Lenses. They’re arguably the most important piece of equipment a photographer can buy – even more important than the camera itself. But what makes lenses so useful? Why are some camera lenses so much better than others? The answer goes beyond simple things like sharpness and image quality. Instead, lenses matter because they control which photos you can even take in the first place.

Table of Contents

1. The Anatomy of a Lens

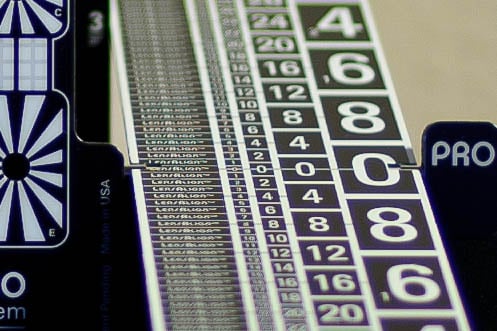

Modern lenses look something like this:

Each part of the lens serves an important purpose:

- Filter thread: Lets you attach lens filters to modify light that reaches your camera sensor

- Front element: Collects light and bends it to the other lens elements

- Lens hood thread: Lets you attach lens hoods to block sunlight and reduce flare

- Zoom ring: Rotates to zoom the lens in and out

- Focus ring: Rotates to focus manually; does not rotate when camera autofocuses

- Lens name: Identifies lens

- A/M switch: Switches between autofocus and manual focus

Not every lens has all seven of these features, and other lenses have many more than this. However, the lens above is fairly representative of modern zoom lenses.

2. Camera Lens Terminology

Most lenses today are named in a relatively standard way:

- Brand name, lens type, focal length (in mm), maximum aperture, other lens features/abbreviations.

For example, the official name for one of Nikon’s professional zooms is the “Nikon AF-S 24-70mm f/2.8 E ED VR” lens. Canon’s equivalent is the “Canon EF 24-70mm f/2.8 L II USM” lens.

The most important terms are focal length and maximum aperture. In other words, the “mm” and the “f/number” terms. These numbers are the most directly related to the types of photos you will be able to capture with the lens. (I’ve got a full section later on each one and why it is so important.)

What about the abbreviations at the end of the lens name? They still matter, denoting the extra features offered by each lens. For example, the “VR” term in the Nikon lens stands for “vibration reduction,” which stabilizes the lens for handheld shooting. However, these other terms are usually secondary in importance. Some don’t even refer to a specific feature, but instead are solely for advertising value (such as “L” on the Canon lens, which simply means it is one of Canon’s high-end lenses).

Thanks to this telephoto lens’s vibration reduction feature, I was able to handhold it at 1/40 second and still capture a sharp photo.

The main exception to the “mm and f-number matter most” rule is when you’re dealing with specialty lenses. With fisheyes, macro lenses, tilt-shifts, and so on, your main reason for buying the lens has more to do with its unique feature than anything else.

So, what do all the abbreviations at the end of a lens name stand for? Each company labels its lenses in a different way, with potentially dozens of abbreviations per manufacturer – too many to fit in this article. However, we’ve covered all the various terms for many lens manufacturers the following guides:

- Nikon lens abbreviations

- Canon lens abbreviations

- Sony lens abbreviations

- Fuji lens abbreviations

- Sigma lens abbreviations

3. What Is Focal Length?

The most important specification for most lenses is their focal length – in generic terms, how far “zoomed in” the lens is. Focal length is written in millimeters.

Some lenses only have a single focal length. These are known as prime lenses. A popular example is the 50mm lens – a very common first prime lens for photographers, thanks to its high usefulness and low price.

Other lenses are zoom lenses, meaning that they cover a range of focal lengths. For example, the most common zoom lens on the market is an 18-55mm kit lens (sometimes 18-50mm or similar). These lenses zoom from a relatively wide angle (18mm) to a moderate telephoto (55mm). If you divide the lens’s longer focal length by its wider focal length (like 55/18), then you get the lens’s zoom ratio (like 3x).

Also see our article primes vs zooms.

