Any time you consider buying new lighting equipment, it can be a daunting decision. There are more choices in the lighting world than almost anywhere else in photography. One of the simplest such choices is also one of the most critical: should you get a continuous light or a strobe?

In this guide, I’ll take a look at the pros and cons of each type of light, break down what to look for when buying them, and examine whether continuous or strobe is a better fit for your photographic niche.

Table of Contents

What are Continuous Lights?

Continuous lights are any light source that is constantly illuminating your scene. These days, that could mean light emitting diodes (LEDs), compact fluorescent lights (CFLs), tungsten, or HMI and plasma lights. For typical lights, however, you’ll probably be considering LED or CFL based sources, as these are the most common continuous lights under the $1K mark.

CFL sources can be cheaper than LEDs, but they’re falling out of favor for high-end photography and videography compared to LEDs. LEDs last longer, allow variable color temperature, and don’t flicker. The price differences between them are decreasing, too, so my recommendation is to stick with LEDs if you need a continuous light.

Whether it’s the ever-present ring light, smaller creative RGB sources, or LED light painting tools like LED wands, there’s a huge array of other sources of continuous lighting. For this guide, however, we’ll just be looking at panels and monolight style sources, as they are the closest competitors to flash and strobe light sources.

There are many types of LED lights available for photography, from omnipresent ring lights to light-painting tools like LED wands. For this guide, however, I’m just going to cover two of the closest competitors to strobe light sources: LED panels and monolight sources.

1. LED Panels

LED panels have become very common over the last few years. These are basically just strips of LED lights arranged into a grid. They’re capable of putting out a reasonable amount of light, and are often capable of running off either a built-in battery, or a common format lithium-ion battery (or plugged into a wall outlet).

2. Monolight-Style LEDs

Next up are monolight style lights. These look more like a traditional studio strobe, but they use LEDs in place of a flash tube. Technically, these feature chip-on-board LEDs, and are therefore composed of dozens of small LEDs on that chip. But they behave a lot more like a single light source, which means they cast brighter, less diffuse light than LED panels.

What are Strobes?

Unlike continuous lights, strobes (including flashes, speedlights, flashguns, etc.) put out a single pulse of light, generally triggered by the activation of your camera’s shutter, then go dark until triggered again. By triggering just once instead of continuously illuminating the scene, strobes have a number of pros and cons compared to continuous lights.

Before diving into those differences, though, let’s take a look at some of the common form factors of a strobe. Fair warning – this section is a bit messy thanks to the lack of standardized naming, so just consider these general categories.

1. On-Camera Flash

The smallest strobes are typically the ones built into your camera. If your camera has a built-in flash, you already have access to a strobe. Unfortunately, owing to the form factor, it’s going to be limited in both terms of creative opportunities and output. It aims where your lens points, and isn’t going to be very powerful.

You can, however, use that flash to trigger off-camera flashes, whether through a built-in commander mode on some popup flashes or simply though an optical trigger. (In other words, your off-camera flash fires when it “sees” another flash going off.) This opens up some creative possibilities when combining on and off-camera flash.

2. Speedlight

The first step up beyond built-in flash is the speedlight. By separating the flash into an additional unit, you get more control over the direction of the output, more power thanks to the separate battery source, and often control over things like the “zoom” of the light or the pattern it puts out.

All the major camera brands produce speedlights that go along with their cameras, but there are also a number of third party manufacturers, like Godox, who create strobes in a similar formfactor. I’ve actually switched to the Godox V1, and will be using that for the demos later in this article, but again, they’re all really similar in terms of capability.

3. Monolights and Strobe Heads

Beyond speedlights, there are also monolights and strobe heads. These are larger, but they can put out significantly more power than the smaller speedlights. Monolights integrate the flash, power supply, and all the other bits into one unit. Meanwhile, strobe heads are just the flash, which have to be plugged into a separate power pack. Monolights and strobe heads behave similarly, but they have a slightly different form.

