Have you ever wondered why you are instantly drawn to some photographs, but not to others? Or why some of your images lack that wow factor that you see in other’s. It may be related to how you compose your pictures. How a photograph is composed has a huge impact on how long we look at it. The longer our brain is allowed to wander through an image, the more likely we are to like it. Photographs that are not composed well do not have staying power, and are quickly discarded by our brain. In this article I want to discuss four very basic compositional tips. I won’t be talking about the “rule of thirds” or “leading lines”, but rather four pointers you should consider before you take a picture. These tips will save you a lot of post processing time, and will allow you to create much stronger images.

Table of Contents

1) Horizontals and Verticals

When our brain sees something that it knows should be horizontal, like a distant horizon, but it isn’t, warning bells go off. Instinct tells us that there is something wrong. This usually translates into “I don’t like this photo very much”. The same thing happens when objects that should be vertical, like a building, are not.

Horizontals are a relatively simple thing to fix. It just takes practice and being aware of the horizon before you click your shutter. In most cameras you can turn on a grid display in the viewfinder. Try to make a conscious effort to level the horizon so that it is parallel with one of the gridlines. I have a tendency to drop my left elbow when I am holding my camera. I have to work hard to remember to lift it up so the Gulf of Mexico doesn’t drain off to the east!

This first shot of a windsurfer doesn’t look right because the horizon is tilted.

Being more aware of the horizon led to a much better image here.

Verticals can be a bit more challenging to keep upright in the viewfinder. There are two different issues that can happen to vertical lines. The first issue is similar to a slanted horizon above. It happens when the camera is rotated, as is illustrated in this next photo. Notice how the power poles are not standing upright.

In this situation, you need to turn your camera so that the poles are vertical. Use the layout grid in the viewfinder to help you do this, just like you did to level your horizon. For this shot, I was riding in a boat, so keeping my horizon level and verticals truly vertical took a bit more care. Here is a second image shot just a few seconds before this last one, and converted to black and white.

