There is much confusion out there about the acronyms DPI and PPI. This confusion is understandable, given that people often use the terms in error interchangeably. So what do DPI and PPI mean, and how do they apply to printed photographs and digital image files? In this article, we will answer these questions and clear up any misconceptions you may have about the abbreviations.

Let’s start with some definitions.

Table of Contents

What is DPI?

DPI stands for dots per inch and refers to the resolution of a printer. It describes the density of ink dots placed on a sheet of paper (or another photographic medium) by a printer to create a physical print. DPI has nothing to do with anything displayed digitally! And this is where a lot of the confusion occurs. More on DPI in a bit.

What is PPI?

PPI stands for pixels per inch. PPI describes the resolution of a digital image, not a print. PPI is used to resize images in preparation for printing. To understand this, we also need to understand what a pixel is.

A pixel, or picture element, is the smallest building block used to create an image on a screen. Pixels are square and arranged on a grid. Each square is a different colour or hue. Because pixels are so small, our eyes can not detect the elements on the grid as individual squares. Instead, our brain blends each pixel into a smooth digital picture. Now before those of you with more advanced knowledge call me out and say this is not entirely true, you are correct. Pixels themselves are made up of red, green and blue sub-pixels. These sub-pixels are blended to give each pixel its hue. However, a full explanation of sub-pixels is far more detail than we need to get into for this discussion.

In this image of a hooded warbler, I have zoomed into the small portion of the bug in the warbler’s mouth to 1,600% using Photoshop. At this magnification, you can see the individual pixel elements that make up the image. This enlargement is pixel peeping on steroids! Just a reminder to click on the image below so you can see the details.

Digital Image Size

It is also essential that we understand what digital image size means before we get too deep into our discussion of DPI vs. PPI. The size of a digital photo is created in your camera. It depends on the model of camera you are using and how you have set up your camera. For example, my Fujifilm X-T2 captures a raw file that is 6,000 pixels wide by 4,000 pixels high. If I have my camera set to shoot JPEG, I have three different image size choices: large (L) is 6,000 × 4,000 pixels, medium (M) is 4,240 × 2,832 pixels, and small (S) is 3,008 × 2,000 pixels.

As an aside, if you do the math, 6,000 × 4,000 = 24,000,000 pixels, or 24 MP (million pixels or megapixels). When you hear someone say that they have a 24 MP camera, this is what they are referring to. Again, for all you sticklers out there, I know that my camera has a 24.3 MP sensor, but I’m not going to talk about actual and effective pixels in this article!

For more information about camera resolution, check out Nasim’s article, “Camera Resolution Explained.”

PPI and Screen Resolution

Now down to the nitty-gritty. PPI is also used to describe screen resolution (not to be confused with digital image resolution). The resolution for any particular screen is a fixed quantity. Screen resolutions vary between devices and are continually getting better. The pixel count of my 15″ MacBook Pro Retina screen is 2,880 × 1,800 pixels, and its resolution is 221 PPI. An iPhone X has a pixel count of 1,125 × 2,436 and a resolution of 463 PPI. Displays with higher resolutions have device pixels that are smaller and more closely packed together. Images on higher resolution screens appear sharper and crisper than those same images displayed on lower resolution devices. However, this is only true to a point. How far away from the device you view the image and how good your eyes are also affect how sharp a digital image looks on a screen.

Since the pixel count is fixed for any device, image resolution will not impact how a photo looks on that device. You can export an image at 72 PPI, 96 PPI, or even 5,000 PPI, but for a given device, you will not see any difference in how the picture looks. It is the picture size – the physical number of pixels along the length and width – that changes how the image looks on a particular display screen, not the image resolution.

Here are two versions of the same photograph. I exported them from Lightroom at two different image resolutions. The first photo of the purple gallinule has a resolution of only 1 PPI. The second one was exported at 5,000 PPI. They both have dimensions of 2,048 x 1,365 pixels (again, click on the image to see them at full resolution). I guarantee you will not see any difference in them at all. If you still don’t believe me, drag the images into Photoshop and use the Image Size dialogue box to check their resolution yourself!

X-T2 + XF100-400mmF4.5-5.6 R LM OIS WR @ 400mm, ISO 400, 1/1600, f/5.6

X-T2 + XF100-400mmF4.5-5.6 R LM OIS WR @ 400mm, ISO 400, 1/1600, f/5.6

PPI and Print Size

This is where most of the confusion exists because PPI and DPI are often used interchangeably to mean the same thing, which is wrong! DPI does not apply to digital images! As I said earlier, DPI is a physical property of a printer, not the digital image.