A few specialty lenses on the market fit somewhere between primes and zooms, such as the Leica 16-18-21mm f/4 lens. This lens covers three specific focal lengths – 16mm, 18mm, and 21mm – but none of the focal lengths in between. This is contrary to a normal zoom lens, which smoothly zooms from its widest to longest focal length.

The technical definition of focal length is a bit messy, and beyond the scope of this article. Elizabeth wrote a comprehensive guide to focal length that explains everything at a technical level.

We also have full articles introducing wide angle lenses and telephotos.

3.1. The Impact of Camera Sensor

I’ll note quickly that the sensor size of your camera contributes to the apparent focal length you’re using. This is because small camera sensors are like crops from a large camera sensor. Put the same lens on both, and the lens will appear more zoomed in on the small sensor.

Cameras with a larger crop factor (i.e. smaller sensor) will exhibit this effect the most. You can calculate the exact amount simply by multiplying your lens focal length by your crop factor. So, an 18-55mm lens used on a Nikon DX sensor – which has a 1.55x crop factor – is equivalent to a 28-85mm lens on a larger full frame camera sensor.

This is also why you can’t just say that a 28mm lens, for example, is a wide-angle. On some cameras, it is more like a medium lens, and on others it’s even a moderate telephoto. You have to specify 28mm equivalent.

Here’s a general guide:

- Wider than 35mm (equivalent): Wide angle lens

- 35-70mm (equivalent): Normal lens

- Longer than 70mm (equivalent): Telephoto

Anything wider than 18mm and longer than 300mm is generally considered an ultra-wide or a super-telephoto. (On Nikon DX and other APS-C cameras, that would be wider than 12mm and longer than 200mm.)

All of these are rough figures, though. Some photographers may consider 35mm to be wide angle rather than normal, or vice versa, and it’s not a big deal either way.

Taken at 17mm. Since I used a DX camera (the Nikon D7000), this is only a moderate wide angle. On full frame, 17mm would be ultra-wide.

4. What Is Maximum Aperture?

The other critical term in a lens name is the “f/number” term, which stands for the lens’s maximum aperture.

First, if you are unfamiliar with the concept of aperture, I recommend reading our beginner’s guide to aperture. In short, aperture describes the “pupil” of your lens. Just like the pupil in our eyes, the aperture in a lens will let in more or less light. It is quite an important specification.

Many photographers don’t realize that aperture is written as a fraction. This is why f/2 is larger than f/4 – it’s just like 1/2 being larger than 1/4. Expensive lenses often have large apertures to let in a lot of light (again, like a large pupil). For that reason, a 24-70mm f/2.8 zoom is going to be more expensive than a 24-70mm f/4 zoom in practically every case.

In general, prime lenses have a larger maximum aperture than zooms, especially at a given price. It’s one major reason why photographers use primes. Zooms usually max out at f/2.8, while plenty of primes on the market go to f/1.4 and sometimes wider. This means prime lenses can let in 4x as much light as the best zooms.

Of course, even though a lens name will include its maximum aperture, you aren’t restricted to using that aperture alone. You can always change the aperture to be smaller if you want. Almost all lenses go down to at least f/16, while many allow f/22, f/32, and beyond. This is called minimum aperture.

Minimum aperture isn’t nearly as important as maximum aperture, though. It’s why you only see maximum aperture in the lens name. If you use extremely small apertures, especially f/22 and beyond, you start to add blur throughout your photos and darken them more than you’d normally want.

As with focal length, here’s a general guide to aperture:

- Wider than f/1.4: Extremely large aperture

- f/1.4 to f/2.8: Large aperture

- f/4 to f/8: Normal aperture

- f/11 to f/22: Small aperture

- Narrower than f/22: Extremely small aperture

4.1. Depth of Field

The other reason why maximum aperture is so important is that it impacts your depth of field. Large apertures like f/1.4 and f/2.8 will give you more of a “shallow focus” effect, where the background is blurred and your subject is sharp. This is very common to see in portraiture and still life photography.