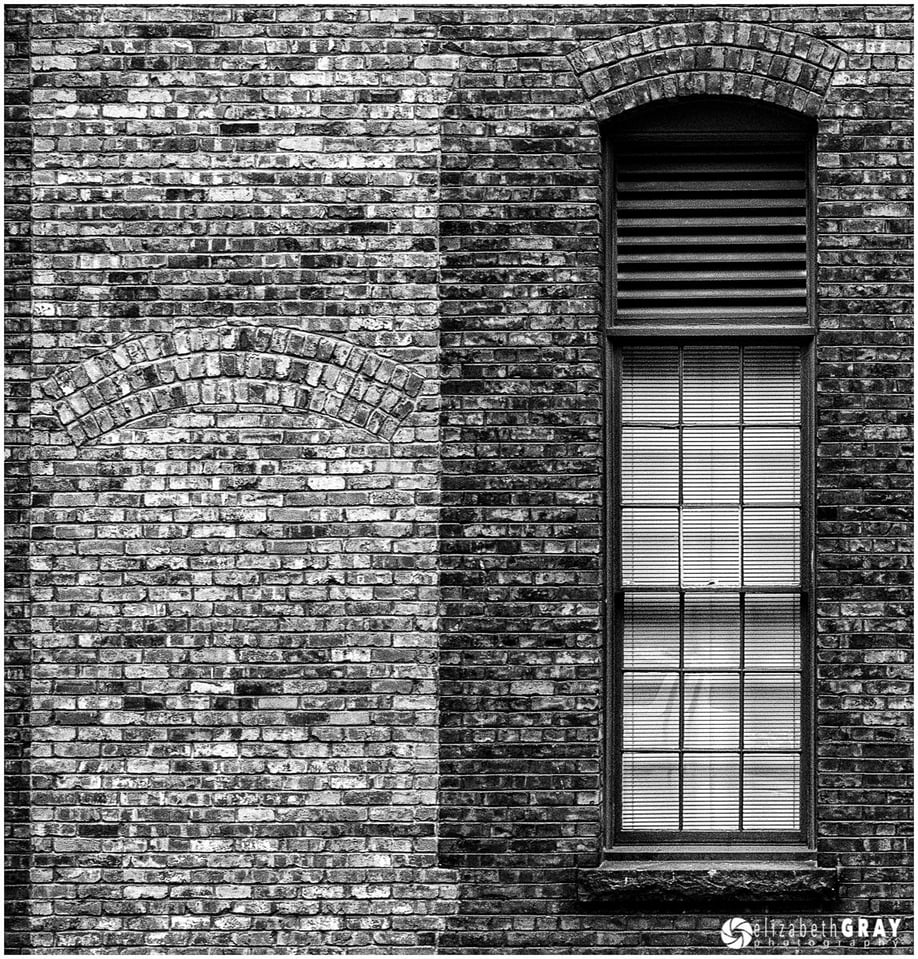

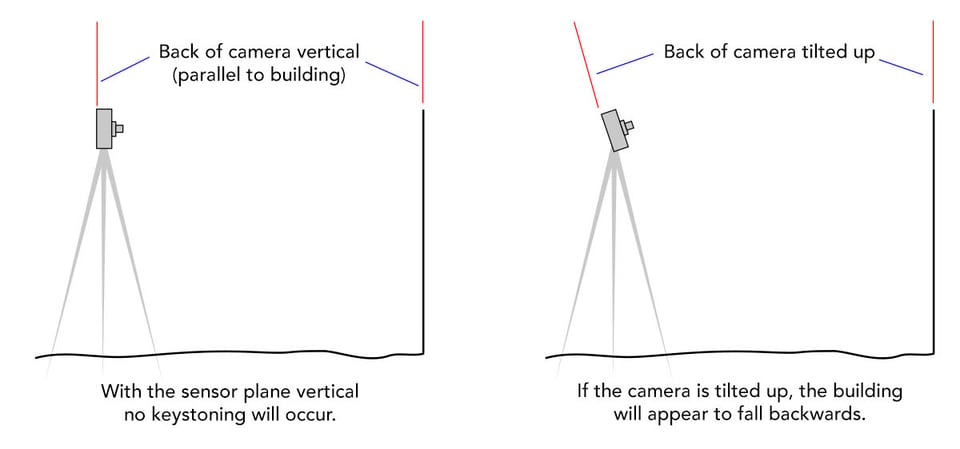

The second situation that can occur with vertical lines can be a bit more difficult to correct in-camera. I mention it in this article so you can be aware of it and correct it if possible. However, sometimes a cure can only be found using post-processing software or an expensive tilt-shift lens. In this photo, notice how the vertical building appears to be falling backwards. This is an effect called keystoning. Keystoning is defined as the converging of lines that are supposed to be parallel. It occurs when the sensor plane (aka the back of the camera) is not vertical.

If at all possible, try to keep the back of the camera parallel to the face of the building so that the sensor plane remains vertical. In this sketch, the camera on the left will not cause any keystoning while the camera on the right will.

For this photo of an old window and brick wall, I had to stand across the street on a set of stairs so that I would be up high enough to look straight on at the wall. Had I stood at street level, I would have had to angle my camera upwards. The only way to stop keystoning in the field is to keep the back of the camera vertical.

