Better technique and appropriate gear can help you take better photos, but that will only take you so far. To reach the next level in this pursuit you need to become a student of photography.

A student of photography is somebody who dives into the pool of photo history, soaks in the images of the masters, and seeks out the best work and wisdom of his or her contemporaries. A good student realizes that observing the work of others is crucial to one’s own development as an artist, not to copy those he or she studies, but to discover his or her own eye. I’m a ruthless tech geek, soaking in as much info as I can about reciprocity failure, signal to noise ratios, circles of confusion and the like. But I spend just as much time pouring over photo books from the great photographers. The kind of books I’m talking about don’t have exposure metadata listed with the pictures. That isn’t important – only the emotional impact of the image counts. A good photo makes you wonder about the subject, not the exposure settings.

With this in mind, I want to recommend four wildly differing books I’ve read in the last year that really helped my thinking about photography and how I can best find my own eye. A lot of our readers know me as a wildlife aficionado, so you might be surprised that three of the four books have no critter pics in them. The point is a good photo is good no matter what the subject, the techniques applied or the gear used. Good photography cuts through all that BS, grabs you by the collar and shakes some sense into you. Good photography inspires you and makes you want to become better. These books all helped me improve and all for different reasons. I suggest you check them out.

Table of Contents

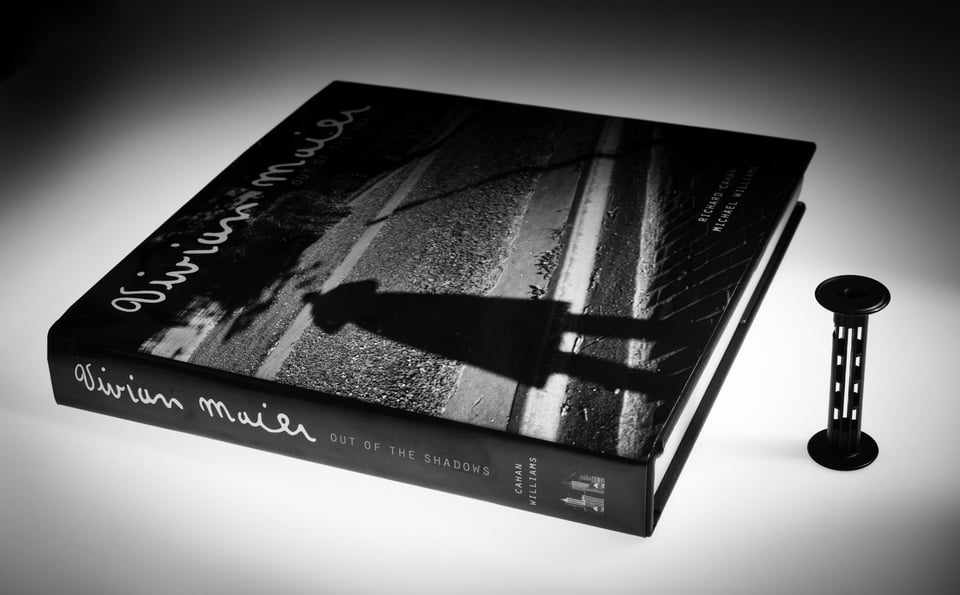

Vivian Maier – Out of The Shadows by Richard Cahan and Michael Williams

Vivian Maier’s story is odd, mysterious, and a bit creepy all at the same time. A nanny during the day, a street photographer during the day. Hang on, does that make sense? Only with Maier. So would often take her young charges into the city while she pursued her photos. I see a lot of street photography that attempts to grab your attention with gritty portraits of the down and out. Snoresville – show me something new. Maier seemingly shot anybody and everybody and she wasn’t doing it to grab attention. She was private, mysterious and often portrayed as cold and harsh. She shot for herself and only herself, never sharing her work with anyone. Her life was devoted to the process of photography, not the end result. When Maier died she left scores of rolls of 2-1/4” film she had shot, but never developed. Her work wasn’t discovered until it was found at an estate auction after her death by someone who recognized how amazing her eye was. Otherwise it might have ended up in the dump. When Maier’s images hit the internet she quickly became a celebrity, though posthumously.