Depth of field is also influenced by the lens’s focal length. Telephoto lenses have a shallower depth of field than wide angles. So, if you really want to blur the background of your photo as much as possible, you’ll want at least a 50mm f/1.8, and probably something like an 85mm f/1.8, 85mm f/1.4 or 105mm f/1.4. But those lenses also get progressively more and more expensive.

4.2. Variable Aperture Zooms

Some zoom lenses have a different maximum aperture at their wide angle and telephoto ends. These are called “variable aperture” lenses. For example, the 18-55mm zoom I talked about earlier usually is f/3.5-5.6 variable aperture. If you shoot at 18mm, you can use an aperture as wide as f/3.5. If you shoot at 55mm, you can use an aperture as wide as f/5.6. (At focal lengths in between, your maximum aperture gradually changes from f/3.5 to f/5.6.)

Variable aperture lenses don’t have the best reputation. In part, this is because it is annoying to have different aperture limitations throughout the zoom range. But all lens designs have trade-offs, and variable aperture is hardly the worst compromise out there.

In fact, these lenses can be smaller and less expensive than constant aperture zooms, making them quite reasonable in many cases. So, don’t avoid variable aperture zooms by default. Instead, look to other features of the lens, too, to see if it’s a good fit for you.

5. Important Lens Features

When I buy a lens, I don’t look at image quality first. Instead, there are other factors which matter more.

First: size and weight. I’m willing to give up some image quality – as well as things like zoom range and maximum aperture – to get a lighter weight lens. Of course, finding a lightweight lens can be a bit deceptive. If one heavy zoom lens replaces three moderately heavy primes in your kit, the zoom isn’t really heavy at all. Or if two lenses are equal in weight, but one goes with a lighter camera system, it’s still got the advantage.

On top of that is autofocus. Not all lenses have autofocus, and not all autofocus lenses are equally fast and accurate. It doesn’t matter as much to some genres as others, but if you’re a sports photographer, chances are good you’re willing to pay for top-notch autofocus performance.

There are tons of other lens features that matter in photography. A big one is durability/weatherproofness. If you can use your lens for several years in tricky conditions, it’s worth much more than a lens that can’t handle being bumped around.

The overall ergonomics of the lens also matter quite a bit. This includes everything from the position of the zoom ring to the smoothness of the focus ring, and how seamless it is to use the lens. You might not notice lenses with good ergonomics, but you’ll certainly notice bad ones.

And, naturally, all of these factors tie into price (same as the next section, image quality). As nice as the Zeiss Otus lenses might look to you, it’s probably more reasonable to go with a Nikon or Canon lens that fits the same focal length.

5.1. Construction

Of all of these concerns, one of the most important and easiest to overlook is simply the lens’s construction. Lenses with the fewest number of moving parts (i.e., internal focus and internal zoom) are generally ideal, since it allows for fewer points of failure. The same is true for lenses which are weather sealed; it’s worth paying more for a lens that will last longer.

I’ll also mention the distinction between metal vs plastic lens construction. Typically, metal lenses are seen as higher-end and may command a higher price because of it. However, I personally prefer high-quality plastic lenses instead. They weigh less, deal better with bumps, and don’t get as cold in bad weather. Metal lenses may be more durable in certain situations, but generally there is nothing wrong with plastic lenses in this regard.

Although you pay a bit of a price for better construction lenses (both in dollars and in weight), it’s worthwhile in the end, since you may save yourself from needing to buy a replacement.

6. Lens Image Quality

There are dozens of image quality factors that make some lenses better than others. I’ll go through the most important below.

First, though, keep in mind: lenses with extreme specifications are more likely to have compromises than their relatively ordinary counterparts. I’m referring to everything from superzooms to lenses with especially wide apertures. Although compromise can take many forms, it usually means lenses with lower image quality or a higher size/weight/price.

6.1. Sharpness

Right or wrong, the top feature on everyone’s mind when a new lens comes out is sharpness. The good news is that modern lenses are sharper than ever. The limit of sharpness in your photos is very likely to be your technique, not your lens.

Today, every new lens is sharp at f/8 in the center.

