It seems like the debate of DX vs FX for wildlife and sports photography is a never ending one. DX shooters argue that they get more reach, stating that DX is like a “built-in 1.5x teleconverter”, or that DX setups are lighter due to smaller lenses and less expensive, or that DX chops off the corners of lenses, thus reducing vignetting and other optical issues. On the opposite side of the fence, FX shooters argue that they get better image quality at pixel level, better viewfinder, less diffraction issues, better AF performance in low-light, etc. Seems like we have two camps, each defending their own side for various reasons. Having spent a number of years shooting both DX and FX starting from the first generation Nikon FX cameras and every single DX camera manufactured by Nikon to date, and having talked to a number of other photographers that shoot for a living, I came to a conclusion that there are some myths surrounding the DX format that need to be debunked. In this article, I will provide my personal insight to this topic and explain why I believe that FX is always better for photographing sports and wildlife. This article evolved as a result of recent discussions of the subject with some of our readers.

Table of Contents

1) The Myth of the DX Built-in 1.5x Teleconverter

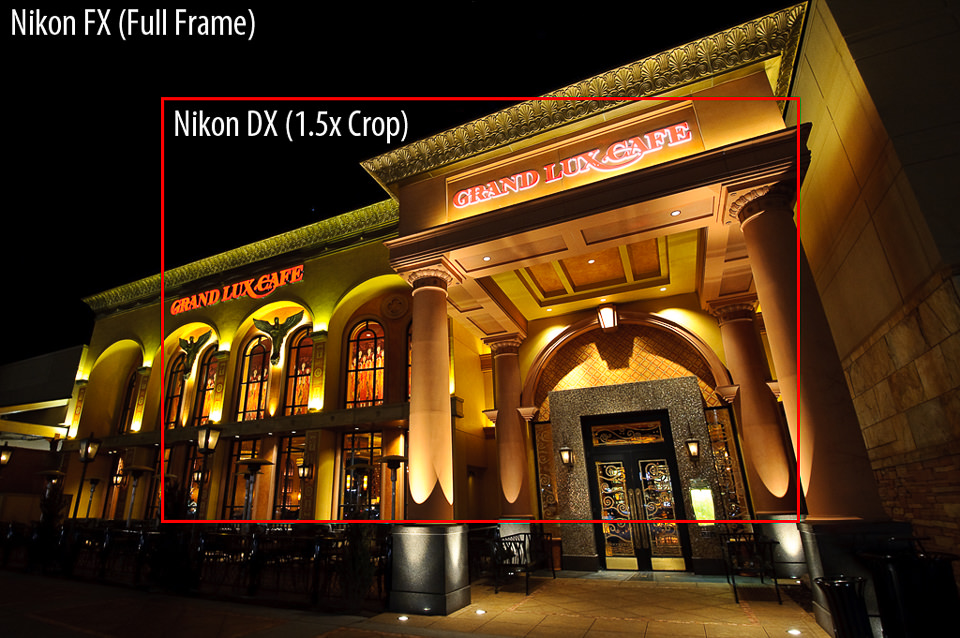

A lot of people seem to be very confused about the effect of a crop sensor on the focal length of a lens. Stating that a crop sensor increases the focal length of the lens or acts as a teleconverter is completely wrong, since focal length is an optical attribute of a lens and has nothing to do with the camera. I talked about this in detail in my “Equivalent Focal Length” article that I published a while ago. Simply put, a DX sensor can never change the optical parameters of a lens, so if you are shooting with a 300mm lens, it stays as a 300mm lens no matter what camera you mount it on. The confusion of “equivalent focal length” comes from manufacturers that initially wanted to make people understand that the field of view on a cropped sensor camera is tighter than 35mm, because the image corners get chopped off. The word “equivalent” is only relative to 35mm film. So you cannot say that your 300mm lens becomes a 450mm lens on a DX body. It does not and never will. All you are doing, is you are taking an image from a 300mm lens, cropping it in the center area and magnifying that center with increased resolution.

