The questions are as old as the technical advancements that made the mass reproduction of photographs possible in the first place: What are the role and scope of photography? What is it capable of, where do its limits lie? Which contents are acceptable, how does a photographer need to behave with his or her subjects? The relationship between photographers and the people they capture with their cameras has been discussed on numerous occasions, mainly in the context of war or crisis reporting. Social taboos, artistic freedom and the journalistic mission to document are key elements within this ongoing discussion. Objectives, goals and ethical guidelines have to be newly defined over and over again.

Note: Please read the Importance of Ethics in Photography before reading this article.

NIKON D300 + 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 @ 105mm, ISO 200, 1/320, f/10.0

I attempt to become as totally responsible to the subject as I possibly can. The act of being an outsider aiming a camera can be a violation of humanity. The only way I can justify my role is to have respect for the other person’s predicament. The extent to which I do that is the extent to which I become accepted by the other, and to that extent I can accept myself.

James Nachtwey

The arena for this debate is not confined to newsrooms, academia or ethics commissions. One example from popular culture is the movie “War Photographer” about the work of famed photographer James Nachtwey; the documentary raises questions such as “how close (e.g. to a grieving war widow) is too close?” or “when is taking a picture identical with the denial of assistance?”.

Canon EOS 5D Mark II + EF24-105mm f/4L IS USM @ 32mm, ISO 100, 1/60, f/4.0

Another example is Wim Wender’s “The Salt of the Earth”, through which the audience follows Brazilian star photographer Sebastião Salgado on a journey through pain and disillusionment. We listen to his recounts of the genocide in Rwanda and famines all over East Africa, while looking at heart-wrenching photographs of starving children and piles of mutilated corpses.

Canon EOS 5D Mark III + Canon EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM @ 67mm, ISO 800, 1/60, f/2.8

The question American essayist Susan Sontag poses in her last book, “Regarding the Pain of Others”: To what end do we need those kinds of pictures? Do they induce empathy? Or do they simply satisfy sensationalism, are they a modern form of voyeurism? Another urging question that has occupied media and audiences for many months: can one, should one, does one have to showcase and distribute the current horror images of the IS and its atrocities? Do they shed light on what’s happening on the ground or are we, by sharing them, complicit in spreading the propaganda of criminals? To speak with Susan Sontag again: “The photographer’s intentions do not determine the meaning of a photograph, which will have its own career, blown by the whims and loyalties of the diverse communities that have use for it.”

Canon EOS-1D Mark III @ 16mm, ISO 800, 1/3200, f/2.8

Beyond these rather established ethical questions there is, however, another, less frequently debated one: what does the photographer, does a media outlet, does an audience actually owe to the subjects in a photograph? To give an example: doesn’t it seem right that part of the profits made from Steve McCurry’s famous 1984 National Geographic cover of the Afghan girl with the green eyes would have gone back to the young refugee, her family or community? Naturally, the photographer alone would not have been able to take a picture as captivating as this without her face, her intense gaze, her story.

My point is this: When talking about ethics in photography, can we afford to stop short of asking the most primal question of all – whose picture is it, really? Not legally, but morally speaking. Is it enough of a “payment” to, for example, document a human rights violation and get it published?

Canon EOS-1D X @ 55mm, ISO 2000, 1/250, f/2.8

Many of our photographers at Photocircle have chosen to opt for something I would call a double payback: they donate parts of their proceeds to support social projects in the places where the pictures were taken, and at the same time dedicate their photographic work to raising awareness of the various injustices of this world.

Canon EOS Kiss X3 @ 23mm, ISO 200, 1/80, f/22.0

For instance: Ingetje Tadros. Through her documentary style of photography, she confronts and provokes to convey a message by telling people’s stories. For her project “Caged Humans in Bali”, she won the UN Association of Australia Best Photojournalism Award in 2014. Her photo series tells the story of Pasung, a method used to restrain the mentally ill in Bali: “I’d sent everybody outside, away from the scene, and I stayed there alone – sometimes with a person chained to a bamboo bed, dribbling and making strange noises. To be able to sit there definitely changed me, as I said to myself: this needs to be told, I need to get this out in the open.”

