Bird photography seems simple. You see a bird, you take its photo. But birds don’t just move – they can be in different environments and can have endless varieties of light shone upon them. All of a sudden, bird photography starts to get more complex.

And in some ways, it is. There’s so much I have to learn myself that I wonder if I’ll ever figure it all out. But there are also some really simple things that you can avoid and make your bird photos a lot better. Here, I’ll tell you about five of them.

Table of Contents

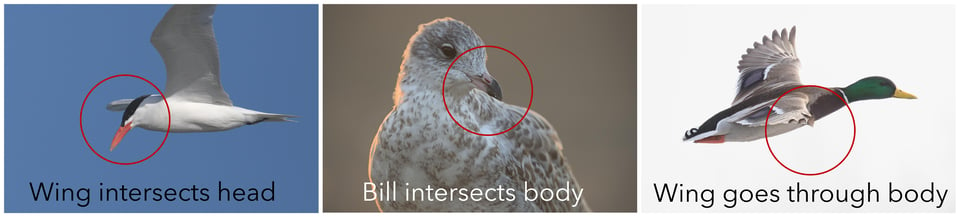

1. Self-Intersection

Birds have very flexible bodies and as a result, in some poses, their bodies produce strange self-intersections. Here are three examples:

The problem is that these contorted shapes take away from the recognizability of the bird form. Although there are some cases where intersections can be interesting if done deliberately – or minor enough not to be distracting – random intersections generally look confusing. So, one of the easiest things to improve in bird photography is pay attention to the form of the bird when composing in the viewfinder. Birds tend to move a lot, so it’s likely that a weird or contorted form will be replaced by a more recognizable form in the next minute.

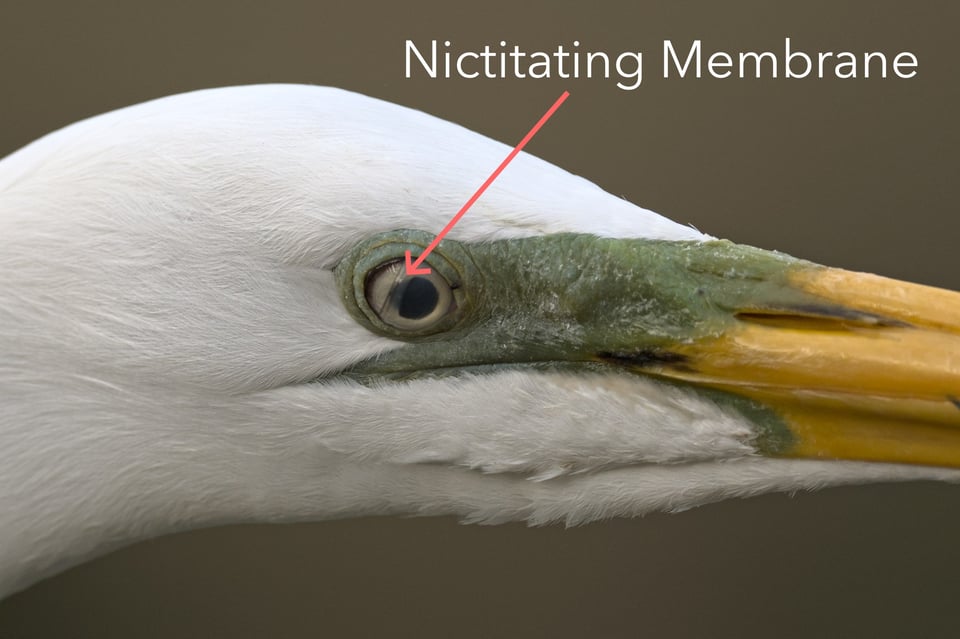

2. The Nictitating Mebrane

Birds have a translucent internal eyelid called the nictitating membrane. Actually, some other animals like sharks have it as well. Most mammals don’t have a fully developed nictitating membrane, except for some like beavers and polar bears. What’s it for? It protects the eye when the eye is likely to be in a risky situation, such as when a bird dives into water that is full of debris. Here is how it looks:

Unfortunately, when the eye of a bird is obscured by the nictitating membrane, it often looks strange. And even birds that are relatively still sometimes “blink their membrane.” So when you’re taking a shot of a bird, especially one which is doing something close to water, make sure your shot doesn’t have the nictitating membrane closed. When I see a bird like a heron or duck, I often take two shots of it roughly a second apart, just so I don’t get a shot with the nictitating membrane completely or partially closed.

