I believe it was Cartier-Bresson who said that your first 10,000 photographs are your worst. For many hobbyist photographers, myself included, it may be much more than that, as improving our craft means constantly shooting, experimenting, reassessing, and continually culling our very best from our best.

See more photos from the series here.

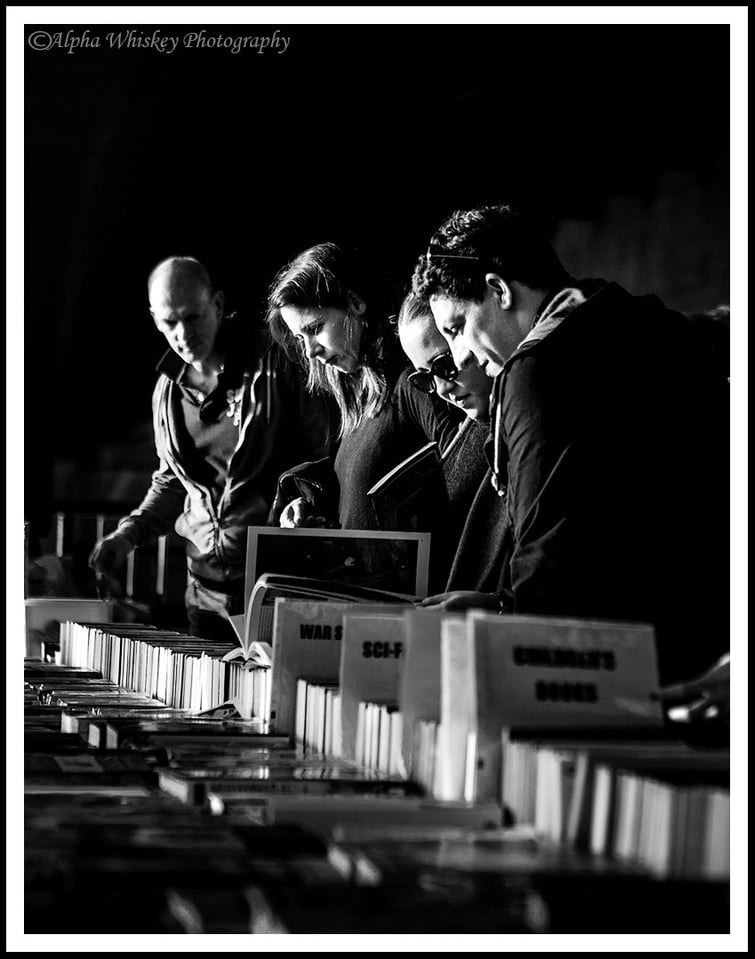

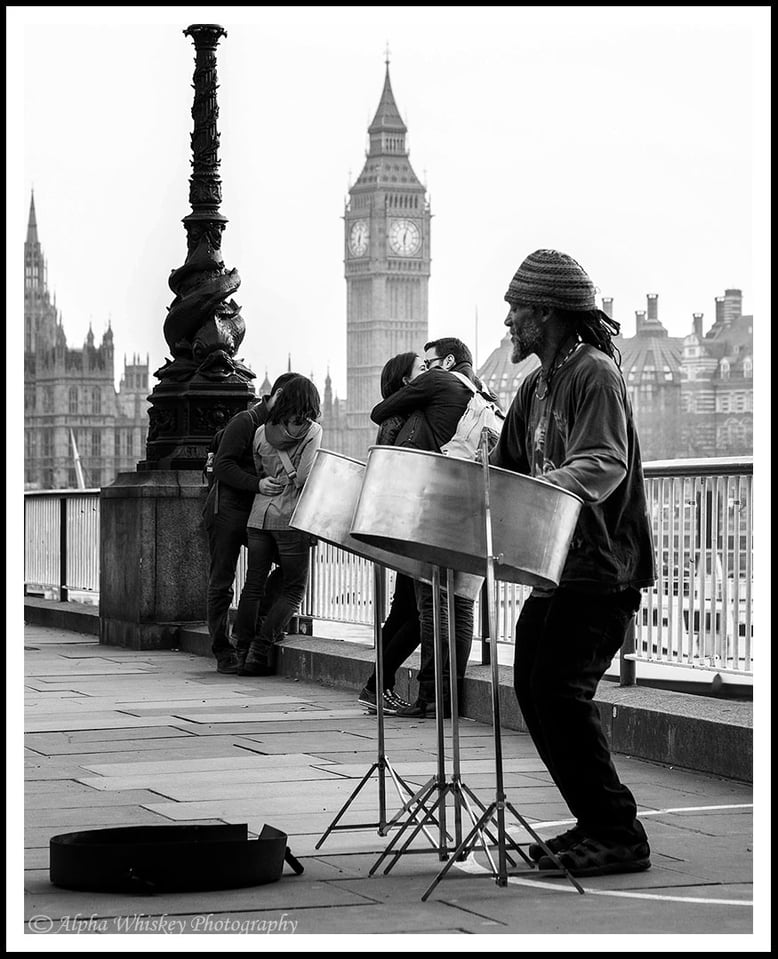

Many photographers will subscribe to online challenges of capturing a particular subject each week or month, and yet they largely fall into a trap of capturing a subject simply because it is there and then uploading it to the benefit of the site that set the challenge. Rather than improve their own skills, they have merely added to the inventory of someone else’s site. It has been said that a good photographer captures, while a great photographer reveals. However, it is only a few that truly reveal something original or creative.

It does often seem as though many of the amateur photographers today have more of a gadget fetish than a desire to improve their photography, preferring to know more about such things as pixel density and corner sharpness than composition or lighting. Indeed, despite deliberately not preaching any technical nor photographic expertise, I have been sometimes been attacked by people who have little to show for their vitriol other than pictures of their gear!

I write this with all the humility of a hobbyist, and with only the intention of someone trying to help. My blog is a catalogue of my attempts to improve my own skill. Because I accept that I myself capture more than I reveal, I am always challenging myself to improve my ability to see, the foremost skill I think any photographer should have.

