrzewa,

Thank you for sharing your photo essay. Your story and photographs are captivating, moving, and brilliant. One of the best I have read here or elsewhere. I congratulate you and your colleagues for possessing the sense and spirit of adventure to embark on an exciting journey to the far reaches of the Earth to explore, marvel, and document the harsh, yet pristine and beautiful, sights and sounds of the Antarctic.

What you have shared with us is every nature and adventure photographer’s dream. In some of your photographs, I can feel the raw emotion, the flowing adrenaline, feel the cold air, and hear the crashing sea as you saw it and felt it behind the lens. Really awesome!

I applaud your planning and skill to seek out the photo opportunities that you envisioned and for faithfully recording those photographs under physical and psychological conditions that would strain the patience and fortitude of even the most experienced and talented photographers. Bravo!

As part of your strategic planning for your exploration, I wholeheartedly agree with your approach to mapping out, so to speak, and choosing the tools that you deemed instrumental to take command and control of the prevailing conditions, in terms of the light, the scenes, the action, and the many pitfalls along the way. Indeed, employing a broad array of formats and lenses and alternating your methods, technique, and approach as the conditions dictate to stay on top of the situation are sage advice for the nature photographer.

Further, the “dry bag” that you mention for your pack and gear under these inclement conditions is superb advice. I look forward to reading Part II of your essay to compare notes. In my two excursions in 2013 to explore the rugged wonders of Iceland (a two week tour/workshop with other photographers and a subsequent 1 week solo hike through the Highlands), for example, I found the dry bag to be a necessity, as the weather often changed from dry and windy to wet sleet and snow within minutes to hours. Bringing an ample supply of desiccant packets to keep in smaller individual dry and air tight bags were also instrumental to minimize moisture exposure under shelter and during the various transits.

Mr. Kostrzewa, I just viewed your photo blog that you kindly shared with us via your link. I immensely enjoy your photographs of the colorful and volcanic landscape in Timanfaya National Park (I had never heard of that park – what a find!), wildlife (in particular, the vulture, puffins, and grey whale), as well as the moody seascapes in the fjords of Alaska and Norway. Ahh, I am now going to have to place the Canary Islands on my ever growing wish list of places to hike, explore, and photograph.

Thank you again! I look forward to your second installment on PL.

Cheers!

– Rick

Thank you all for your interest. I am working now on the second part…

Achim

Thank you for sharing here on PL. Wonderful advice from an experienced photographer for us all. However, it looks cold and I’m not going. LOL

Hi Mike,

No, Not too cold….

WE have somewhat between 0 and +5 centigrades Celsius during december and january. It depends on the wind Speed and Sunshine of course ;-)

So it. can Feelings Quitte warm compared to Yellowstone during winter.

Achim, I lived in South Florida for about 24 years. When it got to 21 degrees C I was in long johns. LOL

Oh gosh, my iPad thesaurus changed some words into Germish…

Love it! I was taken on a journey by your words and images. One of the memorable posts on this site. Thank you!

These trips must have been exciting. Your stories raise humbleness in me, thank you for sharing.

Achim, thank you very much for that glimpse into real-life photography, where the main concern is to get the shot, hence weight and portability. I really appreciate this series of posts about photography in the field in Nasim’s website.

When you advise mirrorless and APS-C cameras, I suppose it is to get long reach without too much weight, or are there other reasons?

JD

Hi Jean,

during the last year I was thinking about buying a smaller camera model like an Olympus m3/4 or Fuji XT1. But after checking lenses and available accessories I decided not to change from my Nikon stuff. The Oly has only a quarter of the size of a full frame sensor, but is not much smaller than the Fuji with its APS-C Sensor with an sensor area doubling the Olympus. So I would recommend the two formats I use: APS-C and FF.

This is because I have a lot of compatible stuff to use. And the picture quality for my kind of use

(book publishing) is fine. Of course in DX or APS-C the reach of my small travel 300 prime is better in the smaller sensor, the D300(s) is fairly lightweight, like the D700 if you don’t apply an extra battery holder to it. For battery power you don’t need to do so, because one battery gives 1000+ photos.

Coming back to mirrorless, the camera bodies themselves were more lightweight, yes, but this is not true for pro lenses, an 2,8/40-150 is around one kilogramm, like my 4/70-200 Nikkor.

And by the way, I do not like these flickering electronic finders…

Anyway, an Oly or Fuji with two of the pro lenses and a 1,4 extender might be fine, if the auto focus is okay. In the case of the Fuji you could probably use something like the XE2 as a back up.

After all, the camera does not matter too much, if it is sturdy enough to survive this environment .-)

Best wishes

Achim

Vielen Dank, Achim, for your detailed reply. Looking forward to your next paper.