On my expedition to the Ecuadorian Andes, an interesting group of cameras gathered in the thickets of the montane cloud forest: a Canon EOS R5, a Nikon Z9, and a Sony A1. Since it was often the case that all three cameras pointed their lenses at the same bird at the same time, I started to notice differences in how they dealt with each given task. I found that the cameras in question detected birds’ eyes in different – and, to me, surprising – ways.

First, a brief introduction of the cameras under discussion. Aside from the oldest of the trio, the Canon EOS R5, these are the most powerful and most expensive mirrorless cameras from each brand. Even the EOS R5 is arguably Canon’s most similar camera to the Z9 and A1, since the more expensive Canon EOS R3 has a lower-resolution sensor. So, this trio represents the current kings of the high-speed, high-resolution mirrorless camera world.

Importantly for this article, all three of the cameras also feature the much-discussed feature of automatic animal eye detection. Since the Canon EOS R5 is the oldest of the three cameras, it was also the first with animal eye AF features. After an initially awkward entry into the world of mirrorless cameras with the EOS R, Canon pulled a real ace out of its sleeve with the R5 and R6. Those cameras became legitimate professional tools and are still best-sellers more than two years later. Their excellent eye detection of animals, including birds, certainly plays a role in their popularity.

As for Sony, the A1 appeared approximately six months later. Although Sony cameras have been using eye AF since 2013, it wasn’t until the A1, that bird’s eyes officially were added to the list of recognized subjects.

Finally, we have the bird eye AF newcomer, the year-old Nikon Z9. The earlier Z6 and Z7 only recognized the eyes of dogs and cats – but birds came next, and that’s when the switch from DSLR to mirrorless started to make sense to me. The high demand for the Z9 is evidence that many photographers see it the same way as I do.

So here we have three top cameras. In order to make a fair comparison of autofocus performance, it would be good to have comparable lenses mounted. By happenstance, this was mostly true during my Ecuadorian expedition. My colleague with the Canon had the RF 600mm f/4 permanently glued to it, and the Sony and Nikon both had the latest 400mm f/2.8. To extend the reach, we often, though not always, supplemented the 400mm lenses with 1.4x teleconverters (specifically the built-in TC in the case of the Nikon).

At the beginning of the article, I suggested that the behavior of the cameras surprised me to some extent. And while that’s true, most of the time the focusing worked flawlessly. But I won’t get into that too much in this article, or it would start to feel like an advertisement. Rather, I’ll share with you the moments where the AF systems faced a challenge.

In our review of the Nikon Z9, in the section on continuous focusing, I mentioned that the Z9 focuses most easily on the eyes of birds that look like a typical bird. That is, something between a sparrow and a hen. In these cases, the Z9’s algorithms are nearly flawless and can find the bird’s eye with the brilliance of a skilled anatomist. Birds that fall into this morphological box are fortunately in the vast majority.