On top of that, most new lenses are sharp at f/8 in the corners. The same is true at their maximum aperture (whatever it may be) in the center.

The main area where modern lenses can be unsharp is at their maximum aperture in the corners of the frame. This is hardly relevant to most photographers. If you’re shooting at f/1.4, you’re likely to get a shallow focus effect. And in that case, the corners wouldn’t be sharp anyway, so your lens’s corner sharpness is irrelevant. (Milky Way photography is one exception. If you’re not a Milky Way photographer, you probably don’t need to worry about corner sharpness at f/1.4.)

Personally, my primary concern with sharpness for landscape photography is that the lens remains sharp in the corners at f/8 to f/11, my most common aperture range. Although almost all lenses pass the “acceptable” threshold, some do better than others. I don’t care about small differences, but a bad lens here will not end up in my bag.

6.2. Distortion

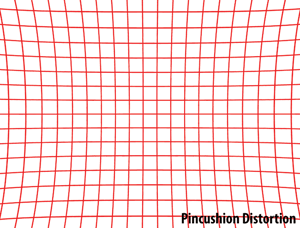

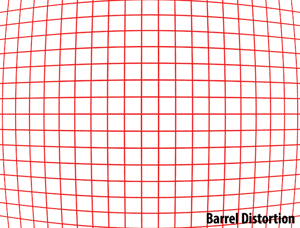

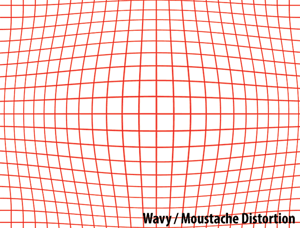

Distortion means that the lens introduces a “bulge” or “pinch” to straight lines in your images. The most obvious example is a fisheye lens, which has dramatic levels of distortion (specifically barrel distortion). If you photograph the horizon or any other flat line in your photo, a high distortion lens will show noticeably curvature or waviness.

The three main types of distortion are pincushion, barrel, and mustache. A depiction of each is below:

Although it’s not great to have a high-distortion lens (aside from fisheyes), this is hardly the most concerning image quality issue out there. Most photography software has built-in distortion correction that can fix the problem in one click. This can harm corner sharpness a bit, and change your composition slightly, but that’s a small price to pay.

6.2.1. Perspective Distortion

One type of distortion you’ll hear about is called perspective distortion, but it’s not the same as the distortion above. This one is not an image quality issue; it has to do with stretched-out proportions in your subject that can happen if you get too close. It’s especially visible if you use a wide angle lens, since you need to get much closer to your subjects than with a telephoto:

This is why most portrait photographers prefer an 85mm lens rather than a 24mm lens for headshots. You can fill the frame with your subject in either case, but you need to get far closer to your subject with the 24mm. This introduces a lot of perspective distortion.

6.3. Chromatic Aberration

Despite the intimidating name, chromatic aberration really does just mean “color problem.” It refers to color artifacts a lens introduces, like red and blue fringes in the corners of your image. Here’s an obvious example:

The example above is called lateral chromatic aberration. There is also such a thing as longitudinal chromatic aberration. In that case, out-of-focus regions are the ones changing colors. Specifically, they get greener behind the subject and purpler in front of it:

It is easy to correct lateral chromatic aberration (the first one) and harder to correct longitudinal chromatic aberration. Most photography software will have some tools to help minimize it, however.

