As photographers, it’s easy to get in our own heads and overthink which aperture to use. On one hand, there’s the classic saying – “f/8 and be there.” On the other, modern lens reviews almost always conclude that the sharpest aperture is around f/4 or f/5.6.

But what aperture does no one seem to like, and certainly not recommend that you use if you can help it? f/16.

Review after review shows pitiful lens performance at f/16, often worse than wide open. The farthest any self-respecting photographer would dare to go is f/11, or so says the popular wisdom.

Adding to this perception is the fact that many lenses max out (min out?) at f/16. When you reach that aperture, you get the sense that Nikon and Canon are park rangers grabbing you by the shoulder and saying, “Whoa, that’s far enough, buddy,” as you approach the edge of a cliff.

If you’re wondering why f/16 gets a bad rap, it’s not hard to explain. Diffraction is high at that aperture – light waves bending and interfering with one another as they pass through your aperture – meaning that photos at f/16 just aren’t as sharp as they can be.

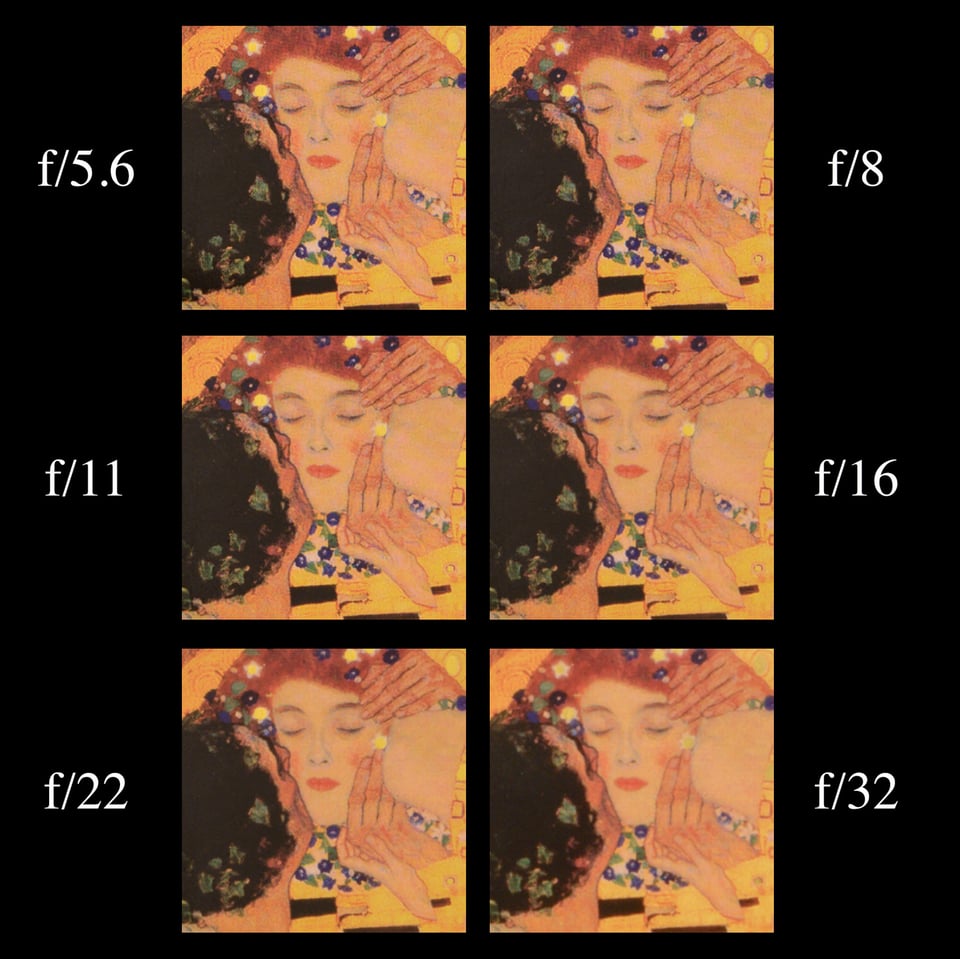

This diagram shows the levels of diffraction you can expect at various apertures, all the way to an unreasonable f/32 (click to see the differences more clearly):

Personally, I love f/16. (Though I’m speaking as a full-frame camera user; divide 16 by your crop factor to get the equivalent for your camera system.)