2) DX Pixel Size and Resolution

The only reason why some people thought that DX provided longer reach, was because DX sensors historically had similar resolution as FX. For example, both Nikon D300 (DX) and D700 (FX) have about the same resolution – 12 MP. So despite having sensors of completely different sizes, the two cameras produce images of similar size / resolution. Ultimately, this means that the D300 can resolve more detail from the center of the lens (which is typically the sharpest on any lens) and thus magnifies the subject more, which led people to believe that DX was better than FX to get closer to subjects. One aspect that was rarely talked about, however, was the fact that the D300 has a lot more noise than the D700 due to smaller pixel size. So despite having this magnification advantage, photographers had to constantly deal with cleaning up apparent noise even at relatively low ISO levels. I personally had to constantly down-sample images and clean them up via noise-reduction software to get rid of the artifacts visible at anything above ISO 800 (and noise was visible even at base ISO!). So at the end of the day, taking a DX image and down-sampling it aggressively, versus simply cropping an FX image produced somewhat similar results, with a slight advantage on DX that resulted in more detailed shots, thanks to the down-sampling process.

But these advantages pretty much went away with the D800. The Nikon D800 has a 36 MP sensor, which has the same pixel size as the Nikon D7000. In DX mode, the camera resolution is reduced to 15.4 MP, which is pretty close to the native resolution of 16.2 MP on the D7000. What this means, is that the Nikon D800 is capable of producing images of about the same detail as the Nikon D7000 at pixel level. Thus, the Nikon D800 can be thought of as a two-in-one camera – it can be both a D800 and a D7000 at the same time. I remember when the D800 came out, many DX users that wanted to move up to FX were extremely unhappy with it, because of its slow fps rate and small buffer. What they did not realize, was that the D800 actually produces images with less noise (newer sensor technology and better image processing pipeline) and at all ISO levels compared to the D300/D300s in DX mode and has a larger buffer in comparison. Here is the buffer capacity information that I grabbed from Nikon’s website:

Nikon D300s Buffer (NEF, Lossless Compressed, 12-bit): 18

Nikon D800 Buffer (NEF, Lossless Compressed, 12-bit): 38

Yup, the Nikon D800 can accommodate more than twice the number of images in the buffer in DX mode compared to the D300s. Now there is a difference in speed – the D300s is capable of shooting 7 fps compared to 5 fps on the D800 in DX mode, so the D300s is certainly faster. But for those that don’t particularly care for 2 fps speed advantage, the D800 sounds very appealing. It is not like we are talking about 5 fps vs 10 fps. Plus, with the added battery grip and a different power source, you can push the D800 to 6 fps in DX mode, which is good enough for most situations.

So let’s get back to increased magnification advantage of a DX sensor. The current Nikon D7100 has 24 MP of resolution, which, if we convert to full-frame would result in a 56 MP camera. That’s a lot of pixels, a whole lot more than D800’s 36 MP. The question becomes, is the glass you attach to the D7100 going to be capable of resolving that much detail? If it does, what happens when you attach a teleconverter on top of that (which degrades pixel-level sharpness)? The advantage of greater amount of detail on DX sensors is arguable – at pixel level, DX cameras are more demanding on optics, which is not always good, especially when using teleconverters. As I have pointed out in my “teleconverters” article, the Nikon TC-17E II and TC-20E III eat up quite a bit of resolution. At what point will the added resolution make no difference due to lens + TC combo not being able to provide enough details for such a high-end sensor? Nikon knows that they are pushing the limits, I suspect that it is one of the reasons why they are getting rid of that anti-aliasing filter now. If a Nikon D400 ever comes out, most likely it won’t sport an AA filter either.

Let me give you an example of what I mean here. Take the Nikon 200-400mm f/4G lens, for instance. While it does a great job with the TC-14E II, it just loses too much resolution when either the TC-17E II or the TC-20E III are mounted on it. It gets to the point where you start evaluating if it is better to just use the lens with the TC-14E II and crop, or use the TC-17E II / TC-20E III and down-sample. In my experience, due to the fact that TCs affect AF accuracy and speed, you are better off with the former than the latter, especially for photographing anything that moves. The same logic can be applied to high-resolution sensors. At what point does DX’s added megapixel advantage start wearing off when compared to FX?

