I spent quite a bit of time during my youth hunting in the woods of Northeastern Pennsylvania. Along with my family and friends, I was convinced that the first day of deer season was a national holiday! In truth, I invested far more time in preparation for deer season than hunting. It was simply part of the process of being as well-prepared as possible for harvesting a deer. During my early teens, I gave serious thought to becoming a Pennsylvania Game Warden, as I could imagine no better job than being outdoors every day and getting paid for it! And although I never bagged a buck or became a Game Warden, I learned quite a bit about nature, wildlife habits, topographical maps, and many other subjects. The learning process and being outdoors was far more important to me than actually shooting an animal. When I rekindled my interest in photography, and my Nikon cameras and lenses replaced my rifles and scopes, I put many of the skills I had learned as a hunter to work in photographing deer and other wildlife.

Over the last five years, I have been photographing quite a few of the animals inhabiting Hartwood Acres, a historical landmark consisting of the former estate of the John and Mary Flinn Lawrence family, and 629 acres of pristine forest. Red-tailed hawk, whitetail deer, turkey, raccoon, and fox are regular inhabitants of the park. Rumor has it that coyotes have been spotted as well.

Despite their similarities, deer actually have very distinct facial characteristics and markings, making them easily distinguishable from one another if you are able to get close enough and spend enough time with them. I have seen some of the younger buck progress through a series of antlers from first year spikes all the way up to 12 points. I even have nicknames for some of them, such as “Almond Eyes”, in the photo below.

May and June offer an excellent opportunity to capture photographs of fawns. Having had the opportunity to spend significant time in the Hartwood Acres park (now part of the Allegheny County Park system), I can offer a few tips for preparing to photograph the upcoming springtime birth of fawns and maximizing your chances of capturing great photos of them.

Table of Contents

Deer – Creatures of Habit

Most deer are born, live, and die within one square mile. Most people, however, believe this range is much broader. This simple fact represents a major opportunity for a wildlife photographer, since, once you find a deer family, you can narrow your search to a relatively small area. It pays to explore local nature preserves, parks, state game lands, forests, and even suburban neighborhoods to identify deer activity and habits. As a teenager, I would analyze topographical maps to identify likely deer routes and bedding areas. With Google Maps, however, I can easily get an interactive view of potential deer habitat, which is far superior to that provided by traditional topographical maps.

On rare occasion, you may even zoom into Google Maps and actually see deer in the satellite image. Topographical maps never provided that level of detail! Once you find a family of deer, spend some time during early morning and evening hours in the area identifying their movements. You can also search the area to find food sources, bedding areas, lookout posts, trails, and other deer sign that will provide insights to their habits.

May Through June – Fawns Born

In Pennsylvania, fawns are typically born from mid-May through late June. Depending on where you live, fawns may be born on a slightly different schedule. Most doe give birth to two or three fawns. Once you have located a family of deer, make sure you spend some time carefully walking through the areas of heavy brush, where mother deer are likely to hide their fawns. I have noticed that areas of lush fern growth are often favorite hiding places, as they provide quite a bit of cover for the vulnerable newborns. As you walk through the area, be on the lookout for a mature doe, as she may purposely attempt to lead you away from her hidden fawns.

Good photographers (like hunters) scan their surroundings very carefully, looking at thin vertical slices of the forest, rather than the whole scene. Walk slowly and have your camera ready. Instinctively, most fawns will lie completely still and let you get to within very close distances before bolting from their bed. As they make their getaway, they will often make some high pitched “bleating” sounds! I once approached a fern-covered area, only to come face-to-face with a fawn curled up in the classic “C” position, barely three feet away. We looked at each other for a few moments, until the fawn sprang straight up in the air, nearly at my eye level, and bolted out of site. All the while, my DSLR dangled helplessly from my neck! Score: Fawn – 1, Bob – 0! Be prepared…

When You Find the Fawns and Mom Isn’t Around

Fawns rarely leave their mother’s side. But occasionally, mom needs to venture off for food or draw predators away from her offspring. Without access to affordable daycare, mother deer normally leave their newborns in a selected area, and by some communication abilities unknown to humans, inform the little ones not to follow her. Just how she does this is a mystery, as the fawns’ instinct is to follow mom wherever she goes.

When I come across a pair of fawns (rarely do I find a single fawn), I first scan the area for mom. If I cannot spot the mother, I assume she has ventured off for food and instructed the fawns to stay put. This represents a photography opportunity!