Compared to more basic speedlights, both of these types of strobes feature either larger battery packs or the ability to be plugged into wall power. This translates into more flash “pops” between battery changes, and often more frequent pops without waiting for the capacitors to charge.

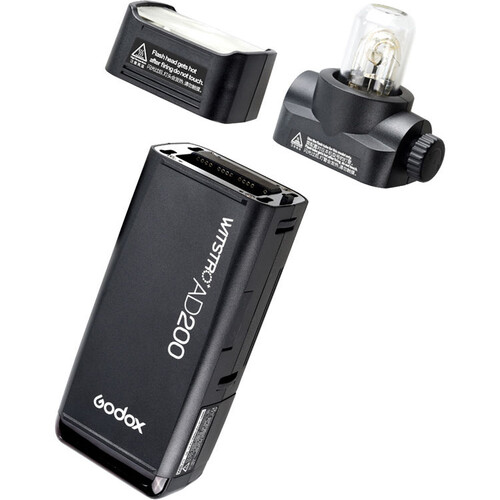

While most monolights are bigger (think breadbox sized, compared to the large soda can size of speedlights), there are a number of units that are more of a hybrid. Perhaps none better demonstrates the hybrid style than the AD200 from Godox. It has both a bare bulb and speedlight-style head, and isn’t much bigger than a camera lens.

Differences Between Strobes and Continuous Lights

Strobes can come in a wide range of form factors, but they’re all united by the temporary nature of the light. In this section, we’ll look at what that significant difference from continuous lights means for things like power per dollar, heat output, and most importantly, creative options.

1. Output

You can get both strobes and continuous lights that have a high output, but in either case, cost is going to be a major factor. A strobe will almost always be able to deliver more light, even comparing a relatively basic strobe against a high-end continuous light.

However, don’t think that you have to go strobe to get high output. High power LED sources can deliver enough light to make many styles of photography viable with continuous lighting, but they will cost more. Additionally, they will never be as capable of freezing action when compared to the very short duration of a flash.

The fastest packs, like the Profoto Pro-11, can have a flash duration as short as 1/17,500 of a second. This enables dramatic photos of splashing water, flying powder, and other effects, where even fast motion is frozen in time.

Continuous lights, while capable of putting out a lot of light, won’t match strobes for output, nor can they freeze motion to the same extent as strobes. We’ll look at some more situations where this comes into play later.

2. Heat

With modern sources like LEDs, heat output from continuous lights is far less of an issue. Older tungsten sources were nearly as good at being space heaters as they were at being lights, but modern LEDs aren’t going to warm the room to the same extent. They do still put out some heat, however, and have to dissipate it.

Some designs can dissipate this heat passively, without using a fan. Others, particularly as their output goes up, need some degree of active cooling. This means a heatsink and a whirring fan. This typically isn’t an issue for photography, compared to videography, but might still get on your nerves.

Flashes aren’t immune to heat issues either. Fire the flash too often, at too high of a power, and you may run into a thermal shutdown. To protect the system, the strobe will slow you down and give itself time to cool off. This can be annoying if it happens at a crucial moment.

Regardless of light choice, heat is a lot less of a factor than it used to be, thanks primarily to increased efficiency in the conversion of power to light. If you are looking at old continuous lights, or even older strobe systems, be aware of the potential for heat issues. But in general, don’t let it dissuade you from considering continuous lights.

3. Size

Very small continuous lights are only capable of lighting the closest scenes. Think selfie vlogs, small studio setups, and other nearby subjects. Furthermore, they won’t be able to overpower ambient light, just add some fill.

By comparison, very small strobes can still put out enough light to illuminate an entire scene. They can be bounced, diffused, or easily hidden when placed off-camera to accent particular subjects. So, if you need a small form factor – whether for portability or any other reason – a small strobe is the way to go.