While the whole story behind her photo career is pretty weird, what’s really amazing is how good her photos are. I’m not a fan of street photography but I’m a fan of Vivian Maier’s photography. Go to vivianmaier.com for a few examples. Her compositions are spot on, her sense of lighting and timing terrific. Technically she was outstanding, but so are a lot of photographers. What sets her apart is her ability to capture a moment in time and make her viewers wonder what the back story is to each shot. Maier’s shots show her as one of the keenest observers of the world around her. There’s a some bizarre undercover surveillance pathos going on. Did that make sense? Probably not. Which is why you should pick this book up and check it out for yourself.

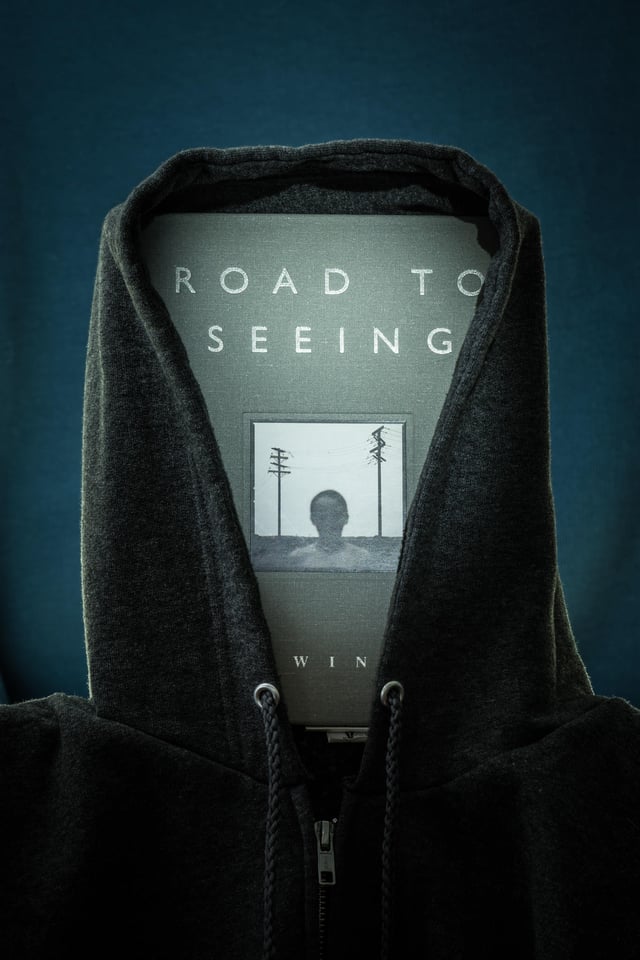

Road to Seeing by Dan Winters

I have a confession to make. I’d never heard of Dan Winters before I cracked this terrific tome open. Flipping through the pages of “Road to Seeing” I recognized many photos and was embarrassed that I didn’t connect Winters byline to the images. He’s perhaps best known for his slightly grunged-out celebrity studio portraits seen in Time, New York Times Magazine, Wired, Fortune, Esquire and other mags. He’s shot the likes of Will Farrell, Tupac Shakur, Glenn Close, Michael Jordan, Christopher Walken, Laura Dern, even President Obama and Mr. Rogers. But like a diamond, Winters has many more facets than that. He can step out of the studio and shoot hard-hitting photo essays for Texas Monthly about neo-Nazis, the Mexican Mafia or unsolved murders. He can shoot honeybees or the space shuttle. Go to danwintersphoto.com – do it now. His images will transfix your eye.

Why I recommend this book is not because Winter’s photos and skills are outstanding. They are. But rather because this is a book about being a student of photography and when to comes to that Winters graduated summa cum laude. This isn’t some egocentric babble about how Winters became commercially successful, but a look at the influences on his career, whether they be other artists or editors or something else entirely. This book features not just Winter’s work, but the work of many others that inspired Winters. You’ll be exposed to Eugene Atget, Alfred Steiglitz, Andre Kertesz, Paul Strand, Henri-Cartier Bresson, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Eddie Adams, Gary Winograd, William Wegman, Gregory Heisler and many other photography greats. But equally important are the photos he includes from lesser known photographers as well as those from “photographer unknown”. That Winters studies the works of the great as well as the works of the unknown shows he’s a true student of photography. Good work is good work whether the artist is known or not. Beyond the photographs are the stories told. You’ll learn why Eddie Adams regrets the photo that won him the Pulitzer and how Margaret Bourke-White had her focusing cloths made out the same fabric as her custom-tailored dresses. You realize because Winters knows the images and knows the stories, that that contributed hugely to his own success. That is the power of being a student of photography. And now that I’ve studied Winters work, I’ll be a better photographer and student as well.