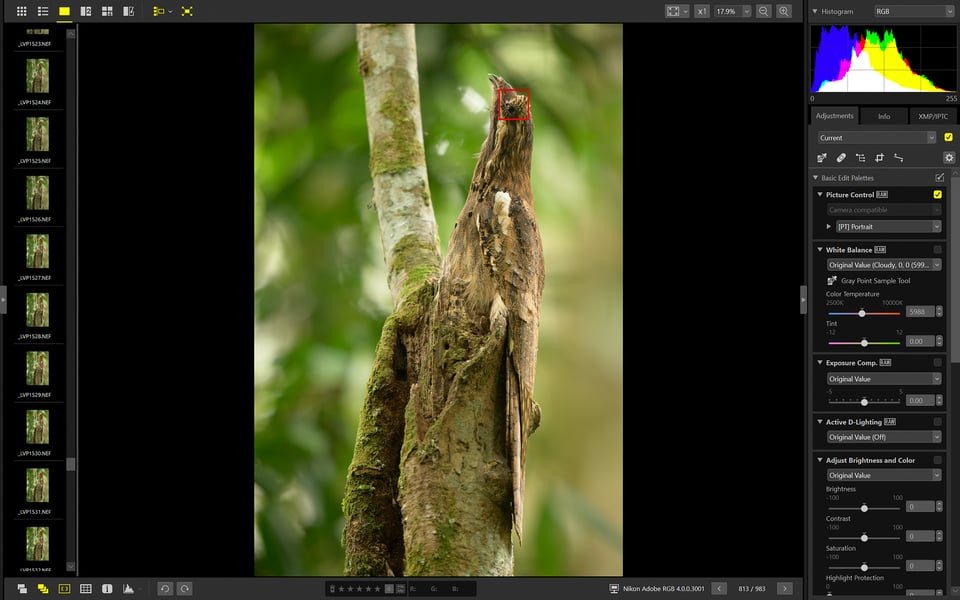

But then there are birds that resemble “typical” birds only very distantly, and these can trouble the focusing system. For example, a Woodcreeper moving along a tree trunk is sometimes difficult for AF to identify. Not that it ignores their existence completely – but the Z9 indicates that it’s focusing on the entire bird, not pinpointing the eye. This situation most often occurs in really poor light at the edge of the day, when the bird also occupies a relatively small area in the viewfinder.

It wasn’t just a Nikon problem. From the occasional mutterings of the Sony photographer next to me, I noticed that our cameras tended to fail on similar birds, and certainly neither AF system was flawless in this regard, no matter how good they usually are.

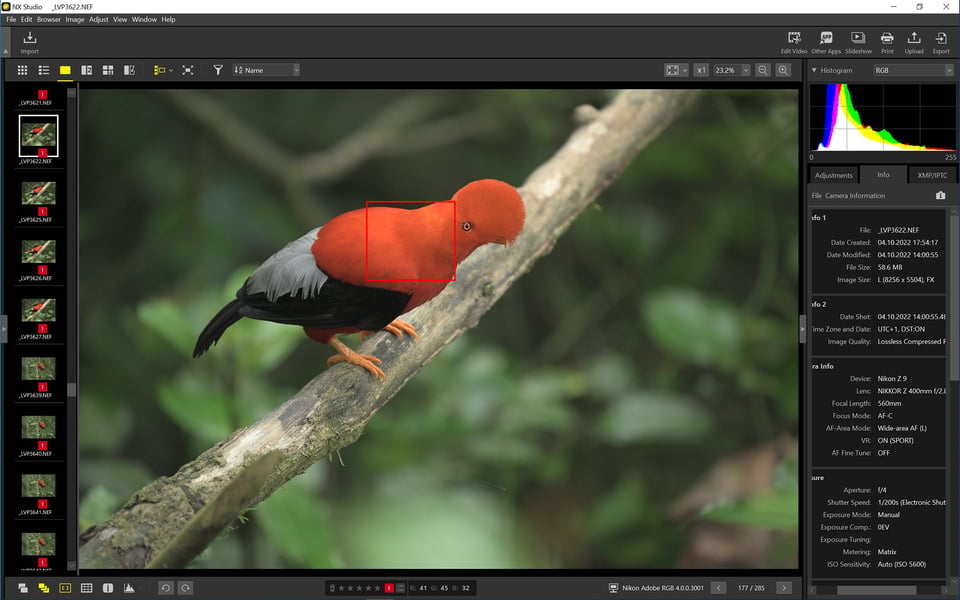

Perhaps the most frustrating experience for both of us was photographing one of the iconic species of the middle Andean slopes, the Andean Cock-of-the-rock. Its name may give the impression that it resembles a rooster, but it doesn’t at all – just judge for yourself.

The males of the Andean Cock-of-the-rock seemingly lack a beak. Of course, they do have a beak, it’s just hidden beneath their fancy crest. Another unusual feature is their color. On the eastern side of the Andes, it is deep orange; on the western side, it’s red. So, most of the bird is only rendered by the camera sensor’s red color channel! The females of this species are obviously impressed by the unique appearance of the males. Our cameras were not.

The problem is that the males start their mating display before dawn, when the forest is pitch black. And just when it looks like you might get to some reasonable ISO values, the show is over. Fast lenses and good autofocus systems really come in handy here.

How did our trio of cameras perform? At this point, as an otherwise happy Z9 owner, I would like to write that my camera outclassed all the others – but that wouldn’t be true. Nor can I give Sony fans a nod this time, despite the otherwise excellent A1. When I was shooting side-by-side with a colleague with the A1, we kept asking each other questions: “Is your camera focusing on the eye?” “Not a bit, man!” “Me neither!”