If we take similar sensor resolution on both FX and DX (say 24 MP when comparing the D600 to the D7100), the D7100 will obviously offer greater amount of resolution in the cropped area than the D600 (assuming the image from the D600 was cropped to yield a similar field of view) – but that’s only true with three conditions: a) that the photographer had a good technique and did not introduce more blur due to high pixel density, b) ISO was in the lower range (generally below ISO 800-1600), where DX produces similar noise as FX at pixel level and c) the lens was good enough optically to be able to resolve the detail. The last condition is generally not an issue on pro-level super telephoto lenses, which can definitely resolve beyond 24 MP on DX, so it is mostly the question of technique and shooting at lower ISOs. But when shooting birds, for instance, what was the last time you shot at ISO 100? With shutter speeds typically above 1/1000, your typical range would be ISO 800-3200 and that’s where FX clearly has an advantage over DX (again, we are talking about pixel-level quality). So if you end up with an image on DX that has a lot more noise than on FX, you will often resort to down-sampling the image to reduce that noise.

In summary, the “reach” advantage of DX sensors is quite debatable. With the added noise, more visible effects of camera shake due to high resolution and other issues, I would not say that DX has a lot to offer when compared to FX.

3) The Impact of Diffraction

Smaller pixels magnify a lot of things and one of them is diffraction. DX sensors are typically impacted by diffraction at f/11 and smaller. While you might not notice diffraction issues at f/11 on the D300, you will surely notice them on the D7100. You will have to look closely, but the difference is there at 100% view and even more obvious as you stop down to f/16. The theoretical maximum diffraction limit on a pixel is about 4 microns and the D7100 is already at 3.9µ! So diffraction can be seen more on sensors with higher pixel pitch and DX has already pushed that limit.

Take a look at the following chart:

| Nikon DSLR | D300S | D7000 | D7100 | D600/D610 | D800 | D4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Resolution | 12.3 MP | 16.2 MP | 24.1 MP | 24.3 MP | 36.3 MP | 16.2 MP |

| Image Resolution | 4,288×2,848 | 4,928×3,264 | 6,000×4,000 | 6,016×4,016 | 7,360×4,912 | 4,928×3,280 |

| Sensor Size | 23.6×15.8mm | 23.6×15.6mm | 23.5×15.6mm | 35.9×24.0mm | 35.9×24.0mm | 36.0×23.9mm |

| Diffraction Limit | f/17.6 | f/15.3 | f/12.5 | f/19.0 | f/15.6 | f/23.4 |

The above numbers were derived from the following math: ( 1600 lp/mm Rayleigh limit / ( Horizontal Image Resolution / Horizontal Sensor Size in mm / 2 lp/mm) ). See this and this.

Note that the Nikon D800 is diffraction limited at f/15.6, which is very close to the f/15.3 that the Nikon D7000 is limited to. Thus, at pixel level, both the Nikon D7000 and the D800 would be similar. However, note that I specifically used the words “pixel level” – the diffraction limits would not apply the same way once the images are “normalized” or re-sized to the same resolution. If you took the 36.3 MP Nikon D800 image and normalized it to 16.2 (to match the resolution of the D7000), the Nikon D800 would have a serious advantage over the D7000 in terms of diffraction, landing to about f/23.4, which is about the same as what the Nikon D4 can do!

Now let’s take a look at how two sensors with similar resolution would compare. In the above case, it is the Nikon D600/D610 vs the Nikon D7100. As you can see, the full-frame sensor in this case has a little over a full stop advantage in terms of diffraction limit. This basically gives us a good summary – FX sensors have a full stop advantage over DX sensors when it comes to diffraction.

4) Depth of Field Impact

Another issue that seems to be the topic of misunderstanding is how the sensor size impacts depth of field. There is a general consensus among photography experts that DX sensors increase depth of field (with certain conditions discussed below), but a lot of people do not understand what this actually means. The fact is, depth of field is only increased on DX sensors when the framing or the “field of view” between DX and FX is exactly the same. For example, if you are shooting a bird with two Nikon 500mm lenses from the same distance at f/4, one mounted on the D7000 (DX) and the other on the D800 (FX), depth of field on DX will only be larger when framing is exactly the same. Obviously, to get both cameras to frame the bird identically, you would have to physically move away from the bird with the D7000. Since the camera to subject distance is changed, while all other variables are staying the same, depth of field is also increased on the D7000. Now here is another fun example to add to this: since the DX mode on the D800 yields the same field of view as the D7000, you could simply set the D800 to DX mode and you would end up with very similar framing and exactly the same depth of field on both cameras. If you are confused about this, read this excellent article on the subject, which explains all this in detail.