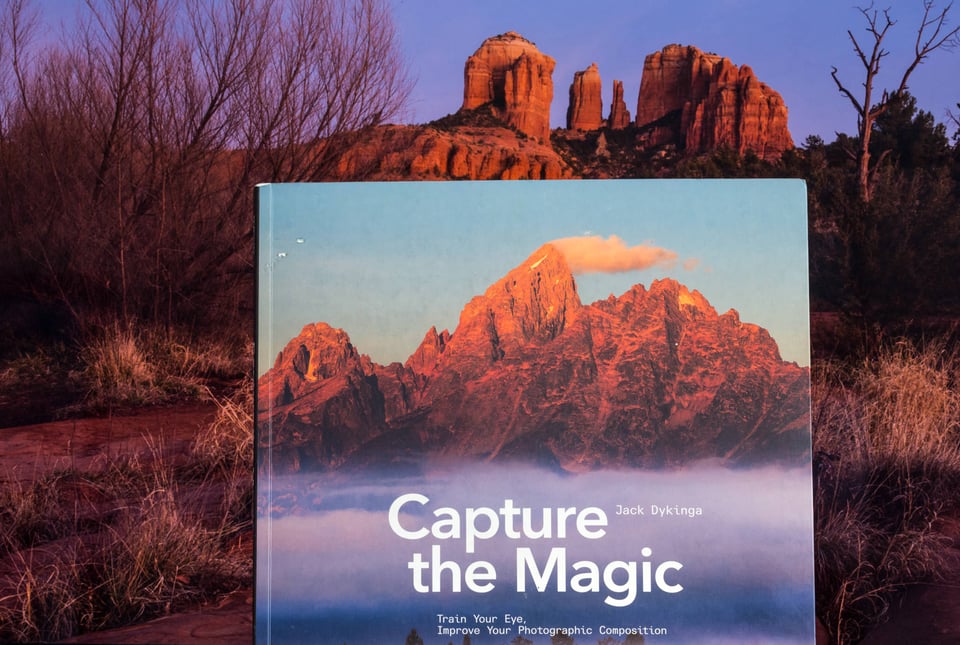

Capture The Magic – Train Your Eye, Improve Your Photographic Composition by Jack Dykinga

Sometimes I wonder why Arizona Highways doesn’t just save ink by declaring “all photos in this issue by Jack Dykinga unless otherwise noted.” Dykinga has been a mainstay of American landscape photography for decades. In the book 100 Greatest Photographs to ever appear in Arizona Highways magazine, 12 of the images were Dykinga’s. Ansel Adams? Only three. Check dykinga.com for a taste.

One could easily mistake Capture The Magic as a coffee table book. Heck, I don’t speak or read Swahili, but if this book were only available in Swahili I’d still get it just to look at the inspiring landscape photos. What I like about Dykinga’s images is that despite how gorgeous the final result is I still feel like I’m viewing a photo taken on the same planet I live on. I can’t say as much for many of today’s landscape photographers who seem more intent on flexing their Photoshop muscles than on revealing nature’s truth and beauty.

While the subtitle “train your eye, improve your composition” may make you think this is just a how-to book, it is much, much more. Sure there’s a ton of practical advice in it’s pages, but what I dig is while it’s a lot about how to do photography, it’s just as much about how to think about photography. This is not about exposure triangles, color wheels, and the Golden Mean; it’s about the process beyond that – light, composition, timing, perseverance, feeling. I’ve already read it cover-to-cover twice. If the book in the product shot looks a bit worn it should – I keep my copy in my van and whenever I’m out on a shoot and feel my composition is getting stale, I’ll thumb through it for inspiration or maybe a specific tip or two to get me out of my rut.