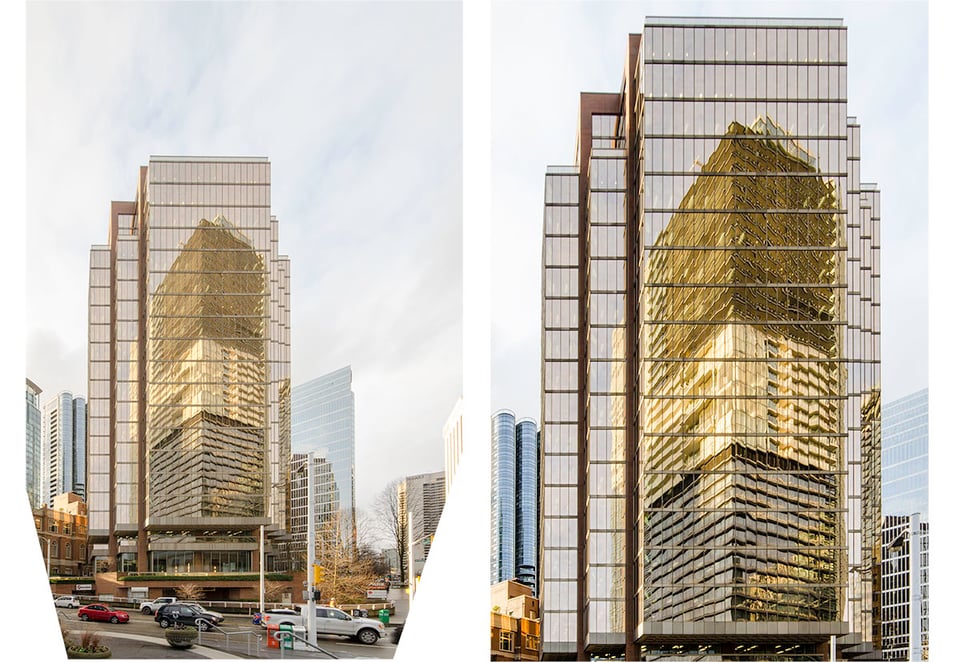

This photograph gives you an idea of where I was standing to keep the wall from tilting back.

Sometimes it is impossible to shoot from a position that keeps the back of the camera vertical. For example, if you want to take a photo of a tall building, even with a very wide-angle lens you will have to angle the camera upwards. This occurred in the photo of the high-rise above. In situations like this you will have to correct the keystoning in post-processing. This is very easy to do in any program that offers perspective corrections, like Lightroom. In a future article I will discuss how to correct perspective in Lightroom. In the mean time however, if you can’t avoid tipping your camera upwards, give your subject lots of room. You will need to do some cropping after you correct the perspective in post. Here is the photo of the high-rise after I did a perspective correction in Lightroom. Notice how the final version had to be cropped quite substantially because I lost the bottom corners of the image when the perspective was corrected.

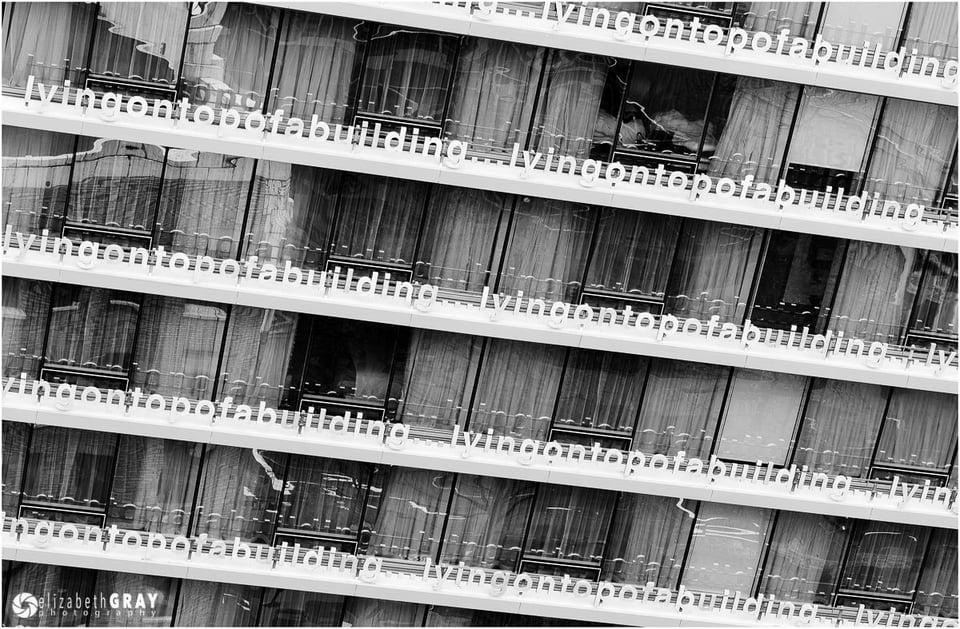

On the flip side, some very interesting photos can be taken by intentionally tilting verticals and horizontals. If you try this, do it with gusto! You want to make sure that the viewer is clear that your composition choice was intentional.

2) Border Patrol

One of the most common distractions I see when critiquing photos are bits and pieces protruding into the edges of the frame. These distractions cause your eye to wander away from the main subject. Yes, you can “fix” them in post-processing by cropping or cloning, but why not deal with them at the source? These edge distractions often take the form of branches, bright spots, or a small bit of something that just clearly doesn’t belong in the photo. When you are framing an image, before you take the shot, look around the borders of your frame. Are there any distracting elements? If there are, adjust your composition just a bit. Usually a simple step to one side, or a slight change in camera angle can fix the problem before it is a problem! When I take a photo, besides checking the histogram for exposure, I quickly glance around the edge of my frame to make sure that I haven’t got any of those nasty little distractions that try to take the spotlight away from my subject.