5) The Myth of Lighter Lenses

One thing I have heard a lot from the DX crowd, is that DX lenses are lighter and cheaper. While that statement certainly holds true for wide and standard lenses, it is absolutely not true for telephoto and super telephoto lenses. DX shooters have no super telephoto DX lenses to choose from – Nikon completely ignored that segment. The longest focal length DX lenses are the Nikon 18-300mm and Nikon 55-300mm, both of which are a joke for serious sports and wildlife photography. This leaves DX users with the same heavy pro lenses used on FX. Now some will say that a DX camera allows one to use a budget option such as Nikon 300mm f/4 + 1.4x TC to get to 600mm focal length and the only way to get to 600mm on a full-frame body is to use much more expensive choices such as 300mm f/2.8 + TC-20E III. First, this is only true for low resolution FX bodies, as discussed above (the D800, for instance, would yield a similar result in DX mode as the D7000). Second, this again becomes the question of magnification versus crop and ISO performance. Lastly, you cannot just compare 300mm f/4 to 300mm f/2.8 – both lenses are built differently and provide different options.

6) Crop Advantage

Sure, DX sensor crops out the worst part of the lens, which diminishes vignetting and other optical problems, but who cares about that on super telephoto lenses? Take a look at MTF data for most super telephoto lenses – they all look excellent in the corners. In addition, I do not know of any wildlife / sports photographer that cares about corner performance. Most sports / wildlife shots have the subject in the center or slightly off-center. Nobody will take a shot of a bird in the extreme corners of the frame. So the crop part of the sensor is pretty much irrelevant – DX has no advantage here whatsoever.

7) Viewfinder Size

FX cameras have much bigger viewfinders than DX. This makes it a whole lot easier to see if the bird you are photographing is indeed in perfect focus. With DX, you have to rely on AF a lot, because you just can’t see that well through the viewfinder. If you have not seen how huge the difference is, put a DX and an FX camera side by side and check it out. You will be amazed to see how much brighter and larger an FX viewfinder is in comparison.

8) MultiCAM 3500DX vs 3500FX

In my experience, the MultiCAM 3500FX works better in terms of AF accuracy than MultiCAM 3500DX. While a lot of people argue that both AF systems are the same, having shot with both for a long time (I used to own a Nikon D300) I disagree. In my experience, MultiCAM 3500FX is better than MultiCAM 3500DX. I think it has to do with the fact that FX cameras have a much larger mirror and hence the AF system might receive more light from the lens. Try shooting birds in low light with both the D300 and the D700 (or with the D7100 and D800), and you will quickly realize which camera will end up with better AF accuracy. Hence, my conclusion is that AF on FX bodies is slightly better than on DX. There might also be physical size differences between 3500FX and 3500DX – if the AF modules for both DX and FX were exactly the same, Nikon would not have named them differently. I noticed the same thing with the D600 and the D7000. The former has the same AF module as the D7000, albeit modified for FX. I did some birding with the D600 and the D7000 and I came back with more keepers on the D600 than I did with the D7000. Perhaps I am biased towards FX, but that’s my “real world” experience.

Those who try out FX for wildlife almost never come back to DX. Some people shoot with both, but if you ask those that do, they will tell you that they prefer their D3 to their D300/D300s. FX makes a difference, whether it has to do with image quality, AF accuracy or other reasons.

9) The Original Intent of DX

DX was never designed as a “feature” for getting closer to action, as I have numerously pointed out in my articles. If digital sensors did not cost so much money in the past, manufacturers would not have made DSLRs with small sensors. APS-C was designed for cost reasons alone, to make DX cameras cheaper, not to make DX cameras lighter or better for reach. Most of the advantages of DX cameras are simple marketing tricks.