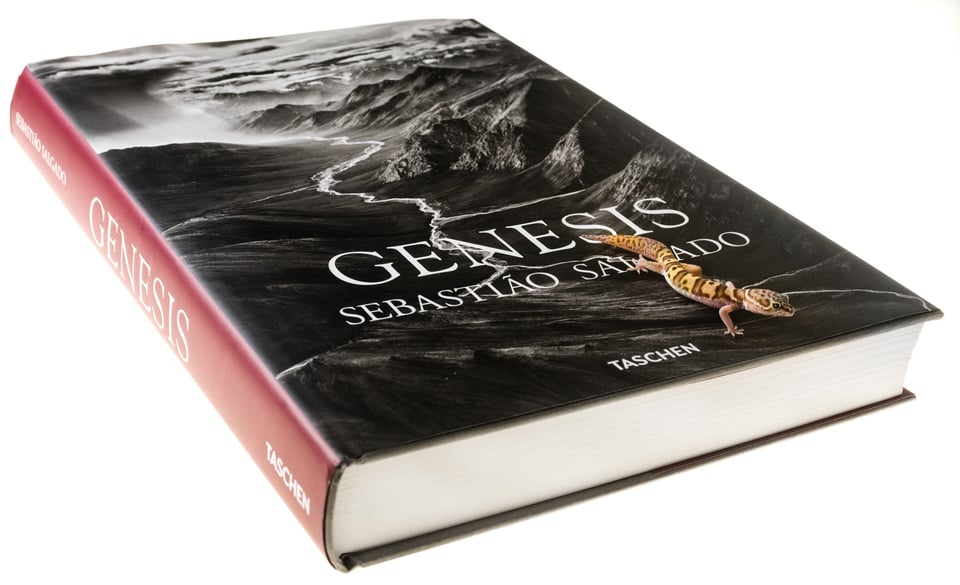

Genesis by Sebastiao Salgado

I can still remember the first Sebastiao Salgado photo I saw – it was a huge open pit gold mine with long rickety wood ladders emerging from its depths. What looked like armies of ants cling to the sides of the pit were hundreds of half-clothed workers hauling sacks of dirt and rocks up the ladders. The conditions looked abominable and though there were hundreds of workers in the photo, you had to wonder what story was behind each and every individual. What cancer of the human condition could result in such a barbaric enterprise at this stage in history? How bad could life be that so many men toiled under these conditions? Such is the power of superior photojournalism.

With Genesis, Salgado steps aside from his usual subjects – embattled and disadvantage populations – and turns his camera toward our planet as it was before the dawn of “civilization”. His stark high contrast black-and-white images feature landscapes and wildlife in a way to show Earth as it was before humans screwed it all up. It also features a number of indigenous tribes yet to be modernized, but already slipping away from mankind’s hunter-gatherer roots by slashing and burning the rainforest to make way for agriculture – the first step on the slippery slope to where we have taken our planet.

Genesis is a huge book on a huge subject. As I stated above, Salgado’s eye can suck you in with a single image. This book is full of stunning photography, perhaps too much. Trying to view it in one sitting would be like trying to eat an entire cow at one meal. While Salgado’s photos may make you want to become a better photographer, more importantly they make you want to become a better person. Can there be any higher praise? Expose yourself to Salgado at www.amazonasimages.com.

Contents ©John Sherman

Thanks for the great article – I saw Genesis in the book store just before Christmas and was grateful to see it under the tree this year. Another great read which I stumbled upon recently is “It’s Not About The F Stop” by Jay Maisel. Great read and follows a similar theme to your article.

Hey John! I think Vivian was alive when her locker was sold at auction. And by the time they found out whose photos they were, she had taken a fall and passed. Great photographer. I saw the documentary at the Boulder International Film Festival, and brought my Rolleiflex, which was a big hit in the street after the show. Great to read your work and see your pics!

Hi John,

do you know this book? Creative Nature & Outdoor Photography by Brenda Tharp. If yes? How it compares with the books you described in this article?

