When wildlife photographers think of Brazil, they might think of the Amazon or Pantanal. And although these biodiversity hotspots are full of amazing animals, they are not the only places in the country for wildlife photography. They can even be touristy and highly guided at times. If you want to explore a wild environment, where else could you go in Brazil? Well, the state of São Paulo may not be the first to come to mind. But, it offers one of the largest remnants of Atlantic Forest with a plethora of conservation areas virtually unknown to the rest of the world. It is also where this story starts.

On the Periphery

My wife and I are looking out through the windshield, driving by the estuaries of southern Brazil. The city is giving way to forests – remnants at first, but signs of civilization slowly become less prominent. The cool, blue ocean fog comes in waves, surrounding the trees, and softening the harshness of the intermittent concrete. Our destination lies deep in the Atlantic forest, but now we are just on the edge of it. Birds that thrive on both the forest and the cultivated land are starting to appear.

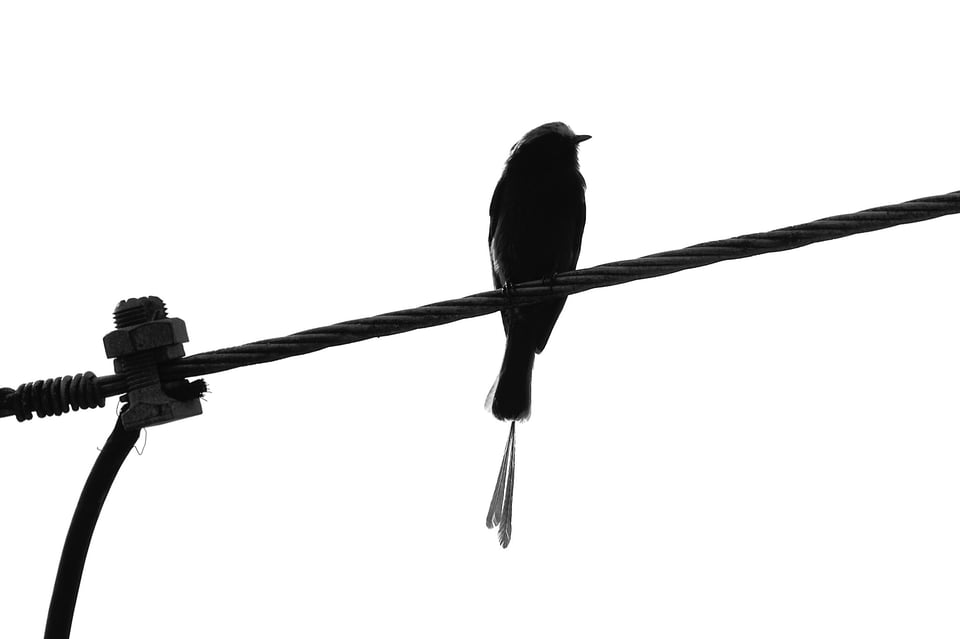

A flycatcher calls attention to itself, leaving its perch but then returning, using its streamer tail to draw wavy patterns against the clouds. It’s the Fork-tailed Flycatcher. They’re chasing Tropical Kingbirds and each other, too. Palms mark the edge of a ravine and provide an oasis for the hyperactive birds.

I’ve seen these flycatchers in cities, but they seem happier here. Less vigilant, more playful. Another flycatcher comes, but it’s not the Fork-tailed. This time, a bright, saturated, red flash of feathers moves from branch to fence and back. I rarely see color that looks so saturated in nature, and this Vermillion Flycatcher is one of those lovely exceptions. Day after day, he will revisit his favorite perches.

But this border between forest and town is only the beginning. Gently swaying in the wind is a gate a few meters away. That gate leads to…where? Off into the forest, off into the land of thick branches that disappear into the darkness. Yes, for wildlife photography, branches can hide the birds and make it tricky to capture good shots. But, obscured birds means birds with a nice home. Happy birds. Birds on their own terms, and not on the terms of a commercialized ecosystem tamed by an ecolodge. Here, I may get less photos, but if I do get one, it’s one that means something to me.

In this wild habitat, a Southern Yellowthroat peers out for a second, only to hide once more, calling, singing. I can hear Spix’s Spinetail and Campo Flickers take refuge in a huge tree. A few Smooth-billed Anis come out, playing on the fenceposts and then hiding, peering out and deciding whether to fly away.