When talking about print size, PPI refers to the number of image pixels from the digital file that will be used to create one inch on the printed medium. The math is quite simple to determine the size of the print that can be made from a digital file. Take the pixel dimensions of your image and divide those values by the resolution (PPI value). For example, if I print one of the 6,000 × 4,000 pixel image files from my X-T2 at 200 PPI, the photograph would be 6,000/200 = 30″ long and 4,000/200 = 20″ high.

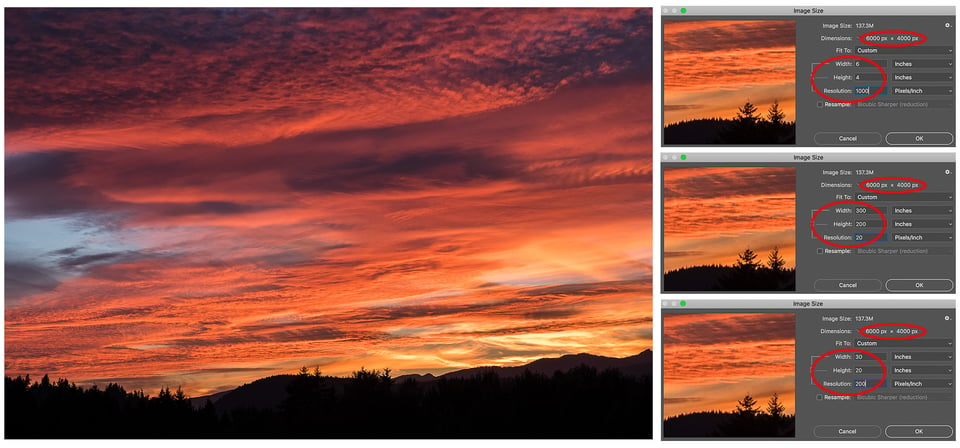

Pixels do not exist on paper. But to simplify the explanation of PPI and print size, I want you to imagine that each image pixel from the digital file is to be represented by a small square on the photo paper. Let’s call each of these printed squares a “paper pixel.” Each “paper pixel” will have the same colour tone as its corresponding pixel in the digital file. Now let’s take a look at the Image Size dialogue box in Photoshop. You will find it under the Image Menu. First, make sure the Resample Box is unchecked. Notice what happens when we change the resolution. The pixel dimensions of the image are not altered (they remain 6,000 × 4,000). You might also notice that the size of the file remains constant, too (137.3 Megabits). However, the width and height of the image change based on the calculation above. These screen clips illustrate this. At 1000 PPI the printed picture is only 6″ × 4″. At 20 PPI, the print is 300″ × 200″! And at 200 PPI, the image will be printed 30″ × 20″. What this means is simply that those “paper pixels” are much bigger for larger prints than for smaller ones. If you look at the 300″ long print and the 30″ long print from a foot away, you will not notice the individual “paper pixels” in the smaller photograph, but you will see each square on the large print.

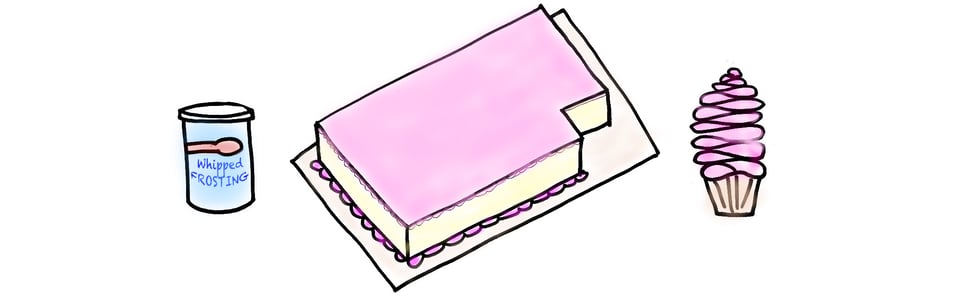

Here is an analogy for you. Imagine the total number of pixels in your digital image as a can of icing. There is a fixed quantity of frosting in the container, and you don’t have the ingredients to make more! You could either thinly ice a large rectangular cake with the available icing. Or, you could pile all the frosting thickly on a small, single cupcake. The bigger you make the cake, the less densely it is iced (smaller PPI value = big, low-resolution print). Or conversely, the cupcake has a very dense layer of icing (large PPI value = small, high-resolution print). Apologies for the sketch – there is a reason I use a camera and not a paintbrush!