NIKON D5000 @ 180mm, ISO 1600, 1/30, f/5.0

Just recently, she also won the 2015 Amnesty Australia Media Award for her story “Kennedy Hill” about an Aboriginal community in the remote town of Broome in North West Australia. The community exists in the shadows of Western Australian Premier Colin Barnett’s commitment to close down up to 150 Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. “To me”, she says, “the most important thing is that the people in the story agree that I tell their story – this makes it powerful; it gives them a voice.”

So when all is said and done: what does that actually mean for a photographer – “to become as totally responsible to the subject as possible”? It most probably means to make the effort of evaluating and re-evaluating every single situation, every motif, each scenario on its own. Is a certain snapshot worth entering a moral grey zone? Am I violating someone’s personal rights? Am I aestheticizing conflict or showing both sides; catering to voyeuristic tendencies or sensitizing? There is also no blanket solution to the other problem – what do we owe to the subjects? Here at Photocircle, we feel our photographers have found a good compromise to start from.

Canon EOS 550D @ 85mm, ISO 100, 1/400, f/2.0

This article has been contributed by Katrin Strohmaier. Katrin spends her days as a mouthpiece for Photocircle, a Berlin-based startup connecting photography and humanitarianism. In a nutshell, more than 600 international photographers sell their pictures on photocircle.net and with every purchase, up to 50% of the total price goes towards a social project in the region in which the picture was taken. The idea is to let the subjects benefit from the proceeds the pictures generate as well. Katrin studied communications and politics in Berlin, and then devoted herself to the Near East – on the ground at first, and later at the London-based School of Oriental and African Studies. Over the years, she brought home the bacon writing for newspapers and doing PR for NGOs, while always making sure to spend enough time traveling our beautiful planet.

I am an extremely keen Street photographer, an interest heightened when I bought into Fuji X CSC. Although I have retained all my dSLR’s (D800E/D7100) they are too heavy to cart around the streets and folks are suspicious of a pro camera pointed in their direction. That said I occasionally also use a Rolleiflex 2.8f which evokes much interest from my subjects, but as Vivien Maier found the waistline viewfinder detaches one from the subject. Fuji X is perfect, the X-T1 with it’s rear articulated screen behaves in exactly the same as the Rolleiflex.