When I took this image I noticed the distracting branch at the upper right edge. If I tried to crop this in post, I would have lost some of the red tree in the background. By shifting to the left, I was able to remove the distracting branch. As an added bonus, I was now able to get the entire group of red trees in the background.

In these photos below, I tried several different perspectives. There is one annoying branch in the first photo. In the second, I tried unsuccessfully to frame the church using the tree. However, now I had a distracting shadow as well as two intruders along the right edge. The third attempt still had a small border distraction. And yes, I know how to use the clone tool and the spot healing brush in Photoshop! However, if I can get it right in-camera, it will save me a ton of post-processing time. These are all uncropped images.

Here is the final composition. The trees around the edge of the frame are intentional and help to frame the mission. My vantage point also eliminated the shadow on the ground. As a side note, the mission does display some slight keystoning, but this could be corrected in post.

3) Intersecting Objects

When two unrelated visual elements touch or overlap, they often draw unintended attention to their intersection. In this series of photos I was trying to capture a little blue heron on a piling. In the first picture you can see that his head is merging with the dark grasses across the bayou. By taking a few steps to the left and climbing a small incline, I was able to get a much better image.

Here is another frame from the windsurfer series. Here the kite and the horizon brush up against each other. I don’t feel this is as strong an image as the one at the top of this post where the kite cuts the horizon closer to its center. In that image, although two important elements of the frame intersect, they do so in a commanding way, and not half-hardidly.

Sometimes it is not possible to change your vantage point. However, patience often pays off. Notice in this first image of several sandhill cranes in flight, that two of the birds’ wings are overlapping. Waiting just a few seconds, and keeping my fingers crossed, I captured an image where I can clearly see all the birds individually.

4) Simplifying

It is easy to have your subject become lost in a busy or cluttered image. Whenever possible, try composing so nothing competes with the subject. This can be done a couple of ways.

Try shooting the subject from different angles. Sometimes changing your perspective, even slightly can be the difference between a good photo and a great one. Here are two images of the same yellow lotus flower taken a few seconds apart. Although the background is nicely blurred in this shot, it is very busy. There are several highlights at the top right that distract the viewer from the bloom.

For this photo, I positioned myself further to the right of the plant. This put the bloom in front of the water and not as much of the vegetation. The result was an image with all the focus on the flower and none on the background.

Here is another example of how changing perspective can improve a picture. The top left corner of this first shot completely takes away from the branch and its beautiful fall foliage. There is even a telephone pole visible in the background. Near the top right corner is a bright white spot that also detracts from the subject.

Moving to the left, and stepping a bit closer has created a much better image.

Another way to simplify your composition is to clean up the scene before you take the picture. Pick up any litter. If there is a distracting object, temporarily move it! Just make sure that you put back everything before you leave, except the litter! That goes in the trashcan! I have a short length of string in my camera bag and some cloths pegs. I use them to gently pull back branches when I’m taking flower shots and macro images. If I’m in my own garden, I often do some “pruning” if I notice a wayward branch. Don’t try this at a public garden or park though, the string and cloths pegs will work great here.

In this shot, notice the piece of tape in the corner and my shadow. I know I could have fixed both of these using Photoshop. But I can guarantee you that it would take a hundred times longer than it did for me to bend down, pick up the trash, move so that my shadow was not in the frame and take a second image.

Raw Image

This second image is much “cleaner” to look at!

Processed in Lightroom

5) Conclusion

In the digital age of photography the majority of photographers press the shutter release quickly and frequently. After all, a digital image is free (minus the cost of the camera, lens, post processing software … well you know what I mean). However, what most photographers neglect to consider is the cost of their time. Going through hundreds or worse, thousands of images can be very time consuming. You will save yourself countless hours reviewing photos and correcting them in your favourite post-processing program if you slow down and think about your composition first. This doesn’t mean that you have to get it right with the first shot. But review your images after you take them. Ask yourself these questions before moving on to a new subject. Are my horizontals and verticals actually horizontal and vertical? Do I have any distracting bits and pieces poking into the borders of the frame? Do any of the main elements overlap or touch? And finally, is there anything I can do to clean up the composition? With these four questions addressed before you shoot at 10 frames a second, you will not only save valuable time, but you will end up with images that you are much happier with. This will give your brain time to linger and enjoy your artwork!