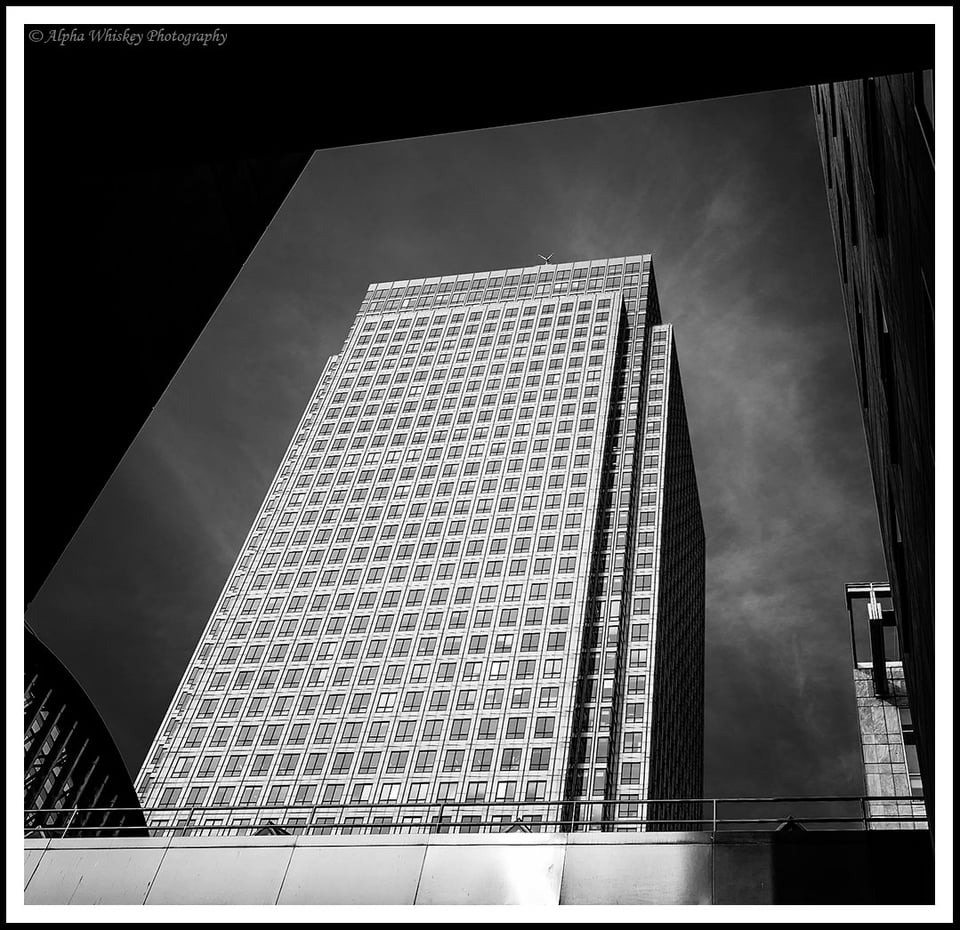

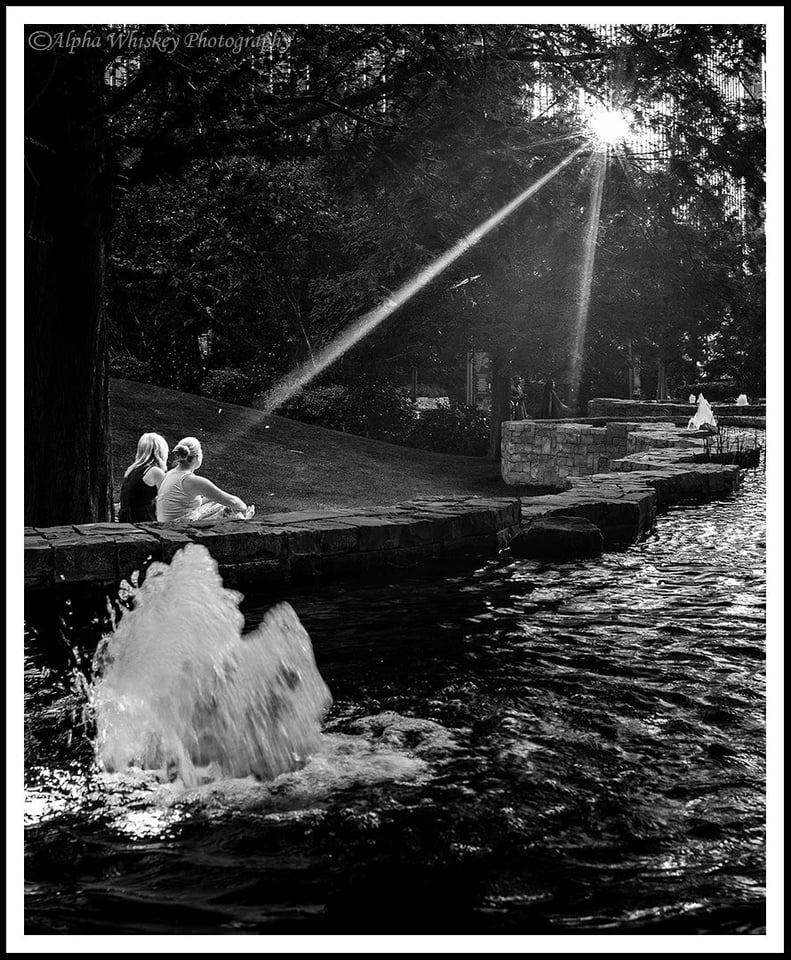

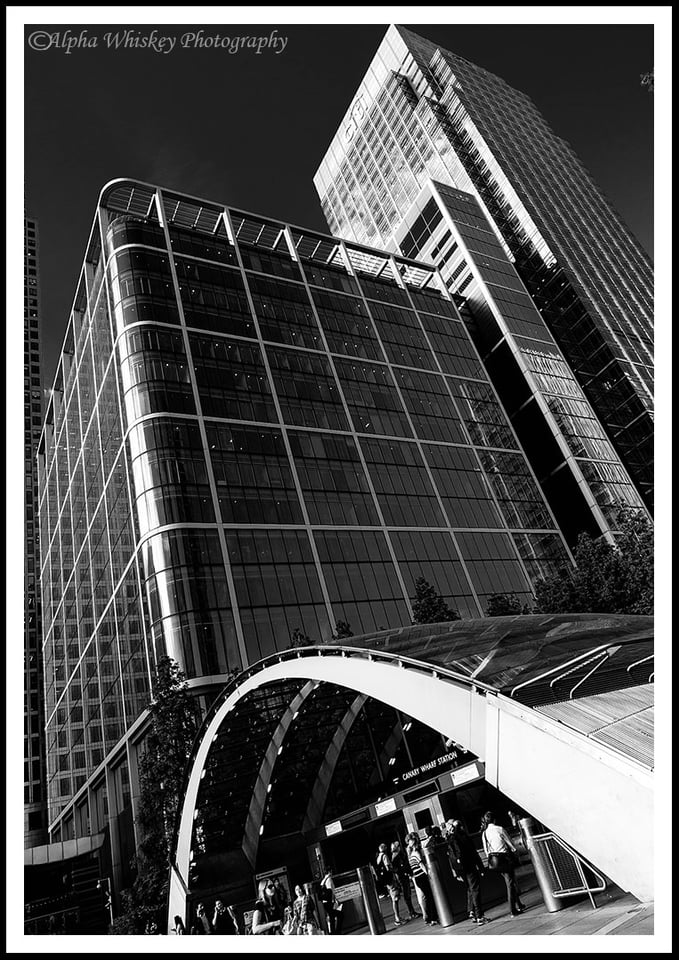

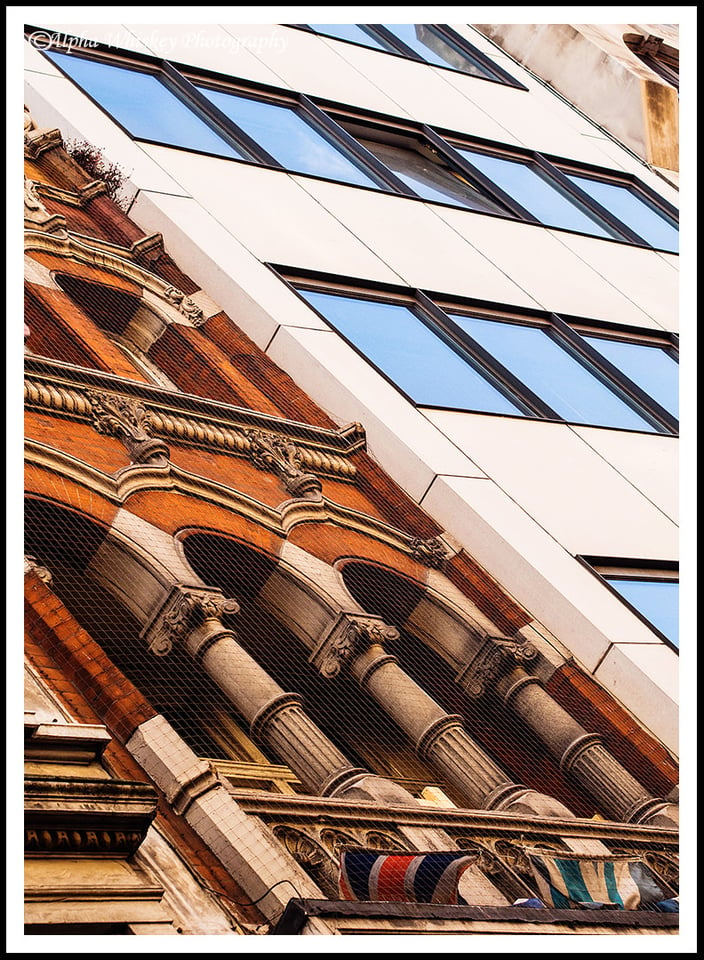

Our images will never improve by simply upgrading our equipment and hoping they deliver results for us. We need to think about our composition, framing, timing and light. Deconstructing our subject into its constituent shapes, colours or shades and understanding how they juxtapose and relate to each other will yield stronger and bolder images, whether they belong to building or cars or nature. Even portraits can make creative use of light and form to highlight features or anatomy, or to enhance beauty or tell a story.

One of the ways in which I attempt to improve is by setting myself (along with friends and fellow photographers who join me) real challenges. We will often limit ourselves to taking only a few shots, say 20-30, and perhaps with only one focal length (prime lens). This kind of restriction forces us to slow down and see the world differently, and to look for compositions in ways and places that we may not have considered before. It encourages us to properly frame a scene or subject, leaving out anything superfluous. With only one focal length, our feet do the zooming rather than the lens. This can train us to get into better positions and have better spatial awareness.

Being limited in how many times we can press the shutter forces us to consider whether an image is really worth taking. The luxury of digital is that we can spray and pray but by limiting the number of shots, as in the days of film, we have to take our time to really look for something interesting to shoot. The result is hopefully fewer, but stronger, images. Have the courage to limit the number of images you decide to shoot on your next excursion or vacation, and you are sure to return with a smaller batch of more impressive photos.