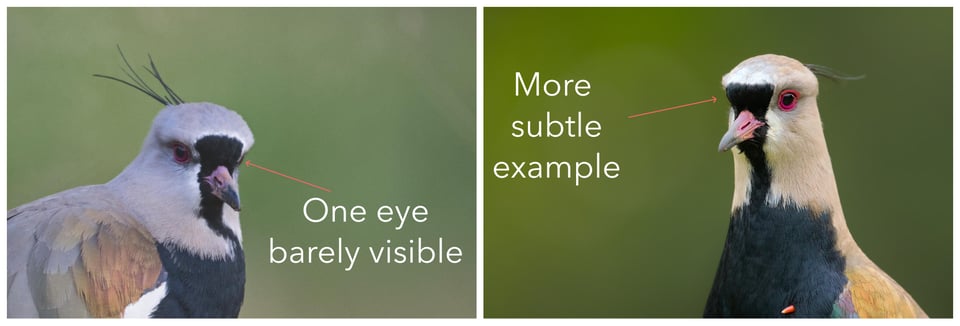

3. The Barely Visible Eye

Although this can happen with any sort of photography, including portrait photography of people, it’s a very common issue when photographing birds. It happens when one eye is hidden and the other is just barely visible:

The problem is again one of form, but I highlight it here because it is especially important. After all, people tend to go right to the eyes. When we see a barely visible eye, it often looks accidental, random, and confusing. So, try to include either one eye or both, but not half an eye. If you do notice a barely visible eye, it often just takes one step to the left or right, or waiting a moment for the bird to shift their head, to get rid of the problem.

4. The Disappearing Tail

Once you learn about this one, you just won’t be able to “unsee” it. It happens when a small bird is sitting on a think branch and its tail goes behind the branch:

The disappearing tail lends a break in the bird’s form. However, this one is a bit more subtle than the other problems. If the bird is in a more front-facing position rather than in silhouette view, then the effect is not so pronounced and might not be distracting. Or, if the bird is framed by a bunch of leaves in a pleasing way, then the lack of tail wouldn’t be distracting.

But, if the rest of the bird is clearly visible and the tail suddenly and abruptly vanishes, you may have a problem. So, this thing to “avoid” is more of a guideline: look for the key body parts like head, bill, tail, wing, and see if they are disrupted, and understand how that disruption contributes to – or detracts from – the overall message.

5. The Out-of-Focus Straight Line

The out-of-focus straight line happens when you’ve got an otherwise smooth background and there are a few areas in it with a bright strands of grass. It looks like this:

Of course, out-of-focus grass is not a huge problem in some shots, especially when its soft and produces a pattern. But when you’ve got some errant strands that make very distinct lines in the background, they tend to be distracting. Indeed, imagine you are painting such a scene. You’ve got a nice bird on a soft background. This out-of-focus line is akin to taking a big glob of paint and smearing it on the background. Why would you do that?

The best thing to do is avoid them in the first place. When you get to potential shooting areas, look for distracting out-of-focus lines. Check for them in the viewfinder when you’re shooting. Send the FBI after them if you must. Avoid them like the plague. Trust me, your shots will look a lot better without them.

In certain occasions, it’s possible to reduce their emphasis with post-processing. But it’s not easy, and it only works if they are already on the dim side. In any case, it’s one of the first things I look out for when I’m out in the field, and not too hard to avoid with practice.

