Other Considerations

Let’s take a look at some other important considerations when photographing wildlife. We will start with animal portraiture.

Animal Portraiture

I am a very big fan of animal portraits for their difficulty and rarity. I have always imagined how great it would be to get portraits of birds and animals, similar to what we get of humans. The difficulty in something is actually what makes it all that much more interesting. Wildlife photography is a classic example of the same. We might hit a 90% mark right, but still the missed 10% could cost us a defining image.

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 360mm, ISO 640, 1/1600, f/5.6

So far I have been talking about how to pull an observer’s eye into the picture. But beyond all of that, every photographer has something very close to his heart. I love wildlife photography, because it inspires me more than even the greatest inventions mankind has made. The picture above of the rare Himalayan Thar is one of them. It has been a couple of years since I shot the image, but still can’t seize to look at it on my wall almost every morning. Very rarely does a wildlife photographer come back with the feel of “I could have not asked for more”. Never did I imagine or hope I would get a portrait head shot of such a rare and amazing animal. Bragging kept aside, let me get to a few pointers on making one:

- Immaterial of its size, portrait head shots demand us to get as close as possible to the subject. So obviously, the longest focal length probably with a suitable teleconverter is what we need in the first place.

Bengal Monitor Lizard

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 400, 160, f/5.6 - We are talking about tight crops and / or frame-filling shots here. Most of us, of course in most cases including me, crop the hell out of our pictures when the final result is sometimes close to a 100% crop. But it is not to be forgotten that, the more we crop, the more we compromise on resolution and hence the final image quality. I personally avoid cropping anything over 50%. Of course most of us do not go for prints, but even to put it in social media, too close to 100% crops will visibly show loss of quality.

Marsh Crocodile

CANON 1000D + TAMRON SP 150-600mm f/5.6-6.3 @ 600mm, ISO 800, 11250, f/6.3 - Try to be at eye-level of your subject and focus on the eye, possibly with a catch-light sharp on the subject.

Malabar Giant Squirrel

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 800, 1/3200, f/5.6 - Try to go low-key, which means having your subject against a darker background, most preferably black. A dark background also makes the entire picture moody. To get it, your subject should be at least a couple of stops brighter than the background or in other words, move around and get to an angle where your subject is across the darkest possible background. In such a case, spot metering for the brightest tone in your subject helps. This is the reason many professional photographers use back-button focusing, so that they can focus and recompose easily.

Painted Stork

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 640, 1/1600, f/5.6 - Generally, the short angle of view and tight crops in an animal portrait lack the story-telling capacity. What it lacks in story, it makes up in aesthetics. As a matter of fact, head shots demand high resolution, maximum sharpness and contrast. But sometimes, even headshots can tell stories. For example, the Eurasian spoonbill below is preparing for its nest. This is again a place where patience pays. I have seen a lot of people get close enough to a subject, click a few pictures and move on. Once your subjects allow you to enter a particular proximity, they will allow you to stay there until they feel threatened. Also, the more you stay around without harming them, the more they will trust you. Once in a while, they will display some activity like pecking / flapping feathers, stretching out, yawning, shaking off and so on. A boring headshot like the one of the black crowned night heron might be a lot less appealing than the Malabar Giant squirrel taking a meal.

Eurasian Spoonbill

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 1000, 1/1250, f/5.6

Black crowned Night Heron

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 800, 1/1250, f/5.6

Going Wide

It is no surprise that most of the time wildlife photographers, including me, tend to get to the longest possible focal length with a tele-converter attached and with a crop body. I know a lot of wildlife photographers who prefer crop-sensor camera bodies just for the extra reach and the pixel pitch. Thanks to camera bodies like the Nikon D500 that allow photographers to push ISO much higher than what we could have ever imagined a few years back, we can take phenomenal images anywhere. Obviously, with a long focal length like 600mm or above, we are eliminating a lot of unwanted distractions in the background. But sometimes, going wide brings out a whole new meaning to our photographs.

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5G ED VR @ 24mm, ISO 1000, 1/800, f/5.6

The above image is a tight crop of the one below:

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5G ED VR @ 24mm, ISO 1000, 1/800, f/5.6

Both pictures above speak for themselves. The tight crop does have all the details in the elephant and in the tree trunks as well. But the out-of-camera composition has the story that the tight crop lacks. In addition to the subject, it gives a vivid picture of the habitat to which the elephant belongs. I am certain that most photographers would agree with the fact that the story-telling capacity of a photograph would be weighed much higher than aesthetic beauty. Another example would be the picture below:

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 18-55mm VR II @ 55mm, ISO 400, 1/320, f/8

The picture above of the endangered wild asses was shot in the high altitude desert of Ladakh. It is one of the very few high altitude plateaus in the world at above 10,000 ft. I did have a 300mm lens at that point of time, but still chose to shoot @ 55mm, as this gives an idea of the arid zone that these amazing animals call home. They roam vast stretches of sand and rock, seeking scarce patches of grass.

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 18-55mm VR II @ 55mm, ISO 1000, 1/.2000, f/5.6

Another picture with yet another story. Early morning is a time when wild dogs are really hungry and they plan and strategize for the kill. They always hunt in packs as they lack the muscle power of the big cats like tigers. They take positions to ambush their prey. The picture above conveys what wild dogs are all about. Wide-angle shots work their magic on silhouette images as well (more on silhouette images further down below).