10) DX Cost Advantage

The only real advantage of DX over FX today, is cost. But with such offers as the D600 and the price of FX sensors continuously coming down, that huge cost difference is not there anymore. If in the past you had to spend 2-3x+ to move up to FX, today that difference is much smaller. Manufacturers are now making feature differences between cameras and intentionally removing functionality from FX cameras like D600, so that their high-end DX lines are not threatened. Can you imagine what a D600 with a MultiCAM 3500FX + 1/8000 shutter + big buffer would do to D7100/D300s sales? With recent promotions, the D600 dropped to as low as $1800 and the price is going to continue to drop. That’s why I believe that DX has no future. Nikon might try to push a D400 later this year, but it probably will be the last high-end DX camera we see from Nikon. As soon as the D600 gets a 51 point AF and a bigger buffer, it will be the end of the high-end DX.

11) Summary

In summary, FX is better than DX for shooting wildlife and sports for the above reasons. The only reason why anyone should be shooting with DX is lower cost. If you can afford high-end FX, there is very little reason to stick with DX. Don’t listen to photographers that say that their D300s or D7100 is better than the D4, because it gives them better “reach”. If the D4 cost the same as the D7100, you know which one everyone would be buying.

At the end of the day, however, keep something else in mind – any camera, whether DX or FX is capable of producing excellent results. It is not the gear, it is the guy behind the camera :)

On the face of it, this seems like a very useful article – except for the fact that it is 10 years old! A lot has changed in the world of photography since then, and a lot has changed at Nikon since then. Maybe much of this is still current (I assume that the basics have not changed), but maybe some of it is not (given the advantages/disadvantages of Nikon’s current FX line-up vs. its current DX line – as a result of all of the changes/improvements in sensors, etc.). These days what up-and-coming photographer is going to rely on a 10-year old article? Nikon’s camera line-up is completely different, its technology is far more advanced, and its overall strategy is different than it was 10 years ago. This article needs to be refreshed and updated as needed.

About FX / DX and reach.

Nikon D500, Nikon 300mm PF and Nikon TC-17-E-II make a great combo.

Birding and tele-macro as well.

This article stands in contrast to other articles I’ve read. In low light I agree that fx bodies outperform dx when the pixel density is matched, but most people don’t have near-limitless budgets (nor are making money from photos) and would like to know the best bang for their buck. Comparing these different characteristics while maintaining a price point would be better for most readers. This article makes more sense to those considering the huge price jumps of going from enthusiast to professional as they went from dx to fx without losing detail.

Dear Nasim,

This is an excellent article. I really enjoyed your debunking of the ‘ great DX myth’! I wonder if you’d consider updating it with the latest Nikon line up battle : D500 vs D850?

Thank you.

i was about to ask this very question before pulling the stop on a D500 which every reviewer claims is the D5 in a DX body

I don’t this debunked any ‘myths’. Cost is a very important factor. My D7500 and 300/f4 + 1.4TC cost around £2,000 (used). Now check out PL’s own review of the 300/f4 against the 300/f2.8. The f4 stands up very well indeed. My D7500 is putting 21mp at 630mm and f5.6. A D750 with a 300/f2.8 + 2.0TC is putting 24mp at 600mm and f5.6. But it’s 300% dearer! And if anything the D7500 has the better autofocus. And it’s much, much lighter – quite a factor for an old codger like me.

Love the PL site, but got to say I mildly disagree with the conclusions in this article.

A lot of visits to this page must be DX shooters wondering if they should switch to FX to improve their action/wildlife shots, and for the vast majority the answer is no – work on technique, or spend the money on better glass.

Nasim’s technical points are correct: If you use the “effective focal length” factor of DX as a reason to buy smaller lenses, then your image quality and your ability to control depth of field for subject isolation will be reduced compared to full frame. Crop sensors are *not* a focal length free ride.

However… There are two cases that are common in my wildlife photography where DX is as good or better than FX:

1. Cropped shots.

A lot of the time wildlife photographers are using the longest and fastest lens that they can carry and afford, and then cropping the result to DX size or smaller.

In these circumstances DX cameras have image quality that is 100% as good as FX cameras, as well as being cheaper and lighter, and probably giving more resolution.

2. Macro.

DX sensors can have an advantage in macro shooting, allowing slightly greater depth of field at the diffraction limit.

Technical arguments around macro get horrendously complicated, but generally if the limiting quality factor is DoF at the diffraction limit(and it often is) then smaller sensors are better, in most other respects bigger sensors are better.