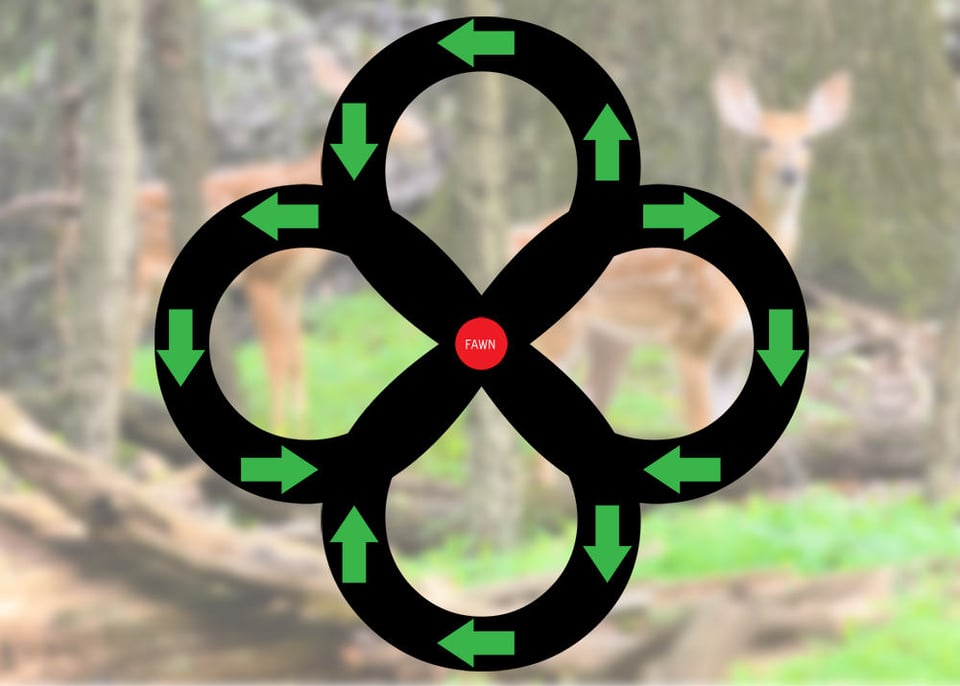

Instincts and Figure Eights

When mom has departed the scene, the fawns’ natural instinct is to remain in the same location until mom returns. This works fine until you or someone else appears to be some form of threat that might necessitate their moving. The main lesson is that fawns, even when disturbed and compelled to flee the scene, will always return to where their mother left them. This simple, but powerful rule enables you to understand and anticipate their behavior. Over the years, I have come across many fawns that exhibited this behavior. Mind you, they never run too far or too quickly, as they don’t really want to leave the area.

As such, once the fawns start moving away from you, they will do so in spurts. They will sprint 10 or 15 yards at a clip, but then pause to see if you are still following, perhaps even showing a bit of curiosity and advancing toward you at times. The best part? You know exactly where they are going – in a big circle, perhaps 30-50 yards in diameter. And then they are right back to where mom left them. If mom shows up however, all bets are off, and she can lead them anywhere to get away from you. But shy of mom returning, the fawns will continue to make large circles, always returning to the original location where you found them. Along the way, the fawns will give the opportunity to take quite a few photos, assuming you simply walk behind them at a relatively slow pace.

I have often followed fawns around in circle so many times that I have given up, sensing their frustration and just plain exhaustion of my “chasing” them for the better part of an hour or so. Throughout each cycle, I have often seen them anxiously looking around for mom to come back and save them from the crazy guy with the camera that is simply not content to leave them be!

Summary

Although I no longer carry a rifle when pursuing deer, many of the hunting lessons I learned have yielded benefits in the area of wildlife photography. The willingness to understand animals’ habitat is critical to improving the opportunities to get close to wildlife on a regular basis. Understanding where to look for fawns during these upcoming critical months, and anticipating their instinctive behavior can mean the difference between taking run of the mill photos, and capturing a series of high quality wildlife pictures that you will treasure for a lifetime.

I was checking out riverbottom during this ice storm and an eye to eye moment with a juvenile bobcat in its den through binoculars was final straw I’m not gonna kill another living thing again. after 30 years away from it 2 years back into it hunters have got dumber deer got smarter. This generation “huntn” is atvs. corn, boxes in sky and corn. I’m buying a camera and gonna shot record bucks with it. these generation of hunters are the kids of 1st atv owners so it’s part of hunting to them but in the south the land is destroyed and pines planted so deer have to live in that crap add pigs and people pay $10,000 to kill a buck in a fence. that’s not hunting thats killing. so even tho I love eating deer I can do without .