It is amazing that a bird whose eye shines into the forest twilight like a lantern is so difficult to detect for the systems of two of the most advanced cameras in the world. Of course, it wasn’t that the cameras didn’t focus at all! It was just that the eye-detection system rarely pinpointed the eye like it would with most other birds. As the lighting conditions improved, the autofocus of the Z9 and A1 both gained ground and would lock onto the eye more often, but still not every time.

Instead, it was my colleague with the oldest and cheapest of the trio of cameras, the R5, who fared the best. When asked about the reliability of the focusing on the eye, he responded happily almost every time. His R5 apparently paid more attention to biology lectures; the Andean Cock-of-the-rock simply didn’t present as much of a challenge for Canon as it did for Nikon and Sony.

The AF settings of all three cameras were comparable. We mostly used a narrower focusing field, or a single point, to pre-focus on the bird’s body. Then we used another button to activate a wider area, like Wide-area AF (L) in my case. This is a reasonably effective way of focusing in situations where the bird is in a tangle of branches, and too wide a focusing area could lead to the lens focusing on a branch in the foreground.

To rule out the importance of our skill levels as photographers, I also checked the autofocus behavior of the cameras on a standardized subject. This time, I was the one focusing each time. There is a very accurate Andean Cock-of-the-rock relief on the wall of the Angel Paz lodge. The color, the shape, the stance, everything matches reality. (Well, except for the size, which is significantly larger than life.) With the aforementioned cameras, I tried to focus on the eye.

Canon found the eye immediately. Nikon didn’t recognize the bird as a subject at first and focused on the rest of the wall. After a bit of convincing using 3D tracking, it finally found at least the head. The Sony A1 also didn’t lock onto the eye.

It’s possible that there are some birds which would cause the opposite AF behavior, where the Canon EOS R5 is the one that fails while the others succeed. But I never saw an example of that in the field. The EOS R5 focused on the eye of every bird we found, at least.

Still, as a Nikon Z9 owner, I was more than happy with the camera’s performance most of the time (and my colleague with the A1 felt the same about his camera). I was sometimes shocked at what kind of creature the Z9 could correctly identify as a bird. Some species of South American birds are so cryptic that they can reliably fool the human eye, and even the keen eye of a predator. Among the greatest masters of camouflage is the genus Nyctibius, or Potoos. These nocturnal birds seek out places during the day where, once perched, they look like the end of a broken branch or tree trunk.

We photographed one fairly rare member of this genus, the Long-tailed Potoo, in the Amazon rainforest. Yet even this secretive inhabitant of the forest’s darkness wasn’t a challenge for any of the three cameras in terms of eye-AF.

So, I will end my article on a positive note. Despite the incredible variability in bird shapes, sizes, and colors, all of today’s most advanced mirrorless cameras can pinpoint their eyes with aplomb. There are a few exceptions for the most unusual-looking birds – and I was impressed that the oldest, least expensive EOS R5 came out ahead with the Andean Cock-of-the-rock specifically – but all these cameras are very reliable overall.

There’s also a chance of firmware updates improving these issues – who knows? I’m always learning new things about bird biology, and Nikon, Sony, and Canon can too. I look forward to going back next year and seeing how things have changed.

What about you, Canon EOS R5/R6, Sony A1, or Nikon Z9 users? Have you come across any species of mammal or bird where your camera failed to find the eye? I’d love to hear about your experience in the comments below this article, and I think other owners of these cameras will, too.

I use the Sony A1 and 600mm f4 with the 1.4 tc for peregrine photography. Even with a very long range target – and the bird tiny in the frame – this setup amazes me at its ability to find and hold onto the eye of a falcon. Even in poor UK light.

Finding out (from this article) that the AI eye detect is optimised for birds of prey, this makes a lot of sense now!

Earlier this week, the same setup struggled to find the eye of a juvenile bittern near a reed bed in very harsh backlight conditions. Not only was this a much more challenging environment than a peregrine against a clear sky, it would seem that the target bird in this case is not an A1 strength.

But if wildlife photography was always easy… 🤣

Great article as a dual system user Nikon Z8 and Canon R3 the Z8 is pretty good but not as good as the R3, Have you tried the new 4.1 firmware on the Z9? I’d like to stick with only 1 system but as of now can’t decide as I’m leaning towards Nikon because of the awesome lens range and affordable (just got the Z 180-600 and it’s pretty good, Also have the Z 400 4.5) But also leaning towards Canon because of the pretty good focusing system but their lenses are not like Nikon the RF 100-500 is good but Canon needs more, I’ll wait and see what the R5II brings and also the rumored RF 200-800 before I make a decision.

