If there’s one aspect of a lens that is more discussed than any other, it’s sharpness. In wildlife photography, sharp photos are especially sought-after, with just a few exceptions. Fine feather detail in bird photography is one of the first things I look for in my own shots, personally. But how much does a lens’s sharpness really matter in wildlife photography?

Table of Contents

What is Lens Sharpness?

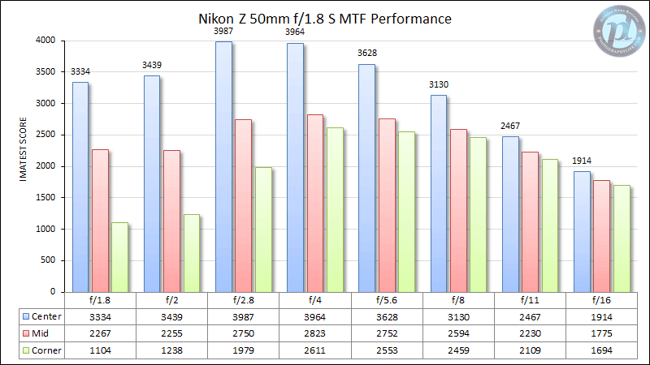

In short, a lens’s sharpness is its ability to resolve detail on the subject. But lens sharpness isn’t just a single metric – the same lens that’s sharp in some cases may be below average in others. For example, let’s take a look at our sharpness measurement from Imatest for the Nikon Z 50mm f/1.8 S lens:

This is actually one of the sharpest lenses we’ve ever tested in the lab, but even so, you can see that the sharpness depends on the aperture and the portion of the frame that you’re considering. The Nikon 50mm f/1.8 S behaves like most lenses: It is most sharp in the center, and it has a “sweet spot” of the sharpest aperture values (in this case, around f/2.8 to f/5.6).

The sharpness or resolving power of a lens is dependent on the optical formula of the lens. More modern and complex designs often – but not always – result in better sharpness and fewer aberrations.

In general, expensive and exotic telephoto lenses (like 300mm f/2.8 lenses, 600mm f/4 lenses, etc.) tend to be among the sharpest optics of any lens today. But there are plenty of cheaper telephoto lenses on the market, too – some of which are not as strong optically. Does that matter? Well…

A Sharp Lens Does Not Mean Sharp Photos!

When people use the term “sharp photo,” they are actually referring to the presence of detail. This detail depends upon much more than just the sharpness of the lens.

In other words, don’t expect to pick up the latest 600mm f/4 and automatically get beautiful, razor-sharp wildlife photos. There are many other factors to consider first.

One of the biggest ones is subject distance. If the subject is closer, detail such as bird feathers will be larger relative to the frame, and thus you’ll capture more detail on them. Plus, being closer reduces the distortion effects from atmospherics.

There’s also the focal length of the lens. If your subject is far away, the world’s best 400mm lens will not compare to an average 800mm lens in the detail you’re resolving, since the 800mm lens magnifies the subject so much more.

This is one reason why it is so dangerous to judge lens sharpness purely on sample photos, especially if you’re not seeing the original Raw files. For example, a nearby bird photographed with a cheap 70-300mm zoom will appear sharper than a bird far in the distance photographed with a high-end 300mm f/2.8.

There are other factors, too, including:

- Shutter speed and subject movement: Pick too slow of a shutter speed, and you’ll get motion blur – a huge culprit behind sharpness loss!

- Missed focus: Front-focus or back-focus can make a $10,000 lens look worse than a point-and-shoot camera lens.

- Sharpening in post-processing: This won’t magically create lost detail, but it can make existing detail more apparent.

- Image noise: Shooting in low light and high ISOs is a recipe for losing details. Proper noise removal can help, but overdoing noise reduction can make the problem worse.

In other words, the final level of detail present in your photo depends on a lot more than the pure resolving power of your lens.

A Below-Average Lens Does Not Mean Blurry Photos!

It’s obviously true that sharp lenses can resolve more detail (at least if you do everything else right). This helps for things like cropping your photos or printing a bit bigger.

But, if you’re filling the frame with your subject and you have plenty of light, you’ll capture surprisingly similar levels of detail with a budget telephoto compared to a super-sharp exotic lens, so long as your print size is reasonable. I’ll put it like this – if you’re getting blurry photos with any modern lens, it is unlikely that the lens’s resolving power is to blame.

Recently at Jardim Botânico São Paulo in Brazil, I managed to get very close to a Southern Lapwing with my Nikon 70-300mm AF-P DX lens. This is a $400 entry-level telephoto zoom, and although it’s perfectly acceptable, it’s not going to be in the same conversation as Nikon’s exotic primes. Yet because I had proper focus, a fast enough shutter speed, a low enough ISO, and a subject filling the frame, the photo is very sharp up close. The limiting factor for making a large print is my pixel count, not the lens at all!