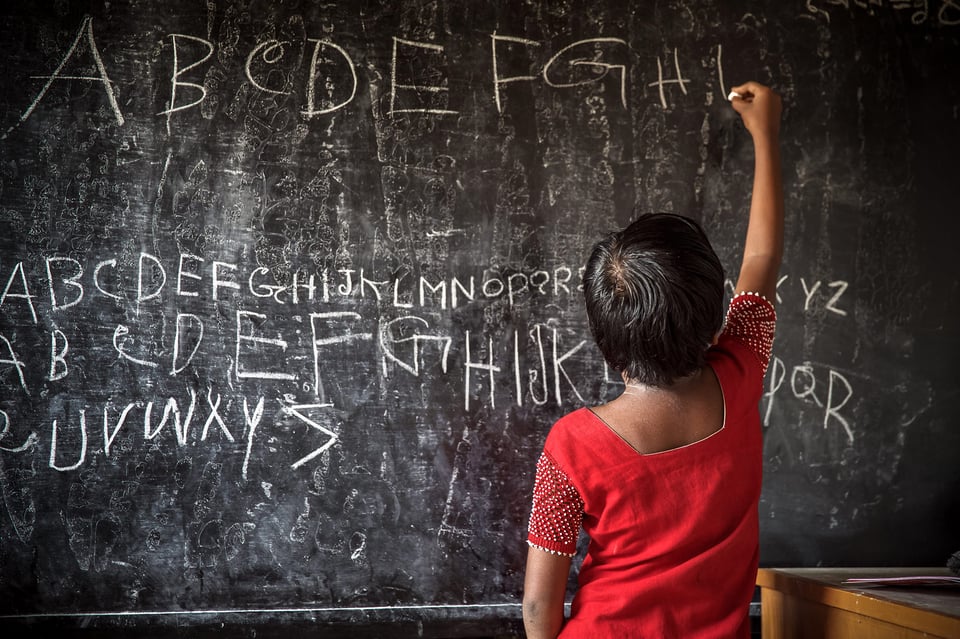

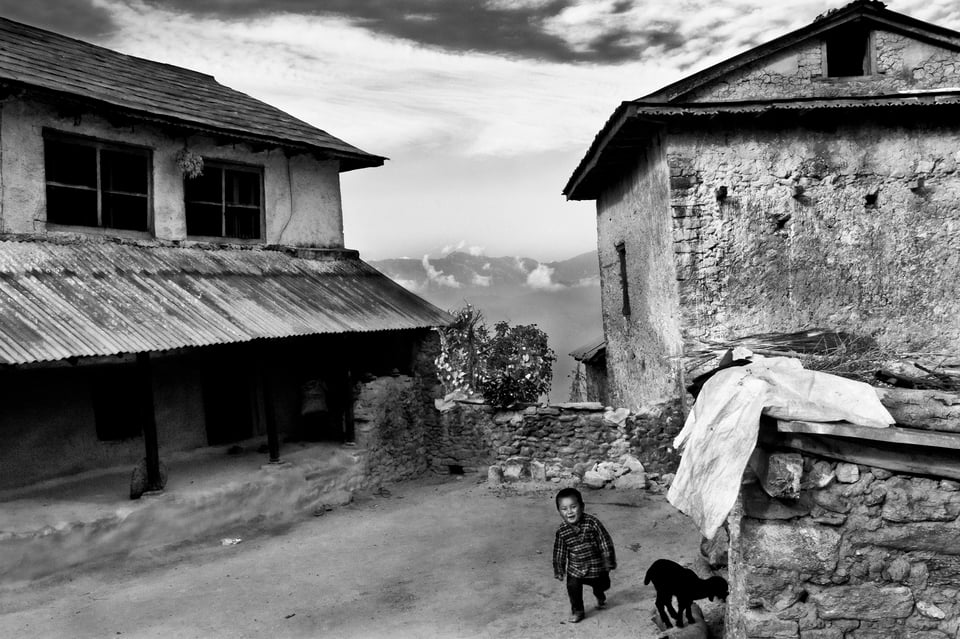

So why to I enjoy Street photography and what do I think is ethical. Firstly, I prefer to call it morally correct. I look at my images as journalistic and a record of life today. Most reside in photo books and wall mounted prints. I have only once been approached and asked not to photograph by a father with his young daughter. I actually had no intention of doing so, as for me minors are mostly out of bounds. I say “mostly” because images 1 & 9 would not be captured by me unless permission had been given, or I been asked to capture it by an adult related to, or guardian of, the child.

Referring to the paragraph above “to become as totally responsible to the subject as possible”? It most probably means to make the effort of evaluating and re-evaluating every single situation, every motif, each scenario on its own. Is a certain snapshot worth entering a moral grey zone? Am I violating someone’s personal rights? Am I aestheticizing conflict or showing both sides; catering to voyeuristic tendencies or sensitizing? There is also no blanket solution to the other problem – what do we owe to the subjects? Here at Photocircle, we feel our photographers have found a good compromise to start from”.

This is exactly how I interpret the rules of ethicasy or being morally correct and how I approach my photography. I applaud Photocircle for their moral stance.

Richard

Love those articles. Although we might not agree with some things (giving away our rights when social published etc.), those are facts that we all have to deal with.

The sad truth is that many photographers act selfishly and without any respect to the subject they are capturing. All they think about is how well it will perceived back home, how much they can get for it or how much it will propel them in the prestige department. That’s it.

I am a wedding photographer and although I don’t have to face those situations I have faced an incident at one of my weddings. Out of nowhere the families started a fist fight (bride and groom included). I lower the camera and waited for things to cool off. No one would want those photos and I have no interest in them either.