Thnaks

On Sebastião Salgado note do watch the documentary “The Salt of the earth”

Great list! I only have one of these (Jack Dykinga, soooo good!) I went to Dan Winters website (never heard of him, but recognized his portrait of Nicole Kidman). I will order his book. I really thought his portraits had a depth that is hard to really describe. I will look more carefully when I get the book, and try to understand it better. I love photography like that because it draws you in emotionally. There is a vision there that I am positive I can get something from.

Great review! Makes me want to read all four books.

I agree wholeheartedly that the emotional impact of an image is what matters.

Here are a some of my favorites that aren’t mentioned in the article. Feel free to use these in a part 2 or append them as a “suggestions from readers” list if you want.

50 Portraits: Stories and Techniques – Gregory Heisler

Heisler shares 50 iconic portraits of celebrities, athletes, and world leaders, along the fascinating stories about how the images were made, often including alternate shots, lighting setups, and other information. One of the best books I’ve seen for learning the creativity side of portraiture. While Heisler primarily works with large format film, the discussion is primarily about creativity, workflow, and thought process.

The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression – Bruce Barnbaum

While it is organized like a textbook for a class, this book is immensely readable and enjoyable. Both digital and film photographers will love it. Equal time is spent on technique as on creativity, composition, and photographic meaning.

Magnum Contact Sheets – Kristen Lubben

Contact sheets are used in the editing process. I enjoyed this book because it shows a rare glimpse into all the work that goes into choosing and creating a “great photo” outside of the camera. This book is incredibly thought-provoking, and will make you want to crack open your archives and see what gems you’ve missed.

Thanks for adding to the list Bob! I like how Barnbaum pretty much put Antelope Canyon on the map and did it in black and white.

Excuse me John, you’re right, it’s CREATION of course. I had the paperback copy but managed to get the larger hardcover later in Maine, was worth the extea buck. Re looking at other photographer’s work: of course books are no substitute to going out and making photo’s, Neil. Gulping down information unconsciously in the wrong belief that it is a substitute for experience is one of our modern society’s main dilemma. However, a great piece of art communicates on consciously deeper (or higher) levels and can help us to connect to that in ourselves. A master of a chosen tradition, like photography, is someone who has transcended the path that got him/ her there and Salgado has done exactly that. Master’s help students become masters and vice versa. And for that we need to be exposed to each other’s work if it happens in a social context.

I think it depends on each person’s temperament. Some people really do photography for the sake of art and spend a lot of time executing their vision and there are people who see that work and are moved by it.

People like me, though, have other motivations for photography so seeing books on art and art theory is interesting intellectually but doesn’t do much for what I enjoy photographing. It is interesting to me, though, that most of what is considered fine art seems to be primarily centered in street photography and sometimes very stylized versions of landscapes/portraits.

I’m curious as to what subjects you photograph Neil.

Mostly wildlife, family, astrophotography (not landscape) , and the occasional landscape, portrait, and travel stuff. When I frame a photo it’s not with some fine art detail in mind. It’s for a composition or subject that appeals to me. If there is an email address for you somewhere I would be happy to send you a link to my flickr page.

Thank you John for the recommendations. I had the pleasure of being at an exhibition featuring the works of Sebastiao Salgado here in Singapore. One word, breathtaking.

Thanks and I’m envious – I have yet to see Salgado’s work in a gallery. Which is another great way to gain inspiration. It’s one thing to see work reproduced in a book and some reproductions are better than others. But when you see the actual print in a gallery there can be so much more depth. I remember seeing Joel-Peter Witkin’s prints in person and being absolutely floored. I was so transfixed by the depth and richness that I couldn’t turn away and it forced me to confront Witkin’s uncomfortable (well not for him, he see’s beauty in it) subject matter in a way no book could.

Agreed John. As you have so aptly put it, there is so much more depth and richness to a print in a gallery. It was indeed an inspirational experience, one I sincerely hope you get to experience yourself.

In the end I don’t think any book makes you a better photographer. A book, even on composition or theory, can give you more tools in your tool belt (best case) but the only way to be a better photographer is to get off your duff and work on it. These books can be entertaining or enlightening but I find that only certain personality types seem to actually get anything more out of it than another coffee table book.

Agreed on your first point (that wasn’t my title for the article). Of course you need to get off your duff, and I find pouring through books and studying great photography encourages me to do just that.