You might argue that we could restrict ourselves even more in this regard, to perhaps only 10 or 5 images. And this is perfectly valid. But I believe one of the skills a photographer also needs to develop is the ability to select their best images from a batch, i.e. to continually edit their portfolio. Taking more images affords one the scope to exercise this process, until with time one is confident enough to take fewer images in the first place.

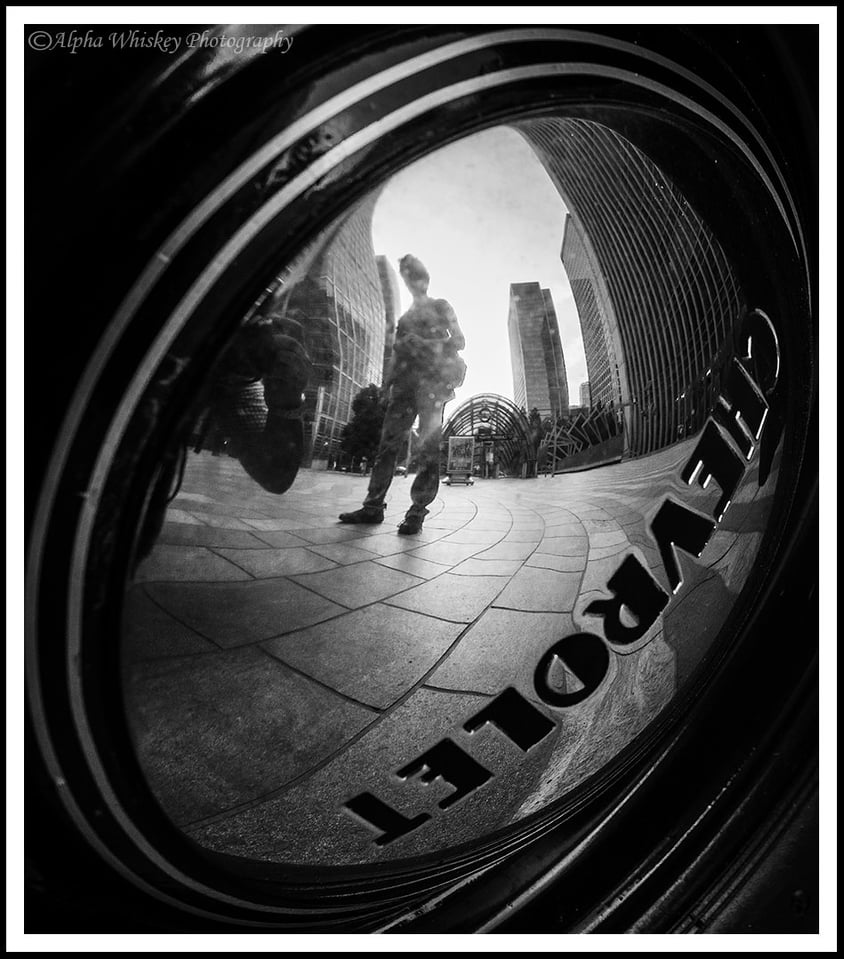

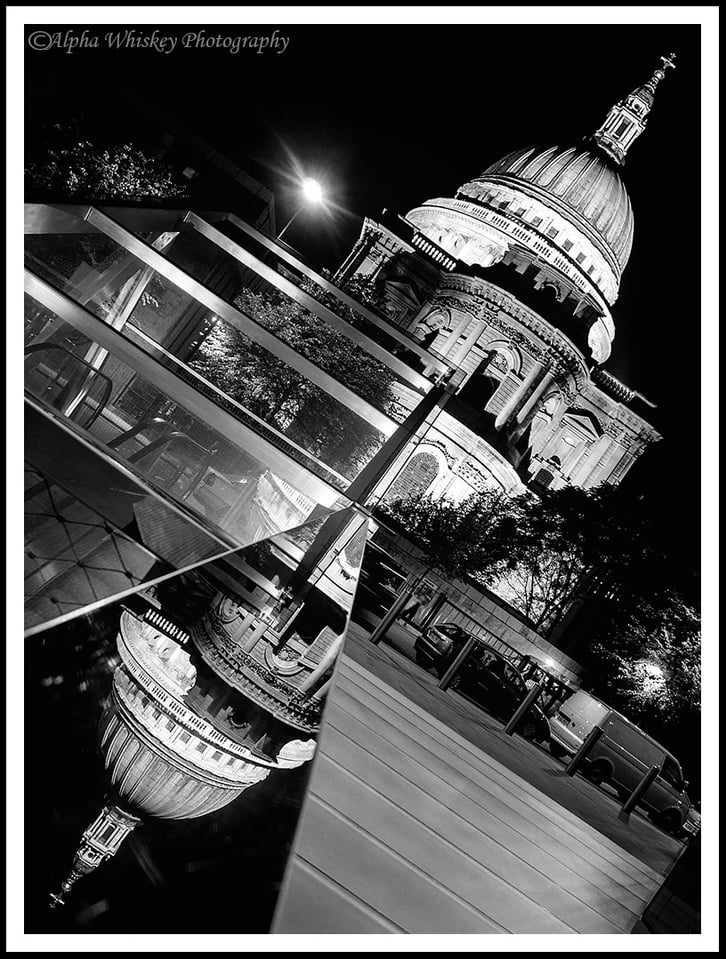

Often on our photo challenges, we decide that our images must be black and white, either at the point of capture (if using a B+W filter on the camera) or later in the editing process. This makes us imagine the scene without the distraction of colour, reduced to its basic elements or shapes, and then consider its merit as a photograph. Does it offer something abstract with its shape or lighting? Or is the scene telling a story that would hold interest even without its colour?