How Big a Print Can I Make?

One of the most common questions I get asked is “How big can I print this image?” I am going to give you a short and long version of the answer!

The short answer goes like this. Many print labs suggest that you deliver your digital files at a resolution of 300 PPI (although some will mistakenly ask for a resolution of 300 DPI). So, divide your digital image dimensions by 300 to determine the biggest print possible from your file. Continuing the X-T2 example, those files can be printed 6,000/300 = 20″ long by 4,000/300 = 13.33″ high.

So now the long answer to “How big can I print this image?” It depends! There is nothing wrong with printing a large print at a lower resolution. You can print at a lower resolution because you do not look at large prints from up close. The 300″x 200″ image we discussed above is billboard size, and the “paper pixels” are approximately 1.3 mm wide. When was the last time you looked at a billboard from a foot away? That is the printed equivalent of pixel peeping! If you view this image from across the street, you will not notice the jagged composition of the larger individual “print pixels.” The image edges will look sharp, and the color tones will have smooth transitions. Even large prints (16″ × 20″, 24″ × 36″) that you hang on the wall are viewed from several feet away (at least they should be), so using a resolution of 200 or 240 PPI is often perfectly acceptable and will produce high-quality prints.

The print medium also plays a role. If you are printing a photograph with lots of fine detail on a glossy surface, you may want to use a higher resolution. A higher resolution will ensure that all the fine detail is rendered crisp and sharp. On the other hand, printing an image on canvas does not require as high a resolution because detail gets lost in the texture of the canvas.

Regardless of which output resolution you use, to ensure that you can print as large as possible, make sure your camera set to the largest file size available. Remember I said above that if I have my camera set to JPEG, I have the choice of three image sizes. If I accidentally set my camera to small (S), then the biggest photo I could print would be 10″ by 6.67″ at 300 PPI.

Resampling

What if you don’t have enough pixels in your image to make a large print? If your image’s pixel dimensions are too small, you can resample the image. Resampling adds pixels to an image file. However, I would not recommend you do this! Resampling degrades image quality, sometimes drastically! If you need to make the pixel count of your file larger, use specialized software, such as On1 Resize. When pixels are added to your file, the resampling software “guesses” what the pixels it is adding should look like based on existing neighboring pixels. In simple terms, the original pixels are spread apart and new pixels are placed in between them to fill the gaps.