I’ve written reviews for Photography Life where I talk about a lens’s sharpness getting worse by f/11 and especially f/16. Yet every time I write something like that, I start grinning maniacally and whispering excellent like Mr. Burns.

Why? Because those apertures are where I’m planning to make my last stand – loss of sharpness be damned.

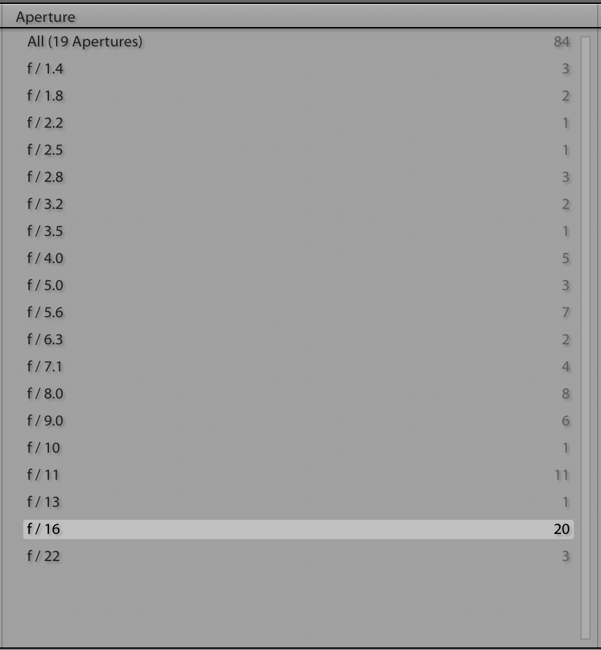

Case in point: My “best-of” collection in Lightroom currently has 84 photos. I took 20 of them at f/16, the most of any aperture. Second most is f/11, where I’ve taken 11 of my favorite photos.

Of course, I’m a landscape photographer, so this skews the numbers quite a bit. If you’re a documentary or portrait photographer, this article probably isn’t for you. Stick with f/2.8 or whatever aperture you prefer. Then pat yourself on the back for avoiding any significant sharpness loss from diffraction.

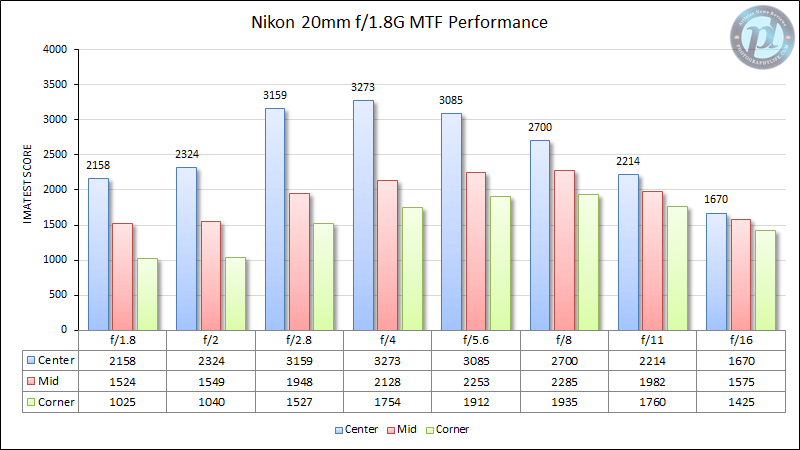

That said, how much sharpness loss are we really talking about with f/16? To put things into perspective, take a look at the following lens chart. It’s from the Nikon 20mm f/1.8G, a sharp lens that’s popular among landscape photographers:

As you can see, center sharpness on this lens is the worst at f/16. Sharpness in the corner is only a tad better; f/16 beats the numbers at f/1.8 and f/2, but it’s worse than everything from f/2.8 and beyond.