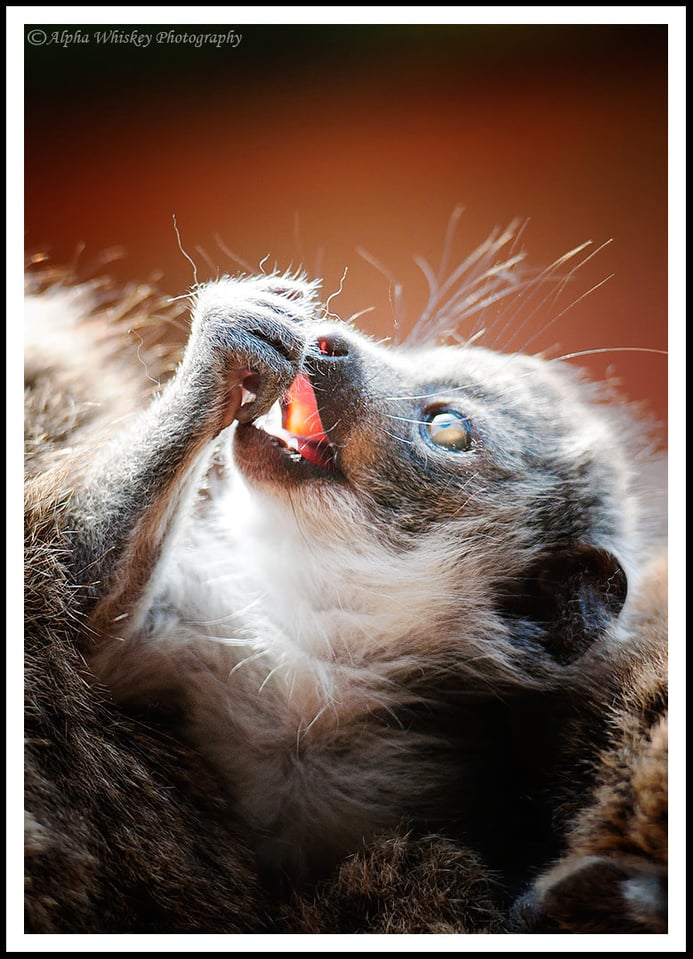

All of these limitations serve to improve our visual radar for an interesting shot, hopefully revealing something new to us. While it is true that our photo challenges have mostly been street photography or cityscapes, the improved skills can surely be applied to any subject. Indeed, when photographing animals, either in the wild or captivity, I will take my time and patiently wait for an engaging moment. It is not enough to simply photograph the animal because it is there. I try to engage the viewer with the animal in a more intimate way.

I have shot around London countless times, and each time it becomes harder to reveal something new and original, especially when shooting somewhere I have shot many times before. But perhaps this is also part of the challenge. A good friend in New York, to whom I regularly send my photos and who has visited London many times himself, observed that I often make the ‘familiar unfamiliar.’