Note that the diffraction limit “f-stop” for DX sensors is lower (larger aperture) than FX sensors, so you could be forgiven for thinking DX=less depth of field, but for macro shooting this is more than offset by the lower magnification required to achieve the same field of view.

For example an FX camera with a 105mm macro lens stopped to f22 will have less depth of field than a DX camera with a 70mm lens at f16, or a DX camera with the 105mm lens at f16 but used at 1.5x the subject distance of the FX.

I personally use both FX and DX for wildlife and DX is used for the clear majority of my pictures, because I mostly shoot small birds and macro.

YMMV.

All that said, there is no doubt that when not cropped or DoF limited, FX will give somewhat better image quality than DX, particularly in low light.

George

Old article, I know, but not sure I agree with the conclusion that FX is better for wildlife. I drank the FX “Kool-aid” and started using that kind of camera for wildlife. Well, I’m back to using DX. Here’s the thing—FX is better if you can fill the frame. If not, and you have to crop that FX image down to DX size, or smaller, you lose the FX advantage. In fact, depending on the camera model, you end up with a worse image. Nowadays, we have the D850 on FX, and the D500 on DX. A D850 image (in DX crop mode) will still only be 19.4 MP vs almost 21 MP from the D500, and on top of that, the D850 is noisier at the pixel level. So by shooting FX and cropping, you end up with a noisier, lower resolution image.

Let’s take it a step further and look at the D7200 (an old camera now). I can use my 200-500 lens and get a 750mm equivalent, 24 MP image, or I can shoot with my D850, crop to the same 750mm FOV, and end up with a 19.4 MP image. At this point, the amount of grain in the image is basically the same.

A DX camera like the D500 or D7200 is actually going to be less noisy, and provide more dynamic range than a DX crop from the D850 (arguably Nikon’s best FX camera at the moment).

photonstophotos.net/Chart…20D850(DX)

I think the gist of it is, FX is better for wildlife IF you can fill the frame. I’d say, I’m cropping my DX shots over 90% of the time, so for me, DX is the clear winner. If there were a 800mm FX lens as cheap and light as my 200-500, then sure, I’d always shoot FX, but until then….

“At the end of the day, however, keep something else in mind – any camera, whether DX or FX is capable of producing excellent results. It is not the gear, it is the guy behind the camera :)”

Or a gal :)

I wonder how relevant this article is today? I just acquired a nikon 300 af s and a TC II 1.4.

I was planning to get a new d7500 for it (d500 is a stretch budgetwise).

However a friend of mine has a, very little used, D800 he wants to sell. It was always overkill for him. If i buy it, i’d get it at a very good price.

I’m not one that always goes for the latest tech. Although ofcourse it can help, but a good camera is a good camera..

I want to do nature with it, birds and maybe eventually use a tc 1.7 as well.

I highly appreciate high iso possibility. Dusk & dawn is nature at its best… Though call.

“As soon as the D600 gets a 51 point AF and a bigger buffer, it will be the end of the high-end DX.”….uh oh, we have a D750, and the D500 is turning out to be a legendary DX body

Hi,

I’m still a bit confused about this topic. I have Nikon D610 camera.

What lens should I buy and what is the main difference between the following lenses:

– Nikkor AF-S 18-300mm F3.5-5.6 G DX ED VR

– Nikkor AF-S 28-300mm F3.5-5.6 IF-ED VR

So I suppose the best option is the 28-300mm because it’s a Full Frame lens. But with the 18-300mm in DX mode you get more zoom. Correct?

You do not get an advantage by in-camera cropping. It is exactly the same as if you cropped with software later. You just throw away some of the image. I have a first generation 18-300. It is not very sharp at all. I wouldn’t consider it. I don’t know if the 2nd generation is enough better to be usable.

What is true is you get more image if you put a 300 mm lens on a 24 mpixel D7200 over a 24 Mpixel D610. The image size cast on the sensor by the lens will be the same size (if it is smaller than the dimensions of the smaller sensor) and the D7200 crams more pixels into that area.

Putting a 300mm lens on the D610 and setting it into crop mode will not give you any advantage. You’ll only have a 16 effective Mpixels sensor (a bit less actually).