My first instinct was to keep clicking thinking it would make a great Facebook article or something like that but it did not take more than a second to realize it’s not why I am there for. Regardless how much traffic it might generate to my page, it was immoral. The bride and groom later asked me to delete images of the brawl, when I informed them that I did not take even one photo they were thankful and relived.

The other day I read of a bunch of no good morons who passed a baby dolphin among them to take selfies. None obviously cared that the dolphin cannot breathe out of the water. I guess taking selfies was so important and gratifying. It died while being passed from hand to hand.

Much of society is selfish, careless and stupid. Unfortunately, it is, in many cases, the face of the ones holding the camera, whether it’s a smartphone or a $7,000 DSLR.

Well done PL. These ethics articles are terrific and PL can never have too many of these. There are rarely clear answers and sometimes not even clear questions but I believe thougtful focus (no pun intended) on these issues is important to making us better photographers and better people. A few observations:

— I understand but don’t fully agree with comment #1 above that ethics stop where capitalism begins (my paraphrase being perhaps too simplistic to be fair). In fact, the sad story of Richard Prince from the prior article is in my mind as much about the interplay between ethics and capitalism as it is a duty to the subject (that he never knew) or theft/appropriation of images. He owed no direct duty to the subject–indeed has no relationship at all with the subject– and yet there is a profit driver in his work that ignores any ethical consideration of the unknown subject and the context in which the photo was taken.

— Katrin’s article is a thoughtful consideration of many ethical issues and, while the “solution” proposed by photocircle.net is not technically a solution to many of the identified issues, it certainly is an attempt at “rough justice” or action in the face of non-action…. so applause to her and the cause.

–PL often features landscapes/nature photos (superb, superb ones at that) and Nasim’s excellent article focuses a bit more on that. Katrin’s article is a nice compliment to that by having more of an attention to human subjects. The more nuanced of the two, for me, are issues around nature photography (what is the purpose(s) of nature photography, considering the positive and negative impacts on the subject, themes and messages vs. intrinsic beauty, even religious views on the appropriateness of visual images) and would love to see more thought provoking commentary on the subject.

Is it just me, or does that first photo (of a boy supposedly running along a pipeline) look Photoshopped? Now that would be unethical!

Yandoodan, if you mean the background haze in the top left of the photo, if it is India, Pakistan or Bangladesh, that is real. Everything stops having sharp lines from 300 feet on. Pollution is so bad you can feel it as you breath.

I went browsing on photocircle.net and found this guy: .

Made me think of this guy: www.machalowski.de/portf…iexpo.html

In light of the previous Ethics article, I wonder who inspired who?

Photography is an integral part of our lives. It changes everything. It changes the way we see ourselves, our view of the world, our ideas about what news is, celebrity, history, identity. Marvin Heifernen pulished an excellent book on the impact of photography. See: .

As far as ethics are concerned, it is about values and perspective.

The question of whether a photograph is prescriptive or descriptive depends on the audience as well as the photographer. Is it documenting and displaying or is it evaluating and approving or disapproving? I am sure there is a time and place for both. Personally I prefer the former.

We do however live in a world where the idea that one should not cast judgement about others can be measured in milliseconds. The tweets and posts on social media, slam and condemn anyone and anything with such regularity, tolerance is a commodity in short supply.

The images in the article clearly aim to provide comment as well as observation but they also show the viewer enough respect to allow them to make their own judgement. Photographs which ask questions of the viewer are always more effective than those intended to manipulate the audience.

Great article.

I should clarify. I prefer images which are descriptive rather than those which are prescriptive. (Apologies for typo… “published”

It is interesting reading your discussions on ethics in photography. I feel though that you are confusing photography with capitalism. I agree with most of what you say about the relationship between the photographer and the objects he chooses to shoot. From that point on it is a commercial transaction and there are few if any ethics involved with capitalism. The object is simply to make a profit and nothing else counts. Value is judged simply on what it is worth.

The ethics in the art of photography is between the photographer and his subjects just as religion is between the individual and his God.

Dad?