It doesn’t seem like there are many redeeming features to f/16. But that’s missing a couple important points.

For one, don’t just pay attention to maximum sharpness numbers. Pay attention to sharpness consistency across the frame – the difference between center and corner sharpness. By that measure, although f/2.8 is sharper overall than f/16, it’s not a great aperture to use; the disparity between center and corner sharpness is just too large – probably enough to stand out to a discerning viewer.

Instead, the best aperture on the Nikon 20mm f/1.8, taking both consistency and overall sharpness into account, is arguably f/8 – even though center sharpness is higher at three other apertures. You might argue that f/5.6 is a better aperture overall, and that’s true in total numbers, but the extra sharpness in the center of the frame at f/5.6 is not necessarily preferable if it makes the corners visibly worse by comparison.

Admittedly, though – even by a generous definition – f/16 is a step down in image quality from most of the other apertures. But that doesn’t mean you should avoid it. Aside from its excellent consistency from corner to corner, f/16 is worth using because of one important reason: depth of field.

Let’s say you want maximum foreground and background sharpness in a photo you take with the Nikon 20mm f/1.8. You’re focused 6 feet / 2 meters away, and the nearest object in your photo is 3 feet / 1 meter away (because you followed the double the distance method optimally).

I think you’ll agree that this is a pretty reasonable situation – certainly not an “extreme” scene where you’re focused on something that’s almost touching your lens. But in this scenario, which aperture should you use to maximize foreground and background sharpness?

Too wide an aperture loses sharpness because there’s not enough depth of field, while too narrow an aperture cancels out the increased depth of field by adding too much diffraction. Mathematically, though, there is an answer – and in this case, it’s f/13 (derivation in this article).

That’s a lot smaller than most people would think. A 20mm lens has a lot of depth of field compared to longer lenses, and focusing six feet away isn’t exactly crazytown. Yet, to maximize foreground and background sharpness, f/13 is indeed the way to go.

If your answer in this case is “f/8 and be there,” you’d lose about 17% of the maximum possible sharpness in both the foreground and background. If your answer, instead, is “f/16 and be there,” you’d only lose about 5% (calculated using George Douvos’s charts here).

The calculation shifts even more in favor of f/16 as you use longer and longer lenses. 20mm is pretty clearly a wide angle, which gives it some extra depth of field. But what if you wanted to use a 35mm lens instead – also a popular choice for landscape photography?

With that focal length, f/16 is optimal when you’re focused a very typical 12 feet away (3.7 meters). And it’s not far from optimal even if you’re focused on something that’s a whopping 20 feet away – only a 7% loss of sharpness versus the ideal aperture of f/12.

A lot of photographers will use a 35mm lens for landscape photography and casually pick f/8 or so, thinking they’re getting a lot of sharpness. But unless you’re focused 50 feet away or more (15 meters), f/8 doesn’t get you the sharpest photos. A smaller aperture does instead.

That’s why f/16 is so great.

Often, photographers don’t realize just how little depth of field they can get at f/4, f/5.6, or even f/8. I’ve seen plenty of photographers get blurry corners even at the supposed “sharpest” aperture on their lens. The reason? The lens isn’t blurry at that aperture. Their corners are just out of focus.

I’m not saying that f/16 is a sharp aperture in and of itself. It’s not. But if you’re photographing a three-dimensional scene, and you want good definition from front to back, it’s very often (I’d even say most of the time) a better aperture than f/4 or f/5.6 – even if it doesn’t score as well on a flat test chart.

A photo taken with good technique at f/16 still has pretty wicked sharpness. Sure, there’s diffraction, but it’s not bad enough to ruin a photo. (If your photo is too blurry to print large at f/16, it’s not diffraction that caused the problem.) Focusing errors and motion blur are, by far, the more likely culprits when your photo isn’t sharp.