Droplets of rain and fog surround me, and walking through the tall grass is peaceful. Then, I feel a shock as if I had stepped out from a cave into blinding rays of golden sun. A huge pair of wings propels a large, feathered body into the forest. Was it a raptor? My heart beats faster as I move slowly ahead. Where is it? It can’t still be around, right? I look, but I don’t dare hope it hasn’t disappeared. And then…

Unbelievable. It hasn’t left! The majestic bird is looking, scanning, resting – calmly sitting and supremely aware. A Striped Owl, Asio clamator. We’re near the southern border of its range, which extends as far north as Mexico. It’s beautiful, just standing out agains the dark greens. It’s not tense, and it permits a few photos, turning its head here and there like a model. Three minutes later the branch is empty. Finding a bird like this is magical, and it’s one of the best sightings of my life.

The more birds I see, the more I cherish seeing birds in the wild – untamed, unhabituated, and in their world. I remember that months earlier, I did some research on the Pantanal. One ecolodge described how they have habituated birds. I feel that humans are all too eager to modify the environment without limit.

In terms of photography, I wonder if that’s because, by placing the photo as a mere end-product to be perfected as a commodity to be scrolled past, we are slowly forgetting and dismissing the value of the human experience behind a photo. Instead, we should minimize our traces, and notice the life around us, rather than ourselves. To minimize one’s presence is nothing else than an invitation to the soul of the other.

Into the Forest

The next day, we drive to a place called Legado das Águas – legacy of the waters – a large private reserve that holds about one percent of the remnant Atlantic Forest. Down the dirt road, the houses vanish, and there is just forest.

Then, the rushing sound of water breaks the silence of the trees. A river appears, and across it a bridge provides passage. We get out and look. There are no birds, but the patterns of water below hypnotize me. Suddenly, a huge black mass rushes within meters of my face! Spinning, I see it’s the White-collared Swift, and there are three of them. They are looking for insects, I guess. Swifts are amazing birds, and it’s rare to see them perched. They spend so much of their lives on the wing. It must be such a different world for them, most of the time seeing our entire world as a distant pattern from above.

We drive a little farther and arrive to the Reserve’s restaurant. I think to myself that even if I don’t get any good photos of birds, the cheap but delicious lunch buffet will give me energy to try. I quickly eat three plates.

But there’s nothing to worry about. With the arrival of the southern Brazilian spring, the flowers are blooming, the birds are plentiful, and the forest is pouring out rich oxygen. Frequently, I stop and exhale with all my might, then inhale deeply, trying to hold this precious, sweet forest air in my lungs forever. I look up, and in the distance, the flash of a Long-tailed Tyrant is unmistakable.

And any time I see flowers, including those here in Legado das Águas, I think hummingbirds. Yes, here they come! A large one flies by only momentarily, but a smaller one stays. Its gentle spotted throat gives it away as the Festive Coquette. It darts from flower to flower but stays long enough for me to get a picture or two.

Later, a staff member gives me confusing instructions on how to find the cauré. But what is the cauré? I’m not too familiar with the Brazilian names for birds. It’s some famous bird, I guess, but it seems to be impossible to find. They say it’s on a white tree. Well, there are about a million whitish trees around, and all sorts of other ones besides. I hope it’s not a Rock Dove.

“It’s supposed to be at the end of a trail,” someone else says. “Near the end, and very easy to see.” I’ve heard that before, and not in a good way, but let’s try anyway. Well, the forest is getting dense again, and the light is not terribly good. I call it “ISO 20,000 light”. At least there was a Bananaquit at the start of the trail.

I do see some trees that might be the one favored by the mystical cauré. But no bird. However, down below there is a dam surrounded by birds flying in all directions. Swallows. They use holes in a concrete wall to launch themselves out for the hunt. They are deliciously cute and they don’t mind us too much. We stop there, rest, and forget the cauré.

After some time with the swallows, we head back. The rain intensifies, but the swallows fly as carefree as ever. Closer to the path, a tropical Kingbird perches against the foggy, lush mountains in the rain. A shot or two, and it’s time to go back to the trail.

As I slowly moving up the road, something big flies! Something cool! It lands on a very characteristic white tree. It’s so out of the ordinary that it must be the cauré. Now I understand. It’s the Bat Falcon! I take a record shot, not letting myself hope that it will stay as I move into a better position.