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 200mm, ISO 1000, 1/250, f/8

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 70-300 f/4.5-5.6 G VR @ 300mm, ISO 640, 1/80, f/5.6

Not always do we deliberately need to go short. It is very rare that nature rewards us with exactly what we seek. Most of the time, whether we admit it or not, it is a compromise that we make between what we want and what we get. One of the most common compromises is being unable to get enough reach. There have been many instances where I have felt even having a 500mm lens docked to a crop body, I was short of reach. Most of us tend to get the tightest crop and compromise with sharpening / saturating in post to make up for the loss of pixels and end up with an uninspiring image. Instead, we can think in the opposite direction to compose an interesting shot with what we have. The below picture is one such example:

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 1000, 1/4000, f/5.6

Me and a friend of mine were photographing raptors in Bharatpur during the golden hour, and a Greater spotted eagle was landing on a perch. I was stuck with a 300mm lens and my friend was at 600mm. But later we both loved the comparably wider image below:

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 70-300 f/4.5-5.6 G VR @ 300mm, ISO 800, 1/3200, f/5.6

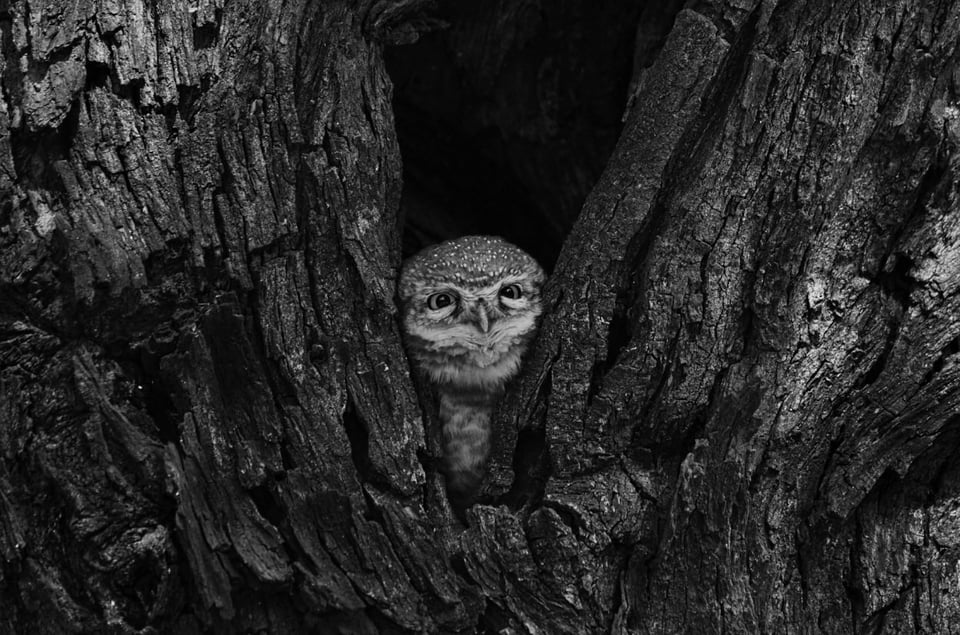

Monochrome Wildlife Photography

When it comes to giving an artistic feel, even today in my opinion, nothing comes close to high-contrast B&W images. B&W is a totally different and an endless world of creative opportunities as opposed to the saturated world we see all around us and more so on the Internet. Photography is half-science and half-art, and B&W creates unique artistic images.

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 1000, 1/2500, f/5.6

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 500mm, ISO 1000, 1/800, f/5.6

Monochrome images give room for very high contrast possibilities. With color images, there is a limitation until which bringing out more contrast ends up over-saturating the image and making it appear plastic or artificial. Also, a gray scale image gives a much calmer and deeper mood to images. In addition to high-contrast, monochrome sometimes does add more story to the image as well. Take a look at the two versions of the same out-of-camera image below:

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 480mm, ISO 1250, 1/250, f/6.3

NIKON D7000 + NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E VR @ 480mm, ISO 1250, 1/250, f/6.3

The color picture might display the vibrant color of the leopard, but the monochrome version of it tells how well these guys are camouflaged.

Capturing a Natural History Moment

I was holding the best for the last. I hope most of you would agree that capturing a unique natural history moment is what stands out as the ultimate goal in wildlife photography. It might be a blurry image of the-rarest-of-rare species like the Amur Leopard or the Snow Leopard, to capturing a unique action shot of a common subject. That is what inspires a wildlife photographer and pulls the world into the picture. It is a marvel in itself to witness life in the habitat that they were built over millennia to live in and photographing such a moment is a much higher blessing. I am going to leave you with some pictures that tell their own stories, leaving it to your own imagination and interpretation:

Conclusion

In this article I wanted to pen down the wide array of possibilities with wildlife photography. Wildlife photography has become a highly competitive world, thanks to the advancements in technology. While lenses and camera bodies were not even able to autofocus a few decades back, today even focus stacking is possible in-camera. But, irrespective of what gear we use, it all boils down to the person standing behind the camera. Unfortunately, at least from where I come from, I mostly get to see very similar compositions all over. I love looking into photographs as much as I do shooting them. Of course, wildlife does not pose for us, and we cannot go into a tiger reserve with strobes and reflectors. But with all the limitations, wildlife still has endless possibilities which most of us have ignored. As mentioned above, I live in the land of tigers and love tigers. But most of the tiger pictures I get to see are tight crops of the cat walking on the safari track. I do agree that it is not likely we get a tiger hunting shot, provided that sighting one itself is considered lucky. But most of the time we encounter wildlife, we start using our camera as a machine gun. Modern cameras can fire at 10-12 fps and have a buffer enough to shoot until we run out of storage space. But the essence of wildlife photography is to bring out the life in it. At the end of the day, only unique pictures speak loud. Thinking out of the box will reflect in our photographs and that is what the world loves to see more than the everyday clichés.

Happy Clicking!

Table of Contents