Indeed, if focusing errors are what plague you, f/16 can actually help your sharpness. All that extra depth of field smooths out focusing errors (and some lens issues like field curvature) to make for better results than you’d otherwise get. In a way, it minimizes the chances that something can go wrong in your landscape photo.

That said, I definitely don’t recommend using f/16 as your default. I don’t recommend using any aperture as your default, because the best aperture changes wildly from scene to scene (and if maximum sharpness is your main priority, you’ll usually be focus stacking anyway). If I did have to pick just a single “best” aperture for daytime landscape work, I’d probably lean f/11 rather than f/16 anyway.

But the horrors of f/16 are way overblown. If your foreground is close to your lens, or you’re shooting landscapes with a telephoto, small apertures will improve your image quality far more than they harm it.

So, the next time that you see warning signs about the impending sharpness abyss, tell your lens company that you know better and walk right up to the edge. The photos you capture will be worth it.

Thank you sir. Good points for f16 in certain situations. I’ve been doing this for decades. I do, however, find that not going beyond f13 has worked better, but have used f16 many times, especially in the film days, ah, that would be even today I guess. Thanks again.

Great article spencer and you just made a compelling argument for focus stacking.

Thanks Spencer – great article and really useful. Interesting to read some of the commentary and the attempts to apply physics. The message you have given me, Spencer is when DOF is important don’t be frightened of F16 although F12, or F13 may be even better. I used to always try to use F16 approximately for landscapes or even F22, but was turned off it a bit by soothsayers of doom on a Fuji forum. I tried arguing with them, but ultimately deferred to their greater ‘wisdom.’ But your message to use F16 or so and blow diffraction (my interpretation here) is very reassuring. Thank you.

Good article. I think the key is to willingly use the aperture you need – f/16 or even f/22 – but understand the tradeoffs and don’t lock into a single aperture.

DxOMark shows the Nikon 24-70 f/2.8 ED is pretty good at f/11, but drops off sharply at all apertures at f/22. As a practical matter, this means I’m only using f/16 to f/22 when it is absolutely necessary. My normal apertures are f/9 to f/13 for landscapes. If my closest element that I want is 50 feet away, I can comfortably use f/8, but if it’s 4-5 feet away, I need to give a lot more thought to aperture, DOF, and focus target.

Where I get concerned is when I see photographers starting at f/16 when it is clearly not necessary to “maximize DOF” when it would have been maximized at f/8 or so. Some of these same people are focusing in the center of their image rather than an appropriate near target to optimize DOF.

Very good article Spencer thanks ! I may add that f/16 is also very useful for adding some starburst effect to the picture if the sun is in the frame (or artificial sources of light at night), although some lenses do not need to be stopped down so much for that.

Hello,

First of all thank you for this article. I am by no means an expert but I know what I like and I liked f/16 in your examples above. In fact, I’d go so far as to say I liked it better than any of the other stops. Maybe it’s my 68 year old eyes or maybe its my laptop screen, (Samsung 13″ Notebook9pro) which I think is pretty good. When I worked primarily as a studio photographer I almost never used any aperture below f/11. I found most clients preferred NOT to have an ultra-sharp image. Now that I don’t shoot studio much and primarily shoot landscape and wildlife, I find that I still primarily shoot at between f/11 and f/16 unless I’m shooting macro of course. Shooting wildlife I’m primarily at very long focal lengths so shooting below f/11 just isn’t good. I think too your comparison of the overall image as opposed to just the center is a very valid and important point. I tend print my favorite images and viewing prints as opposed to viewing digitally is a very different thing. IMO, shooting at large apertures is way overblown unless you’re shooting in bad light or trying to get NO depth field at all. I have a hard time understanding photographers who say they have to use f/4 and below yet want to hand hold. What’s up with that?