Dustin,

Hunting has certainly changed since I got my first license. That said, someone still has to cull the herd each year, and I’ll always support those that choose to take on that responsibility. In my case, however, I realized I wanted to be around/close-to the animals, so a DSLR with a long lens, and the opportunities to visit areas with plenty of wildlife (local parks and cemeteries) satisfied my needs.

Bob

I hunt but love taking wildlife pictures. I really dont look at killing a deer that way. type can make it sound very ugly but in reality if you have meat in the freezer then arnt we being a hypocrite. Harvesting a deer for meat is no different than going shopping.

Very nice article Bob! Thanks for sharing. Looking forward to your future ones.

Jeff,

Thanks for taking the time to comment.

Bob

Lovely photos. Wild deer look stunning against a winter backdrop too :)

Alpha,

Indeed. Love your pictures! You have some stunners in your collection.

Bob

Here are the picture settings:

Picture 1 – Buck – Nikon D300 and Nikon 70-300mm VR

Fawns – Nikon D7000, Nikon 70-200mm VR II with Nikon 1.4 T/C – ISO 1100 – 1600

Hunter with Rifle – early Kodak EasyShare digital camera

Running fawn settings – Shutter speed – 1/100, ISO 1100, f/5.6, 280mm, Nikon D7000, Nikon 70-200mm VR II with Nikon 1.4 T/C

Thanks for the comments everyone. While I don’t hunt anymore, I remain a strong advocate of hunting. The real “villains” of wildlife are not hunters, but rather urban sprawl that continues to destroy woodlands, and the simple fact that we have killed off the natural predators of the deer (funny how people get rather “touchy” about wolves, bears, and coyotes showing up in backyards where their toddlers play!).

As a result, the deer have less food supply and areas to inhabit, but continue to expand their population. As their ranks swell, they become a serious danger to motorists on highways and local roads. In areas where they have outlawed hunting, deer either starve or succumb to diseases – nature’s two most common methods of controlling populations. If shooting a deer seems cruel, it would seem that starving, dying slowly of disease, or getting hit by a car and limping off to the woods to eventually succumb don’t appear to be “kinder” alternatives.

Hunters perform a valuable service by controlling animal populations, and funding quite a bit of research and land management that benefits wildlife populations. While some people advance a rather stereotypical “hickish” view of hunters, the vast majority of hunters are extremely ethical, and care deeply about wildlife and nature. And you are far safer in the woods on opening day of deer season than you are on the streets of some of our major cities!

As my wife can attest, I have a real soft spot for any type of animal. I have been banned from stopping by animal shelters over the last few years, as I cannot seem to visit one without bringing home another pet! At the same time, I realize that the deer population that not kept at a manageable level by hunters, eventually suffers greatly in ways most people never witness.

In short, there is nothing inconsistent with caring deeply about wildlife, and supporting hunters that keep the animal population in check.

I appreciate you taking the time to educate and inform regards both sides of the coin. Both can be honorable endeavors. Thank you

www.dpreview.com/galle…990/weseeu

Eric,

Not sure I will convince anyone, but I do feel strongly about it, particularly since I hunted since I was 13.

And that is one heck of a photo! Quite a huge rack on a huge deer! Thanks for sharing.

Bob

Great info….but don’t forget about ticks. Any where deer are so are the ticks and lyme disease and related illnessess can be devastating.

Lynne,

Indeed, I often forget about ticks, but you are correct. People should use the nylon “gaiters” that cover their shoes and extend upward to their knees.

Bob

All I can say is – I’m glad you put down your weapon and starting shooting with something else. Nice shots!

Oded,

It is certainly more enjoyable than hunting, although they do allow archery hunting in the area. And while I have been accepted as one of the “herd”, and developed quite a few new “friends”, I realize that hunting is indeed necessary, as the deer population would continue to grow unchecked and result in starvation, disease, and deer increasingly traveling across roadways and into oncoming cars, in their search for food sources.

Bob

Wow, the running fawn picture is just wonderful. Could you please tell us what lens and shutter speed you used on this one?

Thanks,

Eric

Eric,

Thank you. Please see below.

Bob

I was happy to learn you surrendered your rifle for a camera. Capturing the beauty of an animal is far more rewarding than killing.

Coast,

I can actually get much closer to wildlife and have a more enjoyable experience with my camera than my rifle, but I a not an anti-hunter by any stretch. When you can get so close to a doe with your Nikon 70-300mm VR, that you have to back up to enable your lens to focus properly, there are few experiences in the hunting arena that can beat that! :)

Bob