I’ve heard a lot of “hidden tips” for landscape photography over the years. Most of them weren’t helpful at all. But, along the way, I have collected a handful that really are useful — nuggets of wisdom that I still use today, and that I recommend to other photographers as often as possible. I’ve included the five most valuable hidden tips below. Perhaps you’ve heard some of these before, but I hope that at least a few of them will be completely new.

Table of Contents

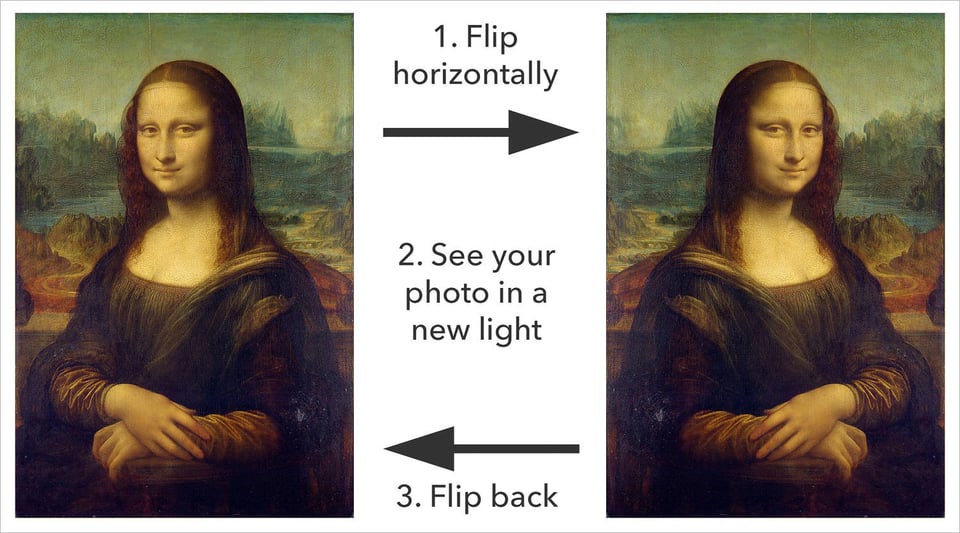

1) Flip your photos horizontally

I’ll start with the best tip first. That way, if it isn’t useful, you can skip this article and start reading something that will help you more.

It’s a simple trick: Flip your photos horizontally in post-production. Then, flip them right back.

Why would anyone do that? Nothing will change, except that you’ll briefly have a mirrored image. That doesn’t seem particularly helpful.

Interestingly enough, though, this is my favorite hidden tip of all. The reason? By flipping your photo horizontally, you see it in a different light.

Have you been editing a landscape photo for ages, and you can’t tell if your changes are actually improving it any more? Are you so familiar with an old photo that you’re having a hard time judging how good it really is? This tip will help you out.

When you flip your photos horizontally, it’s like looking at them again for the first time. Sometimes, you’ll like the photo far more than you expected — other times, you’ll realize that it isn’t as good as you thought. Or, you might notice new things that you need to edit, such as straightening the horizon or altering your crop.

No matter what, it’s an excellent tool to have for your own photography (and it’s easy to implement in nearly all post-processing software).

2) Capture the landscape doing something

Landscape photos are nice. Landscapes doing something are the photos that really leave an impression.

What do I mean by “doing something”? It’s a wide net. Maybe there’s a huge wave crashing ashore. Or, a rainbow forms during a dramatic storm. Either way, your landscape photos should tell the story of a moment in time — something happening that you were lucky enough to witness.

Here’s a photo of a landscape:

Here’s the same landscape doing something:

The final image.

Notice a difference?

The first photo isn’t bad. It’s a typical shot of a beautiful mountain valley; it shows how this scene normally looks. But it doesn’t tell a story.

The second photo is much better. It reveals a moment in time — the sun peeking over the Grand Teton mountains at the end of the day. I only saw the landscape like this for a few seconds, which is a large part of why this photo succeeds.