It is a little marginal anyway, the difference between F8 and F16, if you are only looking at resolution. Truth be told, if you shoot raw and post process, a tiny touch of de-haze, clarify, and sharpening pretty much eliminates the differences anyway. I go on to use Nik Software define filter and that really does work a treat on detailed shots, fishing boats close up etc, with all the equipment and chandelery on the boats.

Some subjects simply don’t work with a shallow depth of field, and I have found at f16 the quality is more than enough in most cases. Tricky light can make it harder to draw out the best from an image but if you need the depth of field, then you need f16. To be honest I have never really thought if it as being off limits, in fact I’ve never really noticed a perceptual image quality difference, though endless lens tests will tell you that the difference exists. I speak as a full frame raw shooter – smaller formats probably show the difference a little more. The interesing thing I found here is that after reading the article, I went an checked the reviews / tests for the lenses I use, and sure enough, when it comes to f16, the image quality difference between corner and centre sharpness is much less than with the lens opened up to f8 or bigger. At those apertures. all my lenses display a wider image resolution difference between corner and centre.

That is very interesting – when it come to post processing, if the sharpness is more uniform across the image, making changes to sharpness on the computer should prevent us accidentally having an oversharpened centre in order to get the corners as we want!

Very thought provoking, off out in the morning to garner some images just to see what I get accross the aperture range and depth of field. Thanks Spencer, we forget stuff like this, its useful to know it.

If I recall my highschool physics correctly, diffraction occurs most strongly as the size of the apergure approaches the wavelenght of light. Since the diameter of the the aperture (d) is related to the f number (n) as

n= f/d the same f number has a larger aperture diameter in a lens with a longer focal length.

f/16 in a 20 mm lens would represent a diameter of 20 mm/16 or or 2.25 mm.

on a 200 mm lens the diameter would be

200 mm/16 or 22.5 mm. Tome it seems that diffraction in the latter case is negligible. The wavelength of blue light is about 400 nm or 0.000 4 mm. Since this is much smaller than even the small 2.5 mm aperture of the 20 mm lens at f/16, I don’t think the diffraction by the smaller apertures is really the issue. I think soething else is going on.

Diffraction may also occur as light passes a single edge. I suspect the smaller apertures just dim the image light enough that this diffracted light becomes significant.if that is the case then this diffraction is there at all aperrures. I don’t think I ever heard about diffraction being mentioned in lenses in the days of film photography. Am I missing something?

Brian,

See the fifth paragraph of the article, which starts “If you’re wondering why f/16 gets a bad rap…”. Its second sentence starts with the word “Diffraction”, which is rendered in blue text to indicate that it is a hyperlink. This hyperlink is to the article What Is Lens Diffraction? by Spencer Cox.

photographylife.com/what-…hotography

I suggest you read it, along with its comment thread started by Simon on APRIL 4, 2016 AT 9:20 AM, in which I have explained the effect of focal length on the diffraction induced by an aperture diaphragm.

If you have any further questions, by all means ask.

Hi Spencer

you are right for MTF, but as other reader noted before you must take into account pixel size (airy disk).

In such a case you are losing resolution, in other words you are oversampling the lens resolution, in such a case above nyquist (communication theory) you are storing unuseful data.

I do not say that using f16 is wrong, just saying you are converting a 42mp camera in a small mp count, and using raw you are storing in such a way irrelevant info.

It is true that the more resolution improves the system MTF (acoording to a Zeiss paper).

I think it is not an easy task to select f stop.

In the beginning of digital camera era sensor was the limit for useful mp, today as sensor mp increases the lens is the low pass filter, and in such a way if you use f16 you are turning your state of the art camera in an old D700.

but good point it about overall resolution, interesting how much it varies with f stop

Great point! Lloyd Chambers has extensively tested the A7Riv and has shown that for the A7Riv (3.74 micron photo sites) with excellent lenses, stopping down beyond f/4.5 will result in steady increasing dulling of micro contrast. He suggests f/5.6 as the practical limit. He also points out that while diffraction mitigation sharpening can help up to a point, it never improves tonality.