Granted, these were close to ideal conditions. For more difficult subjects or extensive cropping, the 70-300mm would have shown its weaknesses more clearly. But it goes to show that a basic – or even a below-average – telephoto lens is not a fatal blow to sharp wildlife photos. It’s better to fill the frame with a cheap lens than to crop extensively with something expensive.

Should You Upgrade to a Sharper Lens?

Whether you should upgrade is a tricky question. When you get a more expensive or higher-performing lens, sharpness is far from the only thing that will improve. For example, going from the Sony FE 200-600mm f/5.6-6.3 G to the Sony 600 f/4 GM does not just give you more sharpness, but faster autofocus and an f/4 maximum aperture. Frankly, these improvements matter more to the photo’s overall sharpness, compared to the difference in resolving power between the two lenses.

In my own wildlife journey, I used to shoot with the Tamron 150-600mm G2 lens and later upgraded to the Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF lens. In this case, the faster autofocus and lighter weight of the lens were the most noticeable improvements, and both had direct impacts on the sharpness of my photos. Yes, the 500mm f/5.6 is the better of the two lenses in lab tests, and that shows up sometimes in the field – but it was the other features that made a bigger difference to me.

Not to mention that most of the time, the problems in a wildlife photo run deeper than sharpness (whether lens sharpness or otherwise). It’s much more important to focusing on lighting and composition (gasp!) than pixel-level detail. And even when the problem specifically is insufficient detail, the most likely culprit is that you need to get closer to your subject.

That brings me to another point: the degree of the upgrade. To bring up one common situation, if you’re currently shooting with a shorter lens plus a teleconverter, switching to a lens with a longer native focal length will usually be a nice upgrade in terms of sharpness (especially if it’s a prime lens).

On the other hand, the differences in sharpness narrow once you climb the ladder of high-end lenses. If you’re still not getting adequately sharp photos with some $2000+ telephoto prime lens, you better not be blaming the lens, unless you dropped it off the ladder.

I remember that Libor surprised a lot of people when he noted that the Nikon Z 400mm f/4.5 (a $3250 lens) is basically as sharp as the Nikon Z 400mm f/2.8 TC (a $14,000 lens). There are good reasons why pros will buy the f/2.8 prime – mainly the wider maximum aperture and built-in teleconverter – but sharpness measurements in the lab are probably not among them.

Finally, there is no doubt that lenses are getting better with time. Modern lenses, even the budget ones, are much better than a typical lens of ten years ago. I would have no issue using modern telephoto zooms like the Sony 200-600mm, Nikon 100-400mm, and presumably the upcoming Nikon 200-600mm. The sharpness of those lenses may be worse than a high-end prime in the lab, but in the field, those differences will often disappear.

So, how would I answer the question I posed in the title of this article? I’d say that lens sharpness doesn’t matter too much beyond a certain point, and we’ve mostly reached that point with modern lenses, even cheaper ones. But paradoxically, upgrading to a sharper lens can still be worthwhile for sharpness-obsessed photographers! That’s because the sharpest lenses on the market (usually the exotic primes) have other features that matter more. They have wider maximum apertures, faster focusing speeds, better image stabilization, and so on. Those features can directly lead to sharper photos. So if you switch from a 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6 to a 300mm f/2.8, you’ll definitely get crisper photos, but probably not for the reason you were thinking.

And as a final note, let’s all take a step back if possible. It can be kind of silly how much photographers obsess with sharpness these days – and I’m guilty of it too. I love prints that look razor-sharp up close. But some of the best wildlife photos I’ve seen still have a few issues when your nose is up against the glass. Before you spend a fortune upgrading your lenses, make sure you know what you’re gaining and exactly how it will help your photography.

I think the thing I wonder is these values sound good/poor when compared to each other but what do the values in Imatest actually equate to on their own. For an A3 print, is a value 2500 in the centre good? I’m trying to decide on the 24-120 4 and the 35-150 2/2.8 for a Z8, and the former is sharper and lighter, the latter a few more compromises a touch more reach, less sharpness… but maybe it’s enough at 45mp?

You take of cheap, and high price lens, but there are alot of variable to consider, weather, the person, and distant! I been taking some fairly sharp pictiure of a nest eagle with a nikon- 1000 with a mono pol, the nest is very deep in a restricted area , and l tried with trampon 150-600 len it can,t make, but other wise l ” would” prefer it!

I noticed that you completely ignore any references to any Canon products as being sharp.

Canon has sharp and not sharp lenses just like every other manufacturer.

IMHO, topics such as this have no answer. What is sharpness? You claim It is the ability to “resolve” points. What we don’t see, we don’t know is missing. Edges can look “sharp” when really the lens/camera combo have obliterated subtleties that would otherwise make an image look unsharp. The original App Lanthar lenses from 40 years ago were extremely sharp, but not in ways that would appear so in this discussion. Their subtle contrast provided endless shadow detail without ever looking “crisp”. The feel was more three dimensional. At one point there was a classic Nikon look in black and white. It was really just a high contrast presentation that accentuated edges. Is sharpness an illusion created by the inability of a lens to resolve further at the expense of contrast and colour? If we zoom in to 800% will it still look sharp? It we look at the image as a billboard 60′ x 90′ from half a mile away, or as a 6 x 9 print, will it look sharp?