People don’t mind seeing landscape photos, but what they really want to see are pictures of a landscape doing something special.

Why are you capturing a particular photo? Is it because the view in front of your camera is simply beautiful? Or is it because you’re witnessing something unusual and spectacular?

Good landscape photos always have a reason to exist. They don’t show the world how just anyone could see it — they show the world doing something special.

Whether you capture a dramatic bolt of lightning, or a pristine landscape of fresh snow, your photos will be more powerful if they’re built on a story.

3) It’s about the process(ing)

I don’t like breaking the news, but most of the top landscape photos you’ll see have been heavily post-processed. In fact, without their processing, some may not even attract attention in the first place.

At some level, this makes sense. You can take a good photo under beautiful light of an incredible subject, and it won’t hold a candle to an identical photo with skilled post-processing.

However, the scary part for a lot of photographers is that some of the all-time best photos you’ll see are inventions of Photoshop rather than Mother Nature. As you would expect, this fact has sparked countless debates and arguments about what is acceptable in post-production, including lots of fierce statements from both sides.

And through everything, nothing really changes.

No, a photo’s value isn’t 100% based upon the post-processing behind it. In fact, some photographers today even refuse to manipulate their photos beyond brightness and color balance adjustments, and they still capture wonderful shots. Light, subject, and composition matter more than anything else, and they always will.

Still, even though you can capture good photos without extreme edits, it isn’t the norm for popular work today. If there is a “secret” of professional landscape photographers, it’s that almost all of them understand post-processing at a very deep level. And, as frustrating as it may sound, I recommend that you do the same.

Becoming an expert isn’t easy, but it’s worth the effort. If you’re good at post-processing, you’ll see a huge jump in the quality of your portfolio. No, it isn’t the most thrilling part of the job, but it’s a skill that really matters. It increases your attention to detail, and it lets you make the most of every photo you capture.

An unedited photo misses a lot of its potential — and there are plenty of other photographers out there who have mastered this game already.

Still, I recommend being subtle. You can draw a lot of quality out of an image without going overboard or looking unnatural. How much processing looks unnatural, and where should you draw the line? This is a decision you should make for yourself, and there are pros and cons either way.

4) Bookend your photos in the field

Have you ever taken a series of panoramas or HDRs in a row? If so, you probably know how tough it can be to remember which photos go together once you open them up on your computer.

There’s an easy trick to fix this problem: Bookend your important photos in the field, and you’ll save yourself a lot of time later!

What do I mean by that? All you have to do is take a photo of your hand before every series, and then another one at the end. Pretty easy.

This is a very quick way to mark where each set of photos stops and starts, saving some time and preventing headaches in post-processing. (Feel free to delete the photos of your hand once you’ve merged the proper images together, or labeled them some other way.)

There are other uses for the bookend trick, too, but this is the big one for landscape photography. Hopefully, if you hadn’t heard this tip before, you’ll find it valuable.