Thus, the recommendation to use high f-stops for greater depth of field with high megapixel cameras will result in disappointing results.

I just received my A7Riv yesterday, and I suspect I will be using focus stacking more than I have in the past. Unfortunately, Sony doesn’t have an in-camera feature that facilitates focus stacking like the Fuji X-T3 does.

Hi Jack, there are a few important misunderstandings/misinterpretations in the past few comments that I will try to clear up.

First, diffraction is not a function of pixel size. A lens at a given aperture will project the same size Airy disk (diffraction blur) regardless of the pixel size or pixel density of your sensor. As a result, the optimal f-stop (in terms of balancing diffraction/DoF) does not change regardless of your pixel density. Instead, your goal should be to optimize the sharpness of the projection from your lens onto your sensor, because that’s how you maximize total photo sharpness regardless of your sensor.

What is true is that camera manufacturers’ cramming more and more pixels into a sensor becomes less useful when you’re at small apertures. In other words, this is not an argument against using something like f/16 on a high-resolution sensor – more an argument against camera manufacturers continuing the megapixel race beyond the point where it matters. But it is still beneficial to use higher resolution sensors at small apertures (or, at worst, with insanely small apertures like f/45, not harmful).

That’s what Lloyd was measuring – the point at which it became less useful for Sony to have crammed in so many pixels on the A7r IV, because diffraction blur minimizes those gains.

But what I want to be clear about is that there are still many cases where the sharpest possible aperture when using the A7r IV is smaller than f/5.6. What would you do if you have a landscape with a nearby foreground, but you can’t focus stack? Using f/5.6 would be a really bad idea, because the extreme out-of-focus blur (circle of confusion size) in the foreground will far outweigh the slightly larger Airy disk from using a smaller aperture.

And sure, in that case, it might not matter whether your camera had 61 megapixels or 24. But no matter what settings you use at that point, 24 megapixels (for example) would be your limit. Using a wider aperture will indeed give you a sharper result on your focus point, but the depth of field you lose will make the foreground and background equivalent to shooting with – for example – a 12 megapixel camera.

Of course, focus stacking or tilt-shift lenses are the optimal answer to make the most of 61 megapixels. Or just photographing only landscapes where everything is at infinity. But for most photographers, those solutions are only possible in a small number of scenes.

1. what could be a reason to not be able to focus stack in a rather calm landscape? I get it that brushing out unsharp parts when leaves are moving in the wind can be time consuming. So it really depends on the picture wether I want to bring in this effort or not – and I cannot tell in the beginning, as wind or water movements bring in a random factor.

2. and what’s the result of f/16? At low ISO? a long shutter speeds? There also can be motion blur due to long exposure times. So, there’s a quality loss due to diffraction, to possible tripod movement and to possible subject movement. This can look very artistically but it also can worsen the picture.

3. it’s easy to get DoF with wide or wider angles. But zooming in, you face the same troubles. And the longer the focal length gets the more obvious it becomes that there’s no DoF from distance X to Y all very sharp, but seeing more like a gradient from focus center to less focussed regions. So it’s all about balance of “acceptable sharpness”. If I want sharpness form point A to B, I simply HAVE to focusstack. f/16 or smaller is second best, by a huge margin.

4. I’m very aware that focus stacking doesn’t work well in something like your first sample picture – but here you were already going for a blurry motion effect, so diffraction simply doesn’t matter.