Recent Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards featured a photo by a 14 year old with a Nikon Z9 and the 400 tc version. See what $21,000 plus travel expenses can do! I love exotic birds and wildlife like anyone, but this exclusive equipment club gets a bit tedious.

Yes, people with money to go to exotic locations have an advantage in competitions. For sure.

I found this article very interesting and the associated comments. Like most people I am obsessed with sharpness. I have 2 nikon p900 cameras which do have a long focal range although in practice I don’t keep many photos taken above 800 mm. I have got a Canon RB but i have not yet got a long lens for it. Compared with the p900 it does seem complicated to use. I think you develop a love hate relationship with a camera because it does produce variable results. My p900 photos are on my blog Birdwalkermonday.blogspot.com

I agree with the author Jason that sharpness need not be the be-all-end-all in wildlife photography. I feel the most important thing in virtually all photos is the emotional impact the photo has on the viewer. With this in mind I would say that getting closer to your wildlife subject to achieve sharper images often leads to the subject becoming wary of the photographer and ceasing its normal behavior as it either freezes or flees. While the frozen subject might make a good ID photo in a guidebook, it says little about the animal’s life, environment or behavior. So rather than filling the frame with a nervous subject, backing off with a longer lens (at the cost of some sharpness due to distance/atmospheric disturbance) can lead to more engaging images as the subject is free from fear of the photographer. And even if you don’t have a longer lens, backing off and showing the animal smaller in the frame and interacting with its environment included can lead to great photos as well.

You need the Z9 or A1 (or Canon option) with the 600 or 800 mm equivalent to start. Then the gimbal, the monopod, the blind, the cammo gear, the nature specialist to guide you to the right spot at the right time. Ideally, another Z9 with a 100 – 400/tc as a backup too, don’t forget the CF Express cards, the extra batteries. Should be simple.

“, if you’re filling the frame with your subject ” “…you need to get closer to your subject.”

This glosses over one benefit of increased sharpness: cropping.

Hey Bo, thanks! I did mention cropping as a benefit of sharpness in the article. Of course, getting closer still beats cropping if you can do it :)

As a wildlife photographer, I can say lens sharpness matters almost not at all in the field. Even if the animal is staying still, the furs are moving, eyes are moving, tail or wings can be moving in the wind etc. You are shooting a moving subject no matter what. Autofocus and shutter speed matters a lot more than lens sharpness to get a good picture.

The more I shoot, the less I care about lens sharpness. I don’t even care about sharpness loss with TC’s anymore, since the loss is mostly in the DX or FX corner, whereas the animal is 90% of the time in the center anyway.

Many years past I upgraded to a 400mm F2.8G Lens and was blown away in how it produced an image, when compared to images from other used lenses. The capability to isolate the subject left the added perception the subject was much improved as a sharp image.

Roll the clock forward and now a Z System only user and using a 400mm Lens, I have revisited images captured of same subjects in similar settings captured on the F Technology and compared these to my Z Technology images.

There is as a result of my skill set and my subjective assessment, very little, if any differences that can be detected in the sharpness of the subject where the focus point is optimised.

The idea of getting closer to the subject and increasing the frame fill has always benefitted me, to capture the sharpest images when all camera settings were correct for the capture.

In the past, as a Winter activity, I have worked with the owned lenses to learn where the focus is optimised for how I want to use the lens. This has enabled me to be confident with the lenses in the field.

I have used wide angle lenses at closest focal length, capturing Damson and Dragon Flies and do not see the need to improve on the image captured. The idea of a lens to produce more capture opportunities is the most desirable change for these subjects.

This suggests familiarising oneself with their lenses and learning where the lens offers a optimised performance has an importance. Using the lenses on subjects that are working with the lenses discovered optimised working parameters for producing a sharp image that impresses, will increase the success rate of captures and the users confidence.

How an individual produces a image in post editing takes time, I attempt to work on the basis less is more. This has been learned in the early days of post editing through working with a duplicated image.

One image edited with an over used tool, where the overall image is affected by the excess of tooling and the other just tweaked with the tool, to accentuate certain areas of the image. After a period revisiting the two images, the over used tool edited image has always been rejected by myself, usually due to how fake the sharpening appears.

So basically, if a camera and lens were able to take good pictures 5 or 10 years ago, they should still be able to today. The advertisers and camera manufacturers want you to feel inadequate and deprived with your OLD, out of date, non current, gear. The beauty about cameras in the days of film was that they all did essentially the same thing and the film was really the greatest limiting factor, not cameras. A Minolta SRT 102 could easily accomplish the same task as a Leica, Nikon or anything else. Further obsolescence and product cycles were so much longer. It was possible to own and use a Hasselblad 500 series camera for decades without feeling the need to “upgrade”. The lifespan of a modern camera is years at best.