And perhaps this perfectly sums up the challenge we should all set ourselves. With the billions of images taken everyday of so many familiar places and things, we should all aspire to reveal something different about them, rather than simply capture them because they are there. And I am afraid that this is ultimately a skill only we ourselves can develop, regardless of our gear.

Alpha Whiskey hello

I read a lots of posts and yours really struck a chord . Very thoughtful and elegantly explained. The two insights of ”revealing something”and making the ”familiar unfamiliar ” was very inspiring and gives me something to shoot for. Living in a big city and seeing your shots of London challenges me to find something fresh in a sea of same old buildings and tourist attractions.

Thanks for sharing it.

Thank you Lancej. I am most pleased that you liked the article. :)

Regards,

Sharif.

like most new photographers we get use to zooms then we try a prime lens then we have to learn how use a fix focal length. I know that sounds odd but like I was taught frame it and get it right in the camera so instead of standing and zooming now u have to move around and try to capture the photo u wont. so that’s how I challenge my self I stick a prime on and walk around to find things to photo. if u don’t believe me try a 85mm prime as a walk around lens sometime or if you have a Nikon DX a 50mm lens

Great article Alpha Whisky.

People’s focus on gear and numbers bothers me to no end. Usually, after a shooting people ask me what camera I use. Never what settings and why, it’s always the gear.

I’m using a d́800 with Nikkor lenses, but looking at the photos I’ve taken in the last 2 years with it, I can say that at least 50% of all photos could have been taken with any DSLR, even with the cheapest entry level APS-C + kit zoom combo (with some care and thought). For the remaining 30-40%, you’d need a broader selection of lenses, but still, could have been taken with any camera. It’s only 10-20% of all the photos I took that having the d800 was clearly an advantage. And the difference is quantitative, not qualitative. For example, I probably get 20% more shots in low-light events than I would with my old d7000, but they are not the top 20% in terms of quality.

There is just so much more going into a shot than gear, and it’s good to have articles like this. In fact, nowadays I’m having fun using all kinds of cameras (even cheap point & shoot zooms) because they make you think harder, and that’s what matters – the thought, the idea behind the shot.

Thank you for the wonderful article.

Thank you Csaba for the positive feedback. I echo everything you say :)

Warm Regards,

Sharif.

Limiting yourself to a few photos is the key. I didn’t realize this until I started shooting medium format film. When you are limited to 10-16 shots on a roll (with the hassle of changing rolls), then you really start to think about how to use each frame. The beauty is that after shooting film for a while, it has transferred over to my digital shots as well。I now shoot far fewer frames in digital and am constantly deleting all but the best. Your article really rung a bell with me. Now I just need to concentrate on ‘revealing’ instead of ‘capturing’.

Me too, Eric! Thanks! :)

Why must photography always turn into a right-wrong and this-or-that debate, with absolutists making sweeping, broad stroked statements.

I don’t know why it’s turned into a contest between light/composition and technology/equipment. I don’t see where any of what you said – “PL about microcontrast, resolution, sensors, noise, corner-to-corner sharpness, lens sharpness, HDR, focus stacking, and blah blah” – cannot co-exist with, and further enhance, traditional and well-proven techniques established by the greats of yesteryear, ie. Cartier-Bresson and others.

With all due respect to Alpha, who’s work is superb, as King Solomon once wrote: “…there’s nothing new under the sun…” Alpha hasn’t invented fire or the wheel and he’ll be the first to admit it. Hence, there’s not much to beat our chests about.

This is the first time I’ve been back to this site in months, and nothing’s changed “under the sun”. It’s more of the same type of discussions where it’s either ONE OR THE OTHER but hardly ever BOTH. First, the sweeping statement made a few months back that full-frame would kill off smaller formats, followed by the pronouncement of the certain death of the DLSR at the hands of mirrorless.

Yet, Canon just spent a fortune pimping their DSLR line through the Wold Cup’s bottomless advertising outlets; and this very site has taken the driver seat of the micro 4/3 bandwagon and the bloggers have recognized the merits of smaller formats.

Do you think that we can ever get to the point where it’s ALL GOOD and ALL OF IT can co-exist in the photography world without us having to set limits of right/wrong, better/worse?