Hi Spencer

I think you misunderstood my comment

as you said airy disk is mathematical, it depend on physics.

the variable is pixel size, my point is that if airy disk covers (as an example 4×4=16 monochrome pixels) pixels, then you are oversampling and as you said turning your high mp pixel camera in a lower mp camera.

but photography is not a set of not unbroken rules, otherwise all pictures would look the same

in addition what Zeiss states is that the oversampling increases the MTF of the overall system (lens + sensor)

and as with all things in our lives we must take into account what we got in addition and what we loss

perhaps this issue is too complex to be treated superficially, it needs tons of mathematics, physics, optics, and common sense

It is true that diffraction is more noticeable with higher pixel densities, the same with a shallow depth of field–not because the diffraction is actually higher or the depth of field is actually shallower, but because you are zooming in more on the image with a higher resolution. Thus you need to be more discerning, particularly with hyperfocal distances. So you are both correct in a technical sense.

To determine where your pixel density will start becoming diffraction limited, you can use this formula:

Diffraction = native CoC of the sensor x 1000 ÷ (2nd airy disc x color wavelength [550nm] x 1,000,000)

In the case of my 46MP Nikon D850, the native CoC is 0.009mm. The constant for the 2nd airy disc is 2.43932 (diameter, so double the radius). 550 nanometers is the middle of the color spectrum of light that the human eye can see, so we’ll use 0.00000055 for the color wavelength (infrared or ultraviolet would have a different number). So if we simplify the above formula it looks like this for my D850:

0.009mm x 1000 ÷ (2.43932 x 0.00000055 x 1000000) = f/6.5.

While diffraction does start setting in at f/6.5, in practical use this can usually be doubled without compromising image quality too much, so f/13 is what I typically use on the D850 as the smallest aperture with large prints—if I can go wider like f/8 then I will of course. If I know I’m not going to be printing very large (like publishing to social media or websites), I’ll push it to f/16. But generally, I want the highest quality I can get from the camera, which limits how small an aperture I can use. My application is generally extremely large prints from stitched gigapans, so I have to be very critical.

Most of the above was taken from an article I wrote awhile back, the rest of the article is here: galleries.aaronpriestphoto.com/Artic…Print-Size

Hello Aaron

Where from could I get native CoC of D800e and 2nd Airy disc?

Thank you in advance!

Just to blow all your minds… An f/22 shot on a 50mp camera is sharper than an f/14 shot on a 24mp camera if both are sharpened correctly.

The reason is is that the 50mp shot over samples the image and alows the blurring at f/22 to be better reduced.

The big fallacy with all of these resolution figures is that they are a brick wall beyond which no finer detail exists. That’s bollocks. It just means that there are no finer details beyond an arbitrary level of contrast.

This means at f/22 there is more detail beyond the ‘diffraction limit’ but it’s low contrast. With a high resolution sensor and deconvolution sharpneing it’s surprising what you get back.

I’ve been using a 150mp back and shooting at f/22 and f/32 and they’re both useable although you do get lower contrast results that need more sharpening. The other thing is that you can see some differences beyond the supposed diffraction limit between bad and good lenses. That’s something for another time

It would habe been interesting to compare a focusstacked picture with a couple of f/5.6 shots against a single f/16 shot.

I guess, sharpness of the stack is better, visibly better. Focusstacking isn’t the only way ro reduce diffraction caused by (too) small apertures, tilt-shift lenses also allow a sharper yet wider DoF at moderate apertures. And if huge DoF is the target, smaller sensors have advantages – at least if one believes in the stuff the “equivalence gurus” tell us.

Surre, once there was a “group f/64″, aiming for loads of DoF – but they used 4×5″ or 8×10” “sensors” with a much lower resolution per square inch than today’s sensors.

The diffraction correction in Capture One brings a rather aggressive sharpening in some areas which look as kind of artefacts. I will not rely on it, to my taste it looks like a badly adjusted sharpening filter. After all, if one decides to go diffraction road, he or she should be aware that the information gone remains gone, no matter what AI fakes to fill the gaps.

But often not everything is about sharpness all over the place – the first sample picture basically only uses f/16 to soften the movements of the water. Correctly focused it would look as good with f/8 as the sky is distantly blurred by haze and the water structures by movement. To me not a good sample for need of DoF.