With bigger lights, though, this advantage becomes less important. For example, a big monolight can throw a ton of continuous light on a scene, to the point that it’s more than bright enough for a lot of subjects. Similarly, a moderately sized LED panel can give off soft light on its own and not require big softboxes or other lighting modifiers.

4. Modifier Availability

Most lights can be made to work with most modifiers. For strobes, a Bowens style S-mount is a common style of bracket, like this Godox S2 speedlight bracket. It’s basically a ring that goes around your strobe and then attaches to your light stand. You can attach lighting modifiers directly to the bracket, or slide them into the bracket’s holder for umbrella-style rods. Whatever method your modifier uses to connect, there’s probably an adapter available.

Meanwhile, most continuous lights will support some style of mounting mechanism. Monolight-style LEDs may have something similar to the S-mount bracket, whereas LED panels tend to have proprietary lighting modifiers specific to the light in question (like barn doors or small softboxes that attach to the end). These modifiers are usually much more limited, although photographers who want diffuse light may not want them anyway, since LED panels are generally pretty soft.

If you really need to go compact, you can also use small, dedicated modifiers for speedlights. At the simplest level, these are tiny accessories like the Magmod system that are smaller than the flash itself (though usually limited substantially in their capabilities).

One last consideration for speedlights is that their smaller size can lead to harsher light even when using a modifier. This is because the light bounces around less inside the modifier compared to the large bulb of a monolight. Although you can always diffuse the flash more and more, keep in mind that your light level decreases each time.

5. Cost

Continuous lights and strobes are available at almost every price point. Basic, third-party flashes can be less than $100. Meanwhile, no-frills LED panels can be less than $100 as well.

As you move up from those models, however, you gain a lot more features. For strobes, you’ll get more power, rechargeable lithium ion battery support, faster recycle times, and more. Continuous lights will gain power and color accuracy, battery life, and support for app or remote control.

At around $250, you can get a very competent speedlight or continuous monolight. I also really like the Godox AD200 series of lights at this price point, as mentioned earlier. While slightly bigger than the speedlight formfactor, they offer about twice the power, and can even switch between a bare bulb and speedlight style head for use with different modifiers. LED panels at this price point can also be bigger and, crucially, brighter than their cheaper counterparts.

If you’re considering strobes, don’t forget the cost of some sort of flash trigger. Godox’s X System has been a solid performer in my experience, although you can also spend more on the Pocketwizard system for greater range. A cheaper option may be just using an optical trigger (plus the appropriate optical receiver if your flash doesn’t have one built in). This method does offer less control and reliability than a radio option.

Continuous lights, on the other hand, have no need for a trigger. The closest to a similar feature is that some continuous lights support a form of remote control, where you can adjust them from a distance either with a physical remote or an app. In my experience, this can be nice when adjusting a range of lights in the field.

Which is Best for Your Photography?

Trying to answer which light one should get is like answering “what camera should I get?” – it’s a question with many answers. Ultimately, it comes down to your budget, desired capabilities, and intended use. Some broad answers to this question are possible, however. I’ve narrowed down a few characteristics to consider that will help narrow down your options.

1. Motion

If you’re shooting something that moves, a flash will freeze that motion, for better or worse. While this can help get sharper results, it prevents conveying motion through blur (assuming you’re not dragging the shutter). Continuous lights, on the other hand, will make it easier to convey motion, but also make it tougher to freeze action. Some photographers use a combination of both for exactly this reason (to use a longer exposure under continuous light, then freeze your subject with a flash at the end).

2. Multiple Photographers

If you’re working with other photographers, continuous lights are easier than syncing up strobes and wireless triggers. The same goes for shooting photos around videographers. Continuous lights will look good for both of you, while strobes can be disruptive.

3. Creative Versus Easy

While I’m not saying continuous lighting is always easy, it is a lot easier to visualize compared to flashes. With continuous lighting, you can see how the light falls on the subject, dynamically adjust modifiers, and make adjustments easily by turning up or down the power, instead of having to guess or meter flash values. While some larger strobes have modeling lights, these are rarely as powerful as dedicated continuous lights.