But this Bat Falcon is unperturbed, preening and occasionally flying down and away and coming back up once more. Is it hunting? I examine the tree carefully, trying various angles to get the most pleasing arrangement of branches and pose. Luckily this tree only has thick, beautiful branches, all positioned against a distant mountain background, colored blue in the gentle rain.

On the Road

I wish I could spend the rest of my life in this forest, just observing animals. But it’s time to move again, just a hundred kilometers away.

We pass briefly by a place supposedly good for birds, but it turns out just to be a feeder. I don’t oppose feeders categorically, but this is the worst kind of feeder because they feed the birds so much that the birds are fighting, and we leave as quickly as we can. This sort of touristic overexploitation for me has no place in bird photography, and there are two new birds I see that I don’t even add to my list.

Thankfully we leave and come across a forest trail. This one is so dark that it’s almost impossible to see any birds except for one White-throated Spadebill. This isn’t the first time I’ve seen this species. I think they must be curious birds because they always come so close. Are they checking us out, wondering what we are doing? It lingers above and then moves to a branch right over the path. I take a risk and try a long-ish shutter speed. Then it’s gone.

Carlos Botelho Park

We make our way to our destination. The forest habitat changes into farmland punctuated with small cities. On the road, huge trucks carrying eucalypts and other timber are a reminder that the beautiful forests are a rare exception, and not the rule.

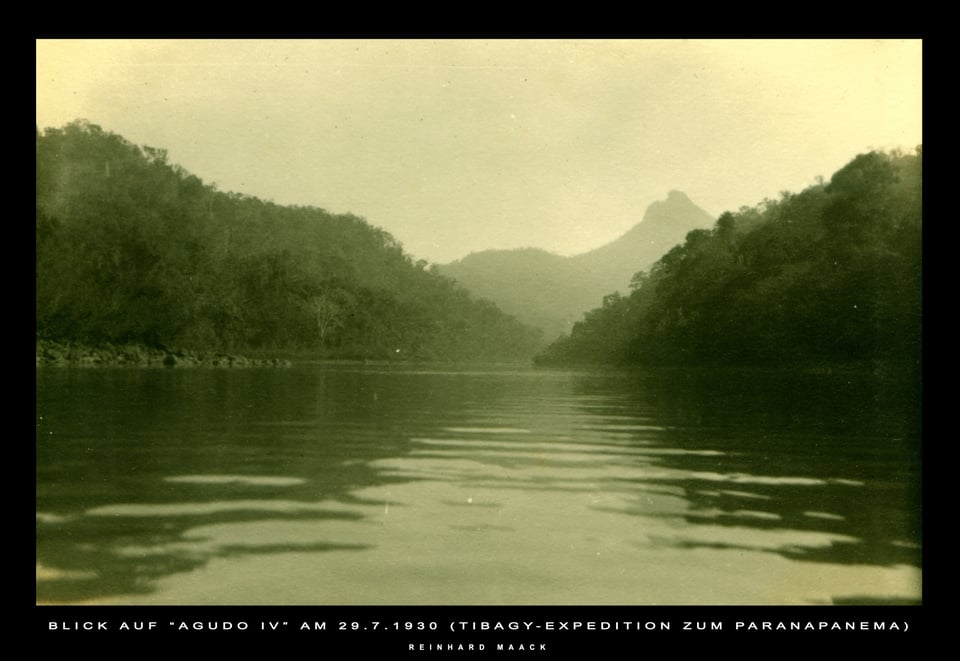

The uniform monoculture farms give way to the scarred wilderness of the Carlos Botelho park. We are staying near the park in an Airbnb run by Adilson Brito and Edi Oliveira, a couple with a passion for conservation. They own 30 hectares of land nearby that once was a soybean plantation, but that they committed to rewilding. Adilson gives me a few rare photos that he scanned from an expedition of Reinhard Maack. Maack was an explorer, and his photos show immense swaths of untouched Atlantic forest that no longer exist today.

But Adilson tells us that the Atlantic forest has an incredible regenerative ability, and the evidence is right before our eyes. They started rewilding much of their land in 2010, and already it’s hard to tell that it’s a new forest. Now, instead of a soybean plantation, it is the Refúgio das Araucárias and Ecovila, where they have committed to keeping 80% of the land wild. The remaining 20% is used to grow food and expand an eco-village where one can build a sustainable tiny house.