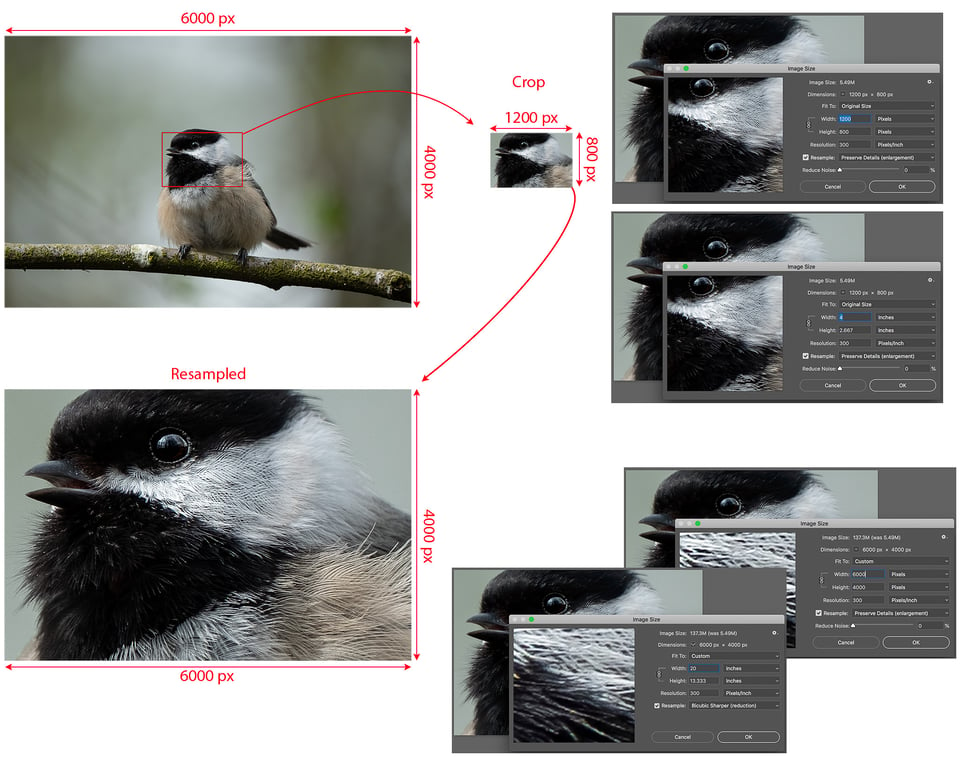

Take a look at the graphic below. The first photo (top left) is my original 6,000×4,000-pixel file. At 300 PPI it can be printed 20″ wide. The second image is a 1,200×800 crop of the chickadee’s eye and also has a resolution of 300 PPI. The image quality on both of these is excellent. However, I could not print the crop any bigger than 4″ wide given its small dimensions. If I want a 20″ print, I have to upsize the image by resampling.

Notice what happens to the crop’s pixel dimensions when I check the Resample box and type in 6,000 for my new width (bottom image). The physical size of the file, both its dimensions and amount of memory required to store it have increased. However, notice how soft the details are in the feathers and around the eye. Photoshop is doing its best to add the appropriate pixels to make the new larger image file. These new pixels didn’t exist in the original. Although I can print this new file 20″ wide, the print would not be nearly as sharp as the original.

You can also decrease the pixel dimensions of a digital file by resampling. Downsizing is done to minimize the file size for web images and for emailing pictures to friends. In fact, if you haven’t clicked on any of the images in this article, you are actually seeing a downsized file which is 960 pixels wide. The software behind the website downsizes the images so that the article will load faster. Downsizing can also degrade an image, since you are getting rid of pixels from the original file. That is why the images embedded in the article do not appear as crisp and sharp as the higher resolution file you see if you click on the image. In fact, my original 6,000 × 4,000 pixel images are all downsized to files 2,048 pixels wide before I upload them to the website. This is a compromise between image quality and file size. And it allows viewers on different screens to see the entire picture without having to scroll. These files take up much less room on the server than the original image files would!

DPI Explained

Last but not least, DPI refers to dots per inch. But these dots are little tiny dots of ink, not square picture elements. Printers create a print by spraying miniature droplets of ink on the paper. It takes many dots to form one pixel of the image.

I’m not going to get into any details about printing. Topics such as how the dots are made, the patterns they are arranged in on the paper, or how different colours and shades are created are things that are not important to the average person who wants a physical print of their photograph. The layout of the ink droplets is all taken care of by the internal software on your printer.

It is enough to say that most printers have several print settings that control the density of the ink they apply to the paper. However, for most home printers, you do not set the value of the printer’s resolution. Instead, you select it from settings like draft, normal, best or photo. Each setting puts progressively more ink on the page because more small dots of ink are sprayed closer together. Inkjet printers often have resolutions between 300 and 720 DPI. Some laser printers and photo printers have resolutions exceeding 2,400 DPI. I want to stress that DPI is a function of the printer. It is not a setting that you choose in your photo editing software. The image size in combination with the DPI of the printer determines how many dots of ink are used to represent a single digital pixel on the paper.

Summary

A pixel is the smallest building block in a digital image. Pixels are square and laid out on a rectangular grid.

Pixel count, or image dimension, is the numbers of pixels across the length and width of a digital image.

PPI is a term that describes the resolution of a digital image and determines its size when printed. To adjust the print dimensions for a digital image, modify its PPI (without resampling). Doing this does not affect the pixel count of the image. And remember, the PPI of an image does not influence how it will display on a device screen.

DPI is a function of a printer. It describes how tightly little dots of ink sprayed on the paper are placed to create a photograph. DPI is not used (at least it shouldn’t be used) to describe any aspect of a digital file.

Hopefully, this helps to clear up some of the confusion between DPI and PPI. The next time someone asks you to send them a 300 DPI file for printing, feel free to correct them! Or if someone tells you that 96 PPI is best for posting images on Facebook, you can inform them that PPI has nothing to do with photos viewed on a screen!

If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below, and thanks for reading.

it was a wonderful article I have read it from the beginning to end , before reading this article I have many doubts about dpi and ppl , how big size I can print and after reading this article my doubts became much more because I couldn’t understand the math in it at all even now am not able to understand dpi and ppl but this was a wonderful article ….

