12-bit image files can store up to 68 billion different shades of color. 14-bit image files store up to 4 trillion shades. That’s an enormous difference, so shouldn’t we always choose 14-bit when shooting RAW? Here’s a landscape I snapped, then found out later I had shot it in 12-bit RAW. Better toss this one out, right?

Depending on which class you took at the University of Google, the human eye is only capable of distinguishing between 2.5 and 16.8 million different shades of colors. If this is the case then wouldn’t 12-bit be plenty? Even 8-bit JPEGs can render 16.8 million colors.

There are many upsides to shooting 12-bit instead of 14-bit. The files are smaller, hence your camera’s buffer doesn’t fill up as fast, allowing longer action sequences to be caught before buffering out. 12-bit files take up less space on your memory cards – great for if you are on vacation without the ability to download your images every night. You can save money because you don’t need to purchase as many gigs of storage. Likewise, 12-bit hogs less space on your drives at home and the same number of 12-bit files load faster than if they were 14-bit. Lastly some cameras, such as Nikon’s D7100 and D7200 achieve higher burst rates when shot in 12-bit than in 14-bit.

So if the human eye can’t discern the difference and 12-bit has so many advantages, why doesn’t everyone just shoot in 12-bit? For the same reason brides want a real diamond, not a cubic zirconia. Admiring an engagement ring from a normal viewing distance, few people can tell the difference, but give that ring to a lab technician with a refractometer and they can distinguish the two (Note to readers: I will cut off your shutter finger if you forward this to my fiancé).

When given the choice I’ve always shot 14-bit, because as an American I know bigger is better and besides it’s my constitutional right to fritter away as many redundant bytes as I please. I went to the internet (I sense trouble coming) to validate my feelings and found a lab test where someone shot a lens chart with a DX body at 4 stops underexposed then zoomed in to 200% and sure enough, you could see a difference. Then I checked another site where test shots showed no difference. This was getting confusing for my puny brain so I decided to field test 12-bit versus 14-bit to see if I could tell any difference. I started out with landscapes – if anyone is picky about file quality it’s us landscape geeks. Bear in mind that these tests are in the field, not the lab, and though I tried my best to keep all parameters the same, there may be some slight variations due to Nature and/or the tolerances the camera is built to. I shot with a D810.

Here’s a nice yucca shot in 14-bit and properly exposed.

And here’s the same yucca in 12-bit.

I can’t tell a difference.

Next I tried a shot that would test the camera’s dynamic range with sunlit clouds and a shadowed foreground. I exposed not to blow out the highlights, which then resulted in the shadows being pretty underexposed, requiring me to pull the shadow detail back up in post. Here’s the original 14-bit file with no post-processing. (I won’t bore you with the 12-bit original – it looks identical.)

And here’s the 14-bit with the shadows recovered.

And the 12-bit.

Here’s 14-bit cropped in on some shadow detail.

And the 12-bit.

Oh crop, there’s no difference I can tell. I showed this to a photographer with more critical eyes than mine and she couldn’t tell a difference either. Maybe the difference is only visible in a final print. So I printed the two versions and still couldn’t tell a difference.

So far my tests were with well-exposed shots. It holds to reason that if I were to be able to tell a difference it would be in the dark values as when you’re courting the left side of the histogram, you’re dealing with a lot less raw information. After all, in dark conditions such as underexposure, fewer photons are being counted at each pixel site than when it is bright. (See Spencer Cox’s article about the theoretical advantages of having more data to work with by exposing to the right side of the histogram.)

I was driving through Northern Arizona late one afternoon and there were some clouds so I had to detour to The Mittens. Sadly the clouds started shrinking to where I would have a mediocre sunset shot. Rather than pack up and leave, I thought “ah ha”, time to run some more 12-bit versus 14-bit tests. But this time I’ll bracket the exposures and see what happens.

Rather than go through 30 samples of original shots, tweaked in post shots, and tweaked and cropped to 100% shots, lets fast-forward to the most underexposed sample. First the unprocessed 14-bit.

And 12-bit unprocessed.

14-bit tweaked and cropped to 100%.

12-bit tweaked and cropped to 100%.

What’s a guy got to do to see a difference? These are virtually identical, especially given that this was natural light, which isn’t always even and there could be slight exposure variations due to tiny shutter speed and aperture differences. If I can tell any difference at all it might be a teensy bit more contrast in the tweaked 12-bit samples.

The above tweaking was from letting Lightroom auto-tone the images. Not really the best presentation of this file so I went in and tweaked more to my liking and applied the exact same parameters to each file.