I’ve recently acquired the new Z800mm lens and coupled with the Z9 it appears to latch onto various birds eyes most of the time. I recently had an issue with a brown coloured bird not finding focus at all. I eventually had to focus on a post near by and then back to the bird. Last weekend I downloaded firmware V 4.0 and it will be interesting to see if the AFC 3D mode has improved at all. I’m still very pleased with the camera and the new lense.

Great! The 800mm is a wonderful lens for birds. I also tested the new firmware a bit this weekend, but I wouldn’t dare say there’s a significant improvement. I only had one body and it’s hard to judge. The 3D tracking improvements should address situations where the detection doesn’t recognize the subject and the AF relies solely on color, distance, structure, etc.

It would be interesting to have a similar comparison with the next tier down cameras from these manufacturers. Specifically, the R6ii, A7iv and the Nikon Z6ii..

Sony says the subject recognition in the A1 was built on small birds and hawks/eagles. So it’s not designed for all birds. Long-necked ones may cause problems.

In general I start with small non-tracking lock and switch to tracking.

I have the Z9 and shoot wildlife weekly and have no issues with it finding the eye on birds whether it be Ospreys, Eagles or smaller birds. The native z lenses work better than the F mount and u need to have all your settings set up properly as well Is it perfect , no but I have not found a perfect cAmera. I do like the Sony A1 focusing capabilities for sure but the Nikon menu system is much easier for me.

Cock-of-the-rock would fall into the small bird category, but I admit it’s a pretty bizarre creature. At Nikon, they’ve obviously thrown long-necked birds into the AI pot. Swans, herons and cranes are easy targets for the Z9.

Having just returned from the Pantanal, I can attest that the R5 does not detect the eyes of jaguars: perhaps confused by too many spot markings. It also struggled sometimes with the eyes of giant river otters: a dark eye against a dark pelt with often no discernible sclera. Similar with tapir. My overall impression was that the R5’s eye detection was noticeably better for birds than mammals.

Thank you very much, Graham, for adding to the mosaic. But all the animals you mentioned have their pitfalls. Like you said, the jaguar and his spots, the tapir and his bland eyes on his oddly shaped head. Likewise the otter. However, I did photograph an otter last week and the Z9 had no problem with it. Even when it was swimming in the water… meaning on the surface, not under it.

Even after 2 years my R5 never fails to impress me. Being a macro photographer I have seen animal eye focus working amazingly even on Damselflies at night with small LED light for focusing.

One is shocked by what the camera recognizes and a few moments later disappointed by the exact opposite.

It would be informative to let readers know the distence to the subject in these photos

The birds in the photos in the article were about ten meters away. However, for the eye detection to work, it is not crucial how far away the animal is, but what area it covers in the viewfinder. For example, you probably can’t focus on a hummingbird at 15 meters. If an eagle is the same distance away, the focus point will stick to the eye like a magnet.

At 10m away, what’s the depth of field of a 400mm lenses set at f2.8?

Does eye-auto focus really matter if the depth of field is greater than the the body of the bird?

Leading workshops with my Z9 in Costa Rica, the Tetons and Yellowstone this year I’ve had many experiences where eye detect works surprisingly well (crocodiles, small birds, snakes, pronghorn and moose) as well as many where it was easily fooled (grabbing iguana body or moth wing markings) or just missed (the dark eyes on dark fur of black bear and bison). Even with the frame filling power of my 800PF some eyes don’t register and you need to override the automation.

The key for me has been using wide area with eye detect on the shutter that converts back and forth to manually directed single point AFC on the shutter via a press of the function 3 button (accessible from either grip position). I use Function Settings Hold to accomplish that. Additionally I program the back AF-ON button to switch the area mode to framewide 3D tracking only while held down no matter the shutter activated area mode. That way I can switch from eye AF wide area to the precision of single point AFC or framewide 3d tracking with eye detect without removing my eye from the viewfinder. It’s flat amazing. :)

Thank you, Hudson, for your experience. I have basically converged on a similar AF setup. It’s always a good idea to keep a button in reserve to use good old unintelligent focusing when the Z9’s AI is helpless. Fortunately, such moments are quite rare.