Hi JR,

Let me indeed be the first to admit that I haven’t said anything new or invented the wheel :)

And I, like yourself, do not like or take absolutist positions on these things. I hope I have simply articulated thoughts that many people may already have. I believe you make a valid point, and I have stated in my previous article that how we capture the images does indeed depend to a large extent on our technology. So yes, the equipment is important. But I also believe that technique and the rules of composition etc, which haven’t really changed since the dawn of time, are probably more essential to the art of photography than temporary iterations of equipment, or the minutiae of their performance. In the right hands and with good technique, perhaps any/most cameras/lenses would produce appealing images. The common denominator is the photographer him/herself. :)

As a former user or DSLRs and current user of m4/3, I absolutely recognise the value and advantages of both formats. For now, and speaking only for myself, the m4/3 format suits me for most of my photographic endeavours, and in no small part because of its lighter profile. But I’ll categorically state here and now that all formats, DX, FX, m4/3 and others have their respective places. As you correctly pointed out, the economics alone are proof of that. :)

Warm Regards,

Sharif.

well said … and beautifully illustrated!

Thank you Lois! :)

An excellent article, Mr. Alpha Whiskey. Thank you.

I wonder where all of the pixel pushers, test chart shooters, and arm chair photographers who’ve been ranting and raving on PL about microcontrast, resolution, sensors, noise, corner-to-corner sharpness, lens sharpness, HDR, focus stacking, and blah blah with nothing to show for it have gone? You guys (and gals) are awfully quiet right now, aren’t you? Let’s hear from you!

Haha! Good point! And thank you! :)

Great article and those photos that you used not only are very good, but helps to drive home the idea behind the text.

As an aside, I have found that for me is experimentation through multiple approach angles rather than limiting myself to a low amount of shots that really works, but I believe that is because I take the time to analyse the hundreds or even thousands pictures I can get away, studying what did make or break each shot. And this process is usually that tedious only on my firsts attempts at each subject, and with time I’m shooting less and less, but consistently producing better shots.

But I agree that for most people thinking before the fact may be a better idea.

Sharif,

Have you ever tried to capture lightning in the clouds at night time? When the lightening is strong you can see it spreading out in the sky, but mostly it stays within clouds. So white clouds emanate a wonderful array of colours when a lightening jolt makes them glow, especially at night. I saw such a scene last night and was equipped with a d5100 and a 35mm lens but night time exposures are tough, the camera does not autofocus mostly. maybe with a tripod and a long exposure, itcan be done?

Hi Muhammad. No, I have not yet tried to photograph lightning, although I would love to give it a try. It’s on my list! :)

If you’re far enough away from the storm then I guess manually focusing to infinity or just before it would be fine. And yes, a long exposure would probably be your best bet to capture the lightning strikes as they are impossible to predict :)

Cheers,

Sharif.

Sharif

Once again thank you for a wonderful article. Photography is something is something that has to come from within and thus if you are passionate about that hobby then you will improve because that is what we love to do and practice makes perfect. Photography is all about looking at the world a little differently than what we perceive ordinarily, and yes it not about capturing but revealing, some of the most common and ordinary things have something special about it and to reveal that is what photography is all about. One must not get caught in the rules though the rules are important, but still one should frame the shot in their mind first then use the camera to capture it. Rightly pointed by you that many photographers nowadays are all about the gear and gadgets and less about shooting. I do not restrict myself by gear limitation, I took up photography at a very young age then I used to take pictures with my mother’s Kodak film point and shoot camera, then started shooting with my phone, then got a budget point and shoot camera and recently moved to DSLR and I must say all the years of shooting with point and shoots and mobile phone has taught me a lot and am now learning more with a DSLR and have also taken some images with my maternal Grandfather’d Agfa Isoly film camera which is still amazing. I still for general shooting use the kit lens which came with the DSLR and I must say it is a good lens, thus it is the photographer who is important and not the gear as the camera is only a tool to capture what the photographer has visualised in mind. Thus photography is all about learning and improving and to improve one needs to practice. Today we have the luxury to take as many shots as possible due to digital thus we can practice a lot which was not available to people who used to shoot with film, but still we can limit our shots and get good images in this age of digital by thinking of it in this way that the shutter that we have in our DSLR has a life of a certain number of shutter releases thus making it a limiting factor and not reducing the life of the shutter as replacing a shutter is costly. Thank you for the article.

You’re welcome Zeeshan :)