Really great info!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on something I’ve noticed that my windows file explorer. It uses “dpi” rather than “ppi” – since it is a digital image, am I ok to assume that it really is referring to “ppi”? My overall assumption is that Microsoft is using “dpi” as a false equivalent because the consumer is more accustomed to that. This is on images that have been exported in software with “ppi” metadata.

his is so detailed that I had easy time understanding.

Great article it helped a lot!

One thing I don’t understand is, when I did what you suggested which is downloading the gallinule images and see them in Photoshop, they have the same ppi. Why is that?

Thanks! Keep writing!

Great article….Thanks! I have been wracking my brain trying get this PPI, image sizing thing figured out. Although I will still have to work it out more in my head, your article has solidified what I have read from the other writers of PL, but somehow easier to comprehend. Maybe the cupcake analogy…I don’t know! Takeaways;

if exporting to a media source, facebook or whatever, PPI in inconsequential. If exporting for print, in my case I will set PPI to 300 as I have a 24MP camera and shoot RAW…defaults to largest size available.

PS born and raised in Vancouver, now in the Okanagan…

Thank you, Tim. And great to “meet” a fellow Vancouverite!

So what is the difference between raster and vector images, and how does that affect how much I can enlarge an image? JPEG, EPS, TIFF, PNG, SVP? (I don’t even know what the acronyms stand for; I believe that JPEG and PNG are raster, EPS and SVP vector, not sure about TIFF—vector?)

Help!

beautifully explained. I was just confused by ppi and dpi, in spite of having a science background. Congratulations

The worst article I’ve read yet on PhotographyLife.

You’ve taken a simple subject and spent several long-winded pages making it look difficult – I can’t help but wonder if you actually understand it yourself.

Contact me if you want to know how to write this up properly – because, frankly, this sucks.

Hello Elizabeth,

Fantastic article indeed, explaining a lot of things. Thank you for that.

I have just one more “practical” question:

How should we understand the _relationship_ between the PPI that we set for the image file, and the DPI property of the printer?

What are the implications?

Let’s assume I have a printer that is capable of printing at 600 DPI. -> Which PPI should I set (for best results) when exporting my images for printing?

Should I set the PPI ideally at the same value as my printer can print DPI (ie. set PPI=600)? — (I.e. as far as I understood your article, each image pixel would be then printed out as one “printer dot”, right?)

Or should I (for better printing results) set the PPI _lower_ than the DPI of the printer? For example PPI being 1/2 of my printer’s DPI: like set the PPI to 300, which – in my understanding – would have the effect that each image pixel would be printed (“constructed”) by four “printer dots” ? [two in upper row, and two in lower row — I guess all 4 in the same ink color??] — I mean in this case the printer can do _more_ dots per inch than the image file delivers as pixels per inch, right?

Or should I even (for better print results) set the PPI higher than the DPI of the printer? For example set the PPI as a double of the printer’s DPI (1200?). — Lets say I have a high-end camera capturing images at tons of megapixels, (so I could squeeze really lots of pixels into 1 inch, and still have a sufficient paper print dimensions)

and I really do set the PPI to a high value during the export (like 1200)… what happens in the printer then??: Will it use 4 neighbour pixel color values to average 1 “printing dot” color ?? Will it give a better, or a worse print result at the end ?

Would be great if you could answer the above questions!

–Martin

PS. I think I understand, that for a given fixed printer’s DPI – when I change the PPI in image export, then it will immediately impact the actual dimensions of the printed image on paper (in inches). But let’s put this aside for a moment.

(I might resample the image to a different pixel size in computer before printing, to achieve a _particular_ dimensions on paper)

I only want to understand which PPI is better for a given printer DPI? Equal,smaller,or higher?

Hi Martin, thanks for your question. The DPI on your printer is completely separate from the PPI you set on export from LR or Photoshop (or whatever post-processing software you are using). The DPI on your printer is usually much higher and represents how many micoscopic dots of ink are sprayed onto the printing medium to create the image. PPI is used to tell the printer how large to make the image. For example, if you have an image that is 6000×4000 pixels and you export it at 200 PPI, then it will be printed 30″ x 20″, regardless of the DPI on your printer. Check out Betty’s response 22.2, she gives a good explanation of printer DPI and how it affects image quality. I hope that helps!

An outstanding article, the best I have read on the subject(s)

Thanks so much, Ian! I appreciate your feedback

I second that !