Strobes can open up more creative possibilities, however. With the higher power output and shorter duration, it’s easier to overpower ambient lighting. This gives you full control over the light, even outdoors during the daytime. There is also more possibility for modifying light from a flash than a continuous light, thanks to how bright it is. For example, you can bounce even the most basic flash off a wall or ceiling to get diffuse light, while continuous lights are usually too dim to make that work.

4. Models

If you’re working with people, the choice of light can have an interesting effect. Continuous lighting is always shining on them, and at high outputs, can lead to squinting and awkward expressions.

Strobes, which are dark when not firing, won’t cause any of these problems. They will, however, allow your subject’s pupils to dilate. This can look unusual in extreme cases (dark studio, bright strobe look and wide eyes), but it’s definitely a more niche concern. Just adding a modeling light is often enough to knock down this effect.

5. Video Use

If you do a lot of video work or shoot both photos and videos, continuous lighting is the better investment. Continuous lights can be used for both photo and video, so you’ll get a lot more bang for your buck.

An emerging category of hybrid light, if you are shooting photo and video, is the StellaPro Reflex LED/Flash Head. This particular light works as both a continuous video light with a 92 CRI (color rendering index), as well as a strobe at up to 10 fps. It’s definitely an expensive, more niche option, but it’s a fascinating concept. I’m looking forward to seeing how this category of lights develops in the future and if there are going to be any high-quality, less expensive hybrid options on the market some day.

Conclusion

Flash versus continuous lighting is a story of tradeoffs, particularly when you dig into the products available. There are a number of great options in both categories, and I make use of both in my photography.

Strobes are indispensable when shooting a wedding, lighting dark interiors for real estate photography, or working with a compact kit. Meanwhile, I’ve really enjoyed integrating continuous lights into my product photography in the studio, just for the ease of use alone.

Whichever option you choose to start with, adding artificial light to your repertoire can advance your photography to the next level, as well as providing an exciting learning opportunity. Let me know below if you have any thoughts or questions about these different lighting options in photography!

How do i order a stellar pro reflex light

I just love the light and i was told it’s no longer in production so if i can get a used one i will really appreciate it

Thank you for this! It covered everything I needed to know :) Couple questions…Was the watch shot with a strobe or continuous? And are Strobes LED lights or Tungsten lights?

I did a lot of underwater photography and greatly preferred a continuous light source as I do above water for macro work. Underwater you lose color with depth so you only know the true color of something when you shine a light on it. With a strobe you had to “flash” the subject to know the color while the continuous source showef you the colors as you were planning the shot.

I find similar issues with macro shooting where the continuous source helps deal with reflections and evening out the light before you hit the shutter. So that is my approach though I do use a flask with candid photos of the grandkids, etc because it is just more convenient than dealing with a continuous source when always moving.

Thanks for the article.

Thanks for the comprehensive and relatively easy to understand coverage of such a complicated topic. It seems that continuous and strobe are two separate worlds in non-professional products. Are they ever combined such that a hotshoe-mounted speedlight can be bounced off a ceiling while at the same time have a forward-facing continuous LED to eliminate the racoon eyes caused by the bounced flash coming from above?

Hi SSM, usually not, since the flash is usually so much brighter than a constant LED. The LED typically won’t have much of an effect if both are used in the same photo.

That said, any effects of the LED will show up in the photo if the LED is bright enough, the flash is dim enough, or the shutter speed is long enough (capturing a lot of ambient light, and therefore light from the LED).

Excellent review, thank you Alex for your analysis, much needed as the industry still seems to be fixated on flash and strobe and less accommodating in the continuous light field. I would like to see a review of LED wands for use in long exposure photography, I see that as a very creative tool especially for stationary objects like automobiles or boats, hope you do a follow up session on wands.