14-bit tweaked.

And 12-bit tweaked.

Squinting real hard I’m learning two things. First, I can’t tell the difference between these 12- and 14-bit images unless I look at the metadata. Second, my 24-120 Nikkor is pretty soft in the corners – I should have shot my 50mm.

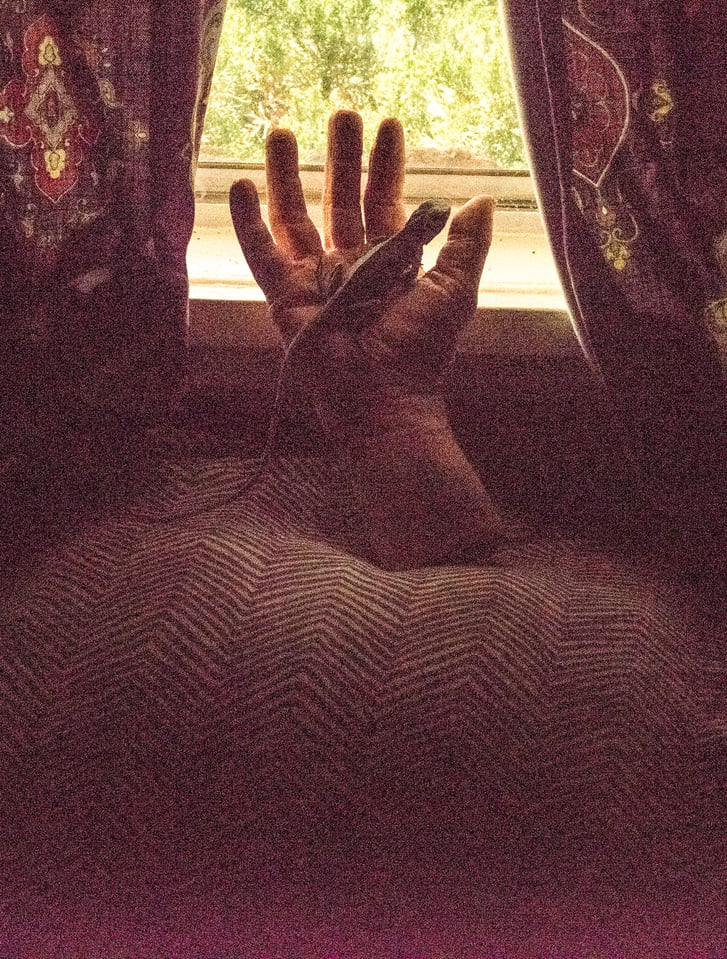

You may have noticed all of these so far are at base ISO. Maybe I need to go to higher ISOs where the camera will have to amplify the signal hence we might encounter some noticeable differences. I went inside to get low enough light.