Conclusion

The best part about photography is the creative process that can lead you into a journey of self-discovery. On that journey, there are also just some basic guidelines that can make your photos more effective, and I hope the five I’ve discussed today help improve your photography. They are not absolute rules, but rather good guidelines that follow from the more general principle of being deliberate and thoughtful in photography.

Do you have anything else that you always look out for and avoid in wildlife photography? Let me know in the comments!

Great article!! Love that us birders are getting some attention. I’ve never known the name of eyelid nictitaing thing, it’s ruined many good photos for me over the years!!

One more tip I want to add that may be so obvious that it doesn’t belong. When shooting birds, do everything in your power to avoid an all blue sky BG.

The only my time I actuate now on sky only BG is for ID purposes. I wouldn’t dream of selling or even showing a blue sky only BG shot. Why? They’re boring. Anyone can get a bird flying in the sky, getting them (esp. in flight) with an interesting BG is a challenge and it makes the photos better.

There are, of course, exceptions (like all rules in this article) but they are few and far between here.

Yes, I agree, many times, a plain blue background is not so interesting. I can imagine a few exceptions, but it does present some difficulties: for example, the overpowering blue needs the right colors, and it you plan on black and white it needs some interesting patterns.

Somehow, I always have difficulties to understand how to use that sort of advice. Is that supposed to help with image selection, suppose you have a lot of images to choose from?

Because I’m completely incompetent at persuading a bird to do what i want. Appeals like “Please, show me your tail” or “Please move to another background without distracting vertical lines” are usually ignored. Most of the time, I’m happy if I can get a few pictures before they disappear and if I’m lucky, a few are in focus.

Its “Beggars can’t be choosers” for me most of the time ;-).

Well, points 1-3 are mostly about taking enough shots to have a good selection and then thinking about these things when culling your images.

Points 4-5 are to consider in the field. Sometimes you can do something about it (like changing your position or waiting for the bird to take another pose), other times it won’t be possible.

The problem today is that cameras have become so good and fast, that you can shoot tens of pictures in seconds to minutes that many must be perfect. However, showing an animal as it is is no longer acceptable.

How do we know a bird has an extra eye lid when it is forbidden to show? And all this background that looks similar in out of focus, except blue as a blue sky can’t be.

Take your pictures as you like them, because those that don’t follow rules are often those that win prices.

This seems like a bit of a simplification to me. Photography in all genres always involves a bit of selective composition and choosing the right light. If someone said, “don’t take a picture of a person when their eyes are half closed and with a goofy expression on their face”, would you say that “taking a picture of a person as they area is no longer acceptable”?

No, it’s supposed to help with taking the picture when you think the composition is good. If a bird you see never gets in a pleasing composition, simply don’t take it (except for ID shots). It’s not about persuading a bird, it’s about waiting, finding the right environment, the right light, and waiting some more…like all photography.

Quite a few times when I go out to the field, I don’t get a single shot that I like. That’s just bird photography…but if you spend hours out there, you probably will. And another thing is that you have to slowly learn habitats, ecosystems, when birds are more calm, etc. Some places just don’t get good shots, while others do. It’s just a matter of learning that.

” … simply don’t take it” is no option for me, I’m not an artist. For me, the bird is more important than the pictures. I want to see feathers, not background and I don’t care about “composition” or whatever. There are quite a few birds that are rare enough to not give you a second chance. But, of course, everybody has different priorities and that’s good!

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with taking shots of birds to observe them more closely. In that case, the camera functions more like the microscope to observe the natural world. It’s a good use of it, too. But my post was about those who are concerned with the artistic aspect of bird photography.

Great read. We need more such articles on bird photography as it’s important for the community of bird photographers to share their philosophies and tips to their fellow photographers which have incremental value additions to this difficult genre of photography. These are issues after you achieve technical mastery. Small birds at a greater distance in a water body is another absolutely frustrating experience which I often look out for a try to avoid! Thanks

Indeed, smaller birds on a body of water are tricky. Often using a watercraft helps for those.