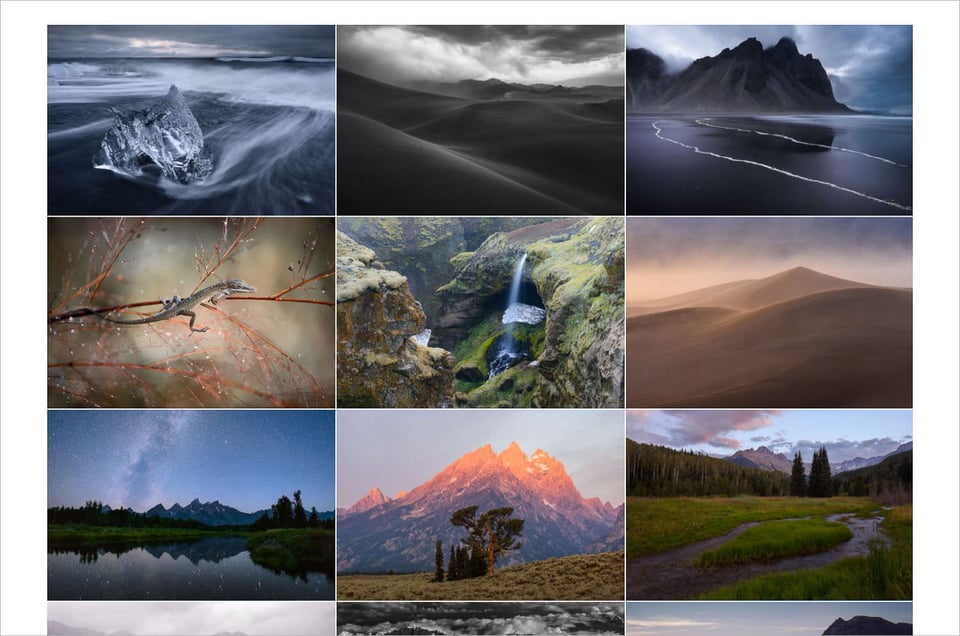

5) Show only your best

It’s a simple tip: If you only show your amazing photos, people will think that all your photos are amazing.

Ansel Adams said that twelve successful photos in a year is a good crop. To me, though, that seems like a pretty optimistic standard. I’d be happy with three or four truly successful photos each year. The years add up quickly.

Since starting photography, I’ve taken too many photos to count. Even as a landscape photographer, working more slowly and taking fewer images than other genres of photography, I still routinely capture a couple thousand photos during long expeditions.

How many photos do I display, though? A tiny, tiny fraction of that number. When I’m introducing people to my photos for the first time, I rarely display more than 75 images.

Consider, for example, what would happen if you made 5,000 smoothies over the course of a few years — and you only ever let anyone taste your best five. People would think you’re universally fantastic at making smoothies.

This holds just as true in photography. The fewer photos you display, the higher quality your portfolio is, on average. You get to be more selective.

In the end, you have the power to decide which photos to show the world. That’s a pretty powerful tool.

Conclusion

At least for now, these are the top hidden tips I know. As I find more, I’ll continue to update this article with new information, so stay tuned. In the mean time, feel free to test them out and see if they’re useful for your own photography.

Individually, none of these techniques will skyrocket the quality of your photographs. It takes patience and practice to learn a solid framework of landscape photography, and these tips are simply small parts of that larger whole.

No matter what, though, it’s always a good idea to expand your web of knowledge about landscape photography. You never know when a new tip might make a big difference for one of your photos. So, even if only one of these five suggestions is something you hadn’t heard before, I would consider it a success!

See Also:

- Five Landscape Photography Tips for Beginners (Five more tips, bringing the total to 10)

- Five Advanced Landscape Photography Tips (Now we’re at 15!)

I always bookend my panoramas by taking one photo of my hand, holding up a number of fingers equal to the number of shots in my panorama. Super simple, always works!

I’ll try flipping the phots. I never heard the bookend tip anywhere but I do bookend with photos of my feet.

Great tips guys! Photography is an art so it must be learned properly. A good guide can teach art in a great way. This article is similar to a guide because it is an eye-opener for blooming photographers and travel lovers.

Thank you so much!

Really big thanks from Mohit Bansal Chandigarh for sharing these tips. It’s really helpful as I am also a photographer so it will surely help me a lot.

This is incredible. Such an informative blog. Really big thanks from Mohit Bansal Chandigarh for sharing these tips.

These are incredible! I am a complete beginner in all of this, but I just got a new camera as a gift for my birthday, and I wasn’t thinking it wouldn’t hurt to learn a few tricks and use it from time to time to actually take nice pictures :) Thank you very much, your tips really helped! I am going to go practiceeee

Thank you Spenser! These tips were very helpful. These tips are things I’ve never read before, or would have thought on my own. I recently shot several panoramas. It was a nightmare figuring out where one panorama set of pictures ended and the next began. Love the bookend idea. Dan

You are quite welcome! Yes, bookending photos is something I’ve found to be very useful, just for the fact that it simplifies things for later. Best of luck putting these suggestions into practice.