It is hard to convey how cool their story is, especially for those who haven’t lived in Brazil. But after living here for two years, I can say that doing things in Brazil is hard, especially when those things are off the beaten track. I only wish more people who owned land would see that rewilding it may be our last hope for redemption.

On their property, there’s an amazing trail. Walking through its windy path, I am reminded of the most important reason to watch birds. It’s not just for the photographic opportunities, nor is it just a game of numbers (although seeing new species is certainly enthralling). Instead, watching birds is a way of receiving ancient knowledge of ecosystems, of life, and of ourselves.

For if you spend time with birds, you can tell from the kinds of birds you see whether the land is healthy or sick, just as you can tell whether a good friend is doing fine by the way they talk and walk. This knowledge doesn’t come from science, but from a soul resonating with nature.

And walking on this trail, I feel that resonance and understanding. So, when I see two Star-throated Antwrens in a courtship dance, it’s not the rarity of the species that indicates ecosystem health. Instead, it’s the happiness of their song and their dance and their playful, unconcerned hops from branch to branch.

We enjoy our last moments in the forest. The weather isn’t great for bird photography – it’s either too sunny, too rainy, or too dark. Even so, it’s just nice to walk in this beautiful peace. The sounds of the birds and the wind in the trees are perfect.

No one else is on any of the trails. Solitude is so important, and yet the modern world is taking that away from everyone. Our desperate attempt to construct a more advanced society required a sacrifice of community and friendship, which has been replaced with advanced technology. The forest tells me there is something wrong with that.

At the end of one trail, we come to a prainha, or little beach. It is the most beautiful place because it is the farthest point into the wild that we have come. I see no birds here, but the trees are reflected in the meandering waters of the Taquaral river. And it’s just as beautiful as any bird, rippling against the smooth stones. I’ve heard that in cities, some birds sing more harshly and with less nuance because they have to compete with noise pollution. Here, the birdsong has never sounded more lovely.

We sit on the little stones and watch leaves drift by. Bursting out of the calmness, a creature is moving across the water’s surface and comes to shore. It’s a water spider, and it rests its nimble legs before darting off once more down the gently flowing stream.

Conclusion

The Atlantic Forest of Brazil is a special place. I loved every minute of being surrounded by it, and yet I was also crushed by how little of the lush, life-giving forest remains.

Throughout this trip, I also gave serious thought to the nature of wildlife photography. Is the purpose of wildlife photography to get stunning and beautiful pictures of wildlife? For me, I concluded that the answer is no.

Instead, for me, the ultimate purpose of wildlife photography can only be to bring back little experiences with birds and animals, and show that there is still something good in this world. And although I am very happy to have brought back photographs I like, knowing that this forest would last forever and expand into its former range would make me far happier than any photograph.

Amazing photos, especially of the Bananaquit / cambacica, for some reason this photo really resonates with me. The muted yellow colour of the flowery branch plays so well with the bird’s underbelly, to me it really gives off a serene and calm feeling.

I really appreciate the feedback on the photos, Nevesky. Thank you.

Thank you, obrigada for sharing these beautiful photos :)

Thank you for your comment, Shev.

Wonderful work, Jason!

That is very kind of you, Mitch!

Excellent article and inspiring photos! Brazil and especially the Atlantic Rainforest hold a special place in my heart. I think a piece of me never left. What an incredible, magical place!

I share your sentiments about what photography can be and I think it was in Brazil where I came to that conclusion as well.

Thanks, Justus. How did you come to be in Brazil? Are you Brazilian or just visiting?

I went to Brazil for a research internship in São Paulo as a biology student. Coming from a Central European, densely populated, country, Brazil and its people left me awestruck. So much so that I am now planning to pursue a PhD there.

Nice! Good luck, Justus.

Very nice article and wonderful pictures !

Thank you so much!

Lovely story. Thanks for sharing your experience!

You are welcome!

Thank you Jason for exposing your soul’s experience outside the pollution of urban civilisation.

I find also myself in many of your words and conclusion. There are times when being part of the magic given by wild nature is much more inspiring than any picture.

Thank you indeed for keeping room for this type of exploration’s pieces.

Thank you for the comment, color. Keep spending time in nature. It’s the best!

Superb and great conclusion ! Couldn’t agree more ! Thanks a lot for sharing Jason.

Thank you. I’m happy you liked it :)

Excellent, Jason!

Thank you very much!