Great read. Thanks! I’ve taken some shot with the Nictitating Mebrane over the eye and your tip was really helpful to avoid that.

Helpful and interesting.

Trouble is, I’m now reluctant to go and take a more informed look at my favourite bird photos … especially the ones I’ve framed. My sparrowhawk has a lovely pale green backdrop (not bad for a 300/f4D + 1.4 TC on a D7500) but half an eye.

I tend to leave my D500 on HC and take a few frames of every still shot just in case there is a blink (or similar).

Half an eye isn’t always so bad and if the rest of the composition is really nice, then it might not matter. It also depends on how strange the almost-no-eye looks…

The nictitating membrane looks particularly dorky on birds (especially woodpeckers) when it’s “in-between” open and closed. But I do have some shots where the eye is completely obscured and it adds to the photo. Every rule can be broken if you know what you’re doing!

Indeed, that is true. If the woodpecker is in action, then the nictitating membrane can add to the dynamism of the scene! Good example!!

I can not understand the word FBI, sorry for my ignorance.

The police (federal bureau of investigation).

Haha, sorry, that was meant to be a joke.

I would not consider the out-offocus straight lines to be easy to avoid. Many if not most birds spend the majority of their life perched on/in vegetation, primarily on branches, which are inherently linear and usually not in focus. I have been tempted but have not yet bought into the idea that birds should appear on creamy smooth unnatural backgrounds. I prefer the genuine, even with the distractions. I would recommend avoiding the creamy smooth unnatural surroundings that make the photograph look like a painting, except where the bird is naturally isolated from the surroundings and background.

However, I agree with your points 2,3, 4, and even 1 with some exceptions.

I probably should have discussed more about that. In no way do I think out of focus branches are a bad thing, nor even grass in general. It’s more along the lines of very CLOSE grass that is unusually bright and disrupts backgrounds. You can easily get birds on branches and in vegetation that don’t have this serious problem.

With dragonflies this problem is even worse than with many birds. Their habitat often has straight lines in the background from reeds or tall grasses and many species are only present or active in sunny conditions which makes the OOF lines even more distracting. Creamy smooth backgrounds mostly happen with the subject in a spot that they would usually avoid because it makes them stand out for predators. It’s definitely something to watch out for but difficult to avoid, especially when the subject is flying and you have even less background control.

Longer lenses will help to control the background but in my area I often cannot get a clear shot with those due to foreground foliage. Sometimes it helps to use a different lens e.g. my Canon 100L macro tends to emphasize OOF lines and other contrasty details while my 2.8/200L is much more forgiving in similar conditions thanks to different bokeh.

Excellent read. Here are five more easy-ish things to avoid:

– Much brighter backgrounds than the bird, especially direct sunlight behind a shaded bird

– Partial shadows on a sunlit bird, especially from thin branches

– Forgetting to fix strong color casts (esp. strong green and/or blue) on the RAW in post. Don’t just white-balance adjust against the offending color; combine that adjustment with selective color desaturation.

– Shooting a stationary bird from a low position (belly shots). Useful for documentary shots only.

– There is a special case of #5 that I call the double-branch bokeh. This happens when you get two identical and parallel out of focus lines as a result of the same branch in the background, and I mostly see it with long focal lengths and smaller apertures (>6.3). Massively distracting and their appearance usually results in deletion, even if the rest of the image looks good.

Sorry for my fourth point I should have specifically referred to birds that are stationary in very high positions above the shooter. Getting as low as possible for birds that are in water or on the shore is, of course, the best position in most of those cases.

Very good points!

I agree with most points, except for the first (at least not fully). While you are generally right that bright backgrounds aren’t ideal, you can still get great shots in such situations (and it can even be an artistic choice). But you need to pay extra attention to lighting and composition, and it also requires careful (and not overdone!) post-processing.