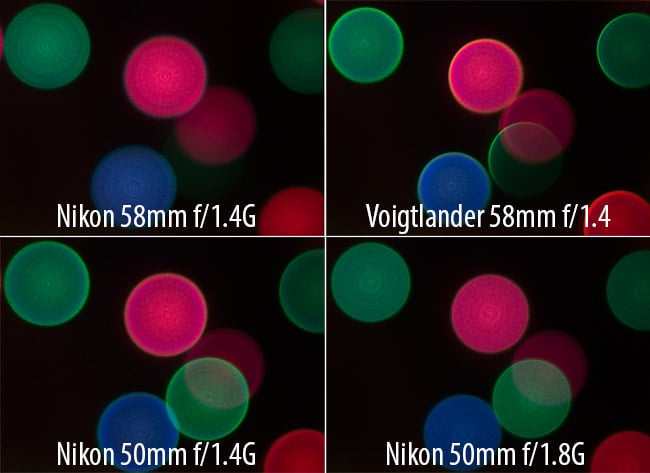

6.4. Bokeh

If you shoot shallow focus photos, bokeh will be an important concern for you. This is simply the quality of a photo’s out-of-focus blur. It was once a very specific photographer in-group term, then Apple used it in a commercial, and now it’s pretty widespread. Nevertheless, you may want to check out our full article on the subject.

Some lenses have better bokeh than others. You’ll read about it in any reviews of those lenses, no doubt. Bokeh is generally considered to be good when it has minimal texture and soft transitions, although all photographers have their own preferences.

6.5. Flare

When you point your lens at the sun, it has the potential to create internal reflections or flare that shows up as blobs in the photo. Bright sources of light can also reduce the photo’s overall contrast and make it look too hazy.

The best lenses will have high-quality coatings that minimize flare. It doesn’t apply to every photo, but it’s a big deal when you’re working in a backlit environment. As a landscape photographer, this is definitely one of my main concerns when considering a new lens.

The sun doesn’t actually need to be in your photo in order to introduce flare. Sometimes, you can get dots of flare just by pointing the lens vaguely toward the light. Although this is a good reason to use lens hoods, it’s also a good reason to buy a lens with minimal flare.

6.6. Sample Variation

Another component of image quality is sample variation – the idea that all copies of a particular lens fall within a similar range of image quality. It would be very frustrating to read a good review of a lens online and find that yours isn’t nearly as impressive.

Some lenses have smaller sample variation than others. This is something we try to include in our lens reviews by testing multiple copies of the same lens, but there is also plenty of luck involved. If one in ten copies of a lens is bad, most reviewers will never notice, but a high percentage of users will.

There’s no great way around sample variation, aside from testing your lenses. If you find that one or two corners are significantly less sharp than the others, that’s the best indication of a bad copy of your lens. See our articles on what to do when you get a new lens and on lens decentering.

6.7. Other Image Quality Concerns

Along with the list above, there are plenty of more specialized image quality concerns when you get a new lens: focus shift, field curvature, starburst performance, astigmatism, and so on.

However, the more you concern yourself with incidental image quality differences between lenses, the farther you move from real, practical concerns. It is not that these features are unimportant, but that they are only worth worrying about if a lens is far outside the norm on any of them.

7. Third Party vs Name Brand Lenses

Alongside lenses made by camera manufacturers like Nikon, Canon, Sony, and so on, countless third-party companies make lenses, too. Are these ever worthwhile choices?

On one hand, if a third-party company makes a lens that your camera company does not, it obviously is worth considering. For example, Sigma makes an 18-35mm f/1.8 zoom lens – note the wide maximum aperture of f/1.8 – for APS-C cameras. It has no equivalent from the camera manufacturers.

But many third-party lenses are similar or identical in focal length and maximum aperture to lenses from camera companies. In that case, the third party lens is usually (though not always) less expensive. Is it worth saving that money, or are you paying for third-party lenses another way – through their lack of quality?

In this case, it very strongly depends on the lenses in question. In general, third party lenses have a bit more potential for autofocus issues than name-brand lenses. They also do not always have immediate compatibility with new cameras, or camera firmware updates (although their manufacturers usually release compatibility as soon as possible).

To me, these issues are relatively minor. I generally ignore them and compare the lenses on other features instead.

For example, how good are reviews for each lens? Does either choice – name brand or third party – have poor sharpness, flare, distortion, or other issues?

Although a lot of third-party lenses several years ago had the reputation of low manufacturing standards and bad image quality, that has largely changed today. My favorite wide angle zoom is a Tamron lens (the 15-30mm f/2.8), and my sharpest lens is a Sigma (the 50mm f/1.4 A).

You still need to do your research. There are some bad third-party lenses floating around, just like there are some bad name-brand lenses. Most – but not all – will be the companies’ older offerings.