Another great article. I think I will be saving them to my phone so I can always have them for reference.

I’m really glad you’re enjoying my articles, Kwesi! Thank you so much for taking the time to comment. Stay tuned for more!

The ‘Keystoning Effect” & its correction by keeping the camera back parallel to the building vertical line, is the point that I liked most in this fantastic article. All the other points too ‘brushed up’ my basics once again ,reminding me like an alarm. Actually when we shoot, we often forget these simple factors in hurry….& Elizabeth’s Article just will help me to ‘stick’ to these basic points next time when I shoot . Thanks Elizabeth for the article. Expecting many more to come….!

I’m so glad you liked the article Ranjan. Thanks so much for taking the time to comment. And yes, there will be more articles to come!

Until today, the most difficult part of photography to me is COMPOSITION. No matter how many books, articles, magazines or websites that I’ve visited it’s still challenging and it’s even more challenging when you’re photographing landscapes. IMO, to get a good composition you’ve to be patient. Very patient. You’ve to pause and think before you click the shutter. You’ve to pretend that your DSLR is a film SLR (OK you can’t pretend that it’s film SLR). Take the shot, show it to someone and ask for their C and C’s. After that, take the same shot again this time after considering the C and C’s and try to improve.

There’re people who’re talented that they will produce good pictures everytime but most average Joe’s have to learn the basic and keep on practicing to produce good images.

Thanks for sharing Elizabeth.

Thank you for your comment Remi! I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

Great article Elizabeth. Very nice tips that are easy o follow. You seem to be a very good teacher. You should perhaps write a book on this topic. I think it will be an enjoyable read and will be very helpful for photographers. Thanks for this article.

Thank you so much Muhammad! Photography and teaching are my passion. I feel so lucky to be able to do both for PL.

Are these tips only for the landscape photographers?

No, these ideas can be put into practice for all kinds of photographic subjects and genres. Thanks for commenting.

Thanks for a very good article, Elizabeth. Love the before and after images, as they really help tell the story. I found that when I was using a camera without 100% viewfinder coverage I was always getting those little distracting elements at the edge of the frame, because I never saw them until I had the images displayed on my computer. Once I got a dslr with a full coverage viewfinder my post time to clone and crop dropped significantly.

I also suffer from consistently slightly tilting the image, so now I have been using the viewfinder level display in the Nikon D810 and that has improved my keeper rate as well. Sometimes those minor features in a camera, if used correctly can help you get it right in camera and save lots of post time.

Thanks for the comments Ned! Unfortunately, if you do not have full coverage in your viewfinder, it is much harder to avoid the border intruders! It sounds like you are having much better luck with your D810! Saving post processing time can be a real advantage if you have a lot of images to go through!

I practice this 4 techniques quite often. Thanks for reminding me them.

Good article.

You are welcome!

Wow! What an awesome article. It certainly opened my eye to slow down & really look & see what your camera will “really see” This article is another “refer to fav’s”!

Marg, thank you so much for your kind comment. I am so glad you enjoyed the article!

Excellent questions to be addressed in photography. Thank you for concise and clear article.

Thank you Assadi, and you are welcome!

Great article.

As to apparent distortion — that leaning look that comes with wide angle shooting — don’t forget Photoshop’s powerful Transform tool. Take, for instance, your golden building shot. With Transform you could, if you wanted, straighten the building at the expense of the sky on each side rather than the bottom material. You could also remove the slight kilter on its left side only (in the corrected shot).

Or that the red whateveritis against the cyan wall. The wall edge on the right is vertical, but the red whatsis is tilted leftward. You can correct that in Transform, at the expense of losing some of the cyan wall on its left.

Thanks for your comments Yandoodan. You are right, Photoshops transform tool is very powerful. However, it will cause some softening of the image if the corners are pulled out too much. As a general rule, you should pull the top corners out at the same time, and by about the same amount as you push the bottom corners in. However, this leads back to the same issue with loosing information in the corners. Depending on how drastic the correction is, you can sometimes get away with just pulling out the top corners. Another thing you will notice when you do this, is that the building may need to be “pulled up” as well, in order to maintain the same width to height ratio of the original.

Since I was trying to keep this article simple, I did not want to get into different types of perspective corrections possible in post. Stay tuned for my next article, where I will address all those questions!