But I’ll go ahead and say that the average, new third-party lens is no better or worse than its equivalent name-brand lens. Some are better, some are worse. You don’t have anything to fear by going this route, if it suites your budget and your photographic needs.

8. Conclusion

Hopefully this article gave you a good understanding of lenses – how they work and what to look for when you buy one. There’s a lot of information to digest, but lenses are worth learning. In many cases, they really are the most important piece of camera equipment you can buy.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to let me know below and I will try to get back to you!

this was a great, informative read! thank you!

Thank you for your detailed explanation, it helped me a lot as a beginner.

Really helped me a lot. Thanks for this article.

Excellent article, thanks. As an aside, and this is not your fault, Spencer, is the annoying ads on the PL site. I get that the ads help fund the site, but when they change to the degree where the text of the article gets shifted up and down, it’s incredibly annoying. The PL site is one of the worst I have ever seen in this regard.

Having the text constantly move up and down is annoying and distracting. Please fix this.

Artur, thank you for letting me know. See my comment to Mac earlier. We hate ads that move the text just as much as you do.

You are right, that is very annoying. Our ad network periodically gets “bad advertisers” who sneak in ads like that. We report them, they get banned, and a couple months later the cycle tends to repeat. Any time you notice, please let me know. It’s not something all visitors see, luckily. Personally I’ve been free from those ads for several months, for whatever reason.

Spencer great article, wish I had the information you provided when I started buying lenses, I can think of several that would not have made the grade. My question is; how much testing goes on by the manufacturers to ensure that their lenses meet their published specifications. And, should retailers be offering their own confirmation that your brand new expensive lens does indeed perform as advertised. I ask because I seem to read a lot of articles on how a certain lens may have a high failure rate with say focusing and needs to be re-calibrated or returned to the manufacturer. Why should the consumer provide quality control after making a purchase based on published specifications. Do they work on the assumption that many of us might not notice and if we do, that is why they provide a warranty? If it is up to the consumer perhaps a future article on how to verify your new lens performance?

Quality of a lens isn’t just a matter of the lens itself. The issue of sample variety is a real issue that is a function of the camera AND the lens. Most people don’t factor the camera into this equation, but it has to be. And, even more critically, the user and how the combo was shot has to be taken into consideration. Many are arrogant and assume flaws are an issue of a faulty lens, or camera. This really gets messy when one starts using teleconverters. Some assume that there are “good” and “bad” teleconverters. In truth, this is usually more a function of sample variation AND people not taping into the camera’s capacity to address these issues – AF Fine Tuning. Oversimplified, lets say that a combo mis-focuses only front to back (not the only dimension of faults). Let’s say you have a camera that is -5, and a lens that is -5, the combo may seem to produce soft results – uncorrected. While a lens that is +5 on the same camera will seem miraculously sharp. Using the correct tools and AF Fine Tune, it is possible to adjust for these differences. When you add a teleconverter, things get that much more complicated, since you have a third device that can be off. Because of three, things can be very off, so that without AF Fine Tune, AND without manual focus, it can be challenging to get really sharp images. Most will just conclude the teleconverter is “a bad one”. Most of the time, the user has failed to evaluate the combo and make the correct AF Fine Tune adjustment.

One quick way to check a combo is to use a high contrast three dimensional subject, shooting on a tripod, with good technique (highest ISO possible, but high enough shutter speed to minimize photographer induced camera shake, and lowest aperture possible. Defocus, then take a shot using AF, then repeat three or four times – at a couple of different distances. While at each distance – turn AF off and manual focus using your best technique. Then compare the images at 100% view, or one pixel in the image to one pixel on your screen. If there is a big difference between the focus distance between AF and MF, that combo could likely benefit from AF Fine Tune IF you primarily use AF when you use that lens/camera combo.

Good luck!

A discussion about internal focusing lenses will be nice, as would a brief foray into construction (metal vs. “plastic”). And while I know they are somewhat subjective, some space should be given to weight and size.

Thanks for the feedback, Nick! I added a section on lens construction.