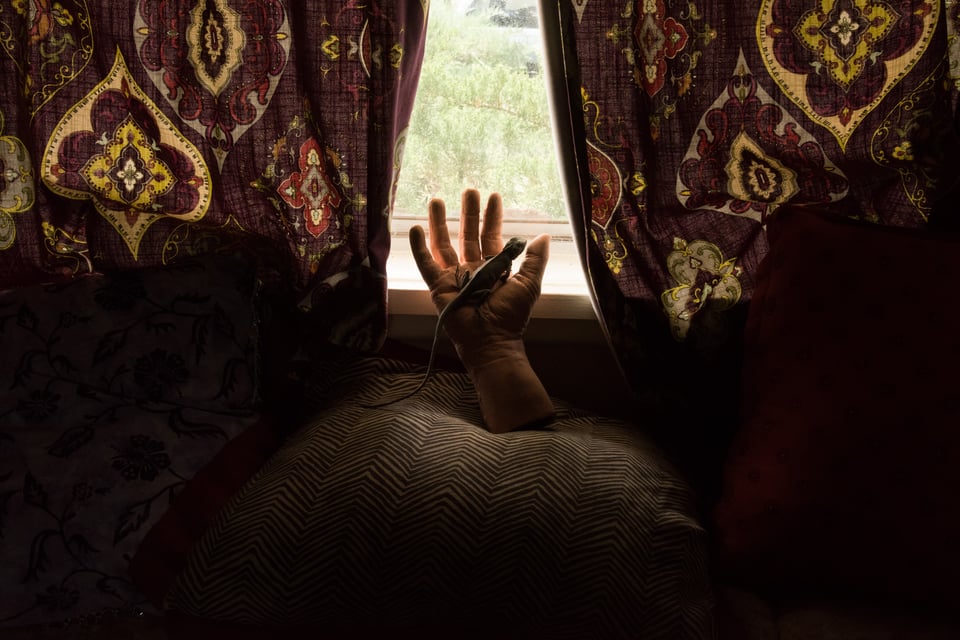

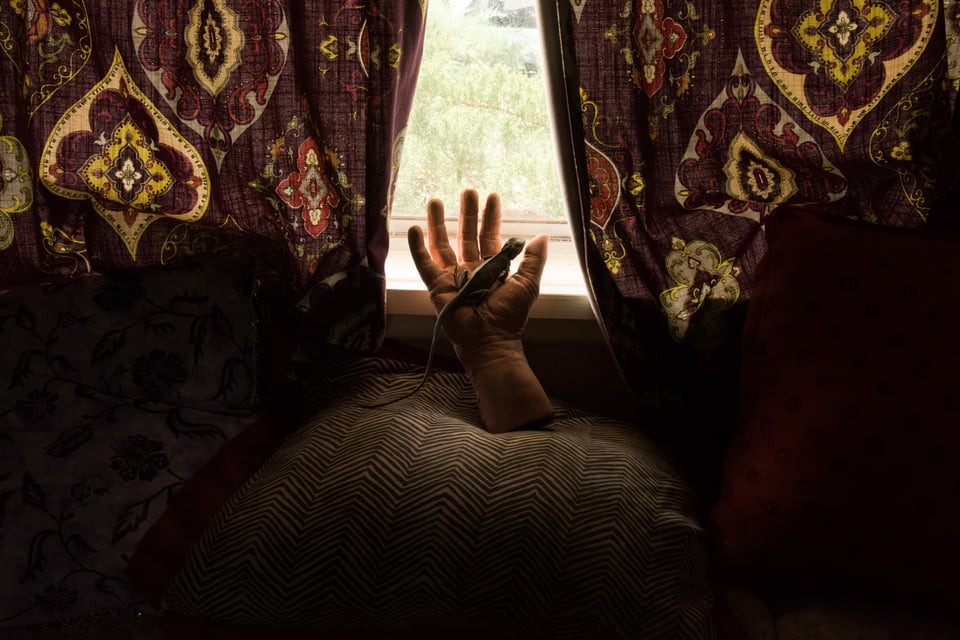

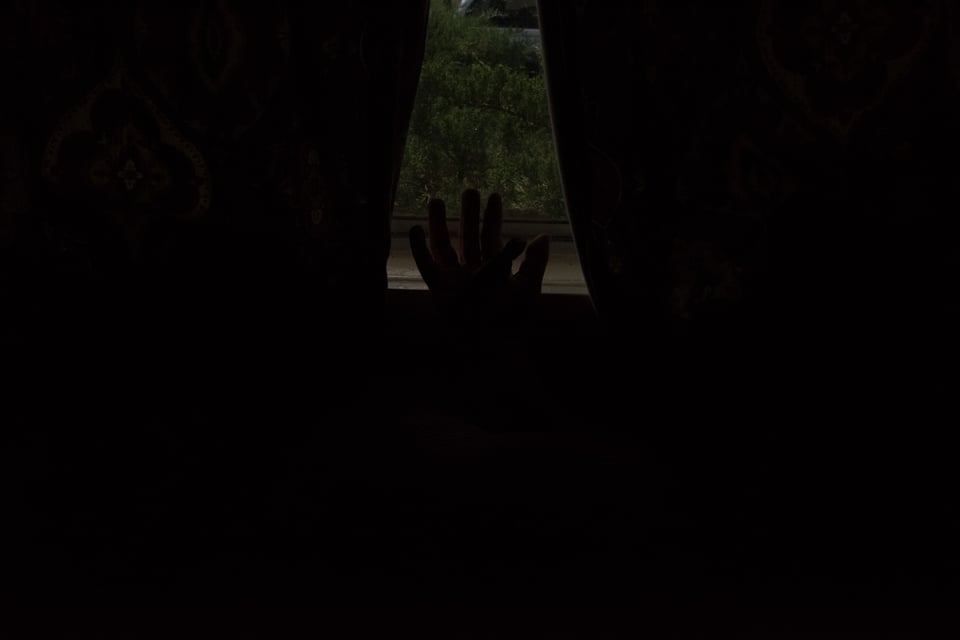

Again, instead of running you through dozens of tedious samples, we’ll cut to the chase. These are at ISO 3200. The scene has a ridiculous dynamic range from sunlit bushes outside the window to deeply shadowed pillows inside. First the untweaked 14-bit.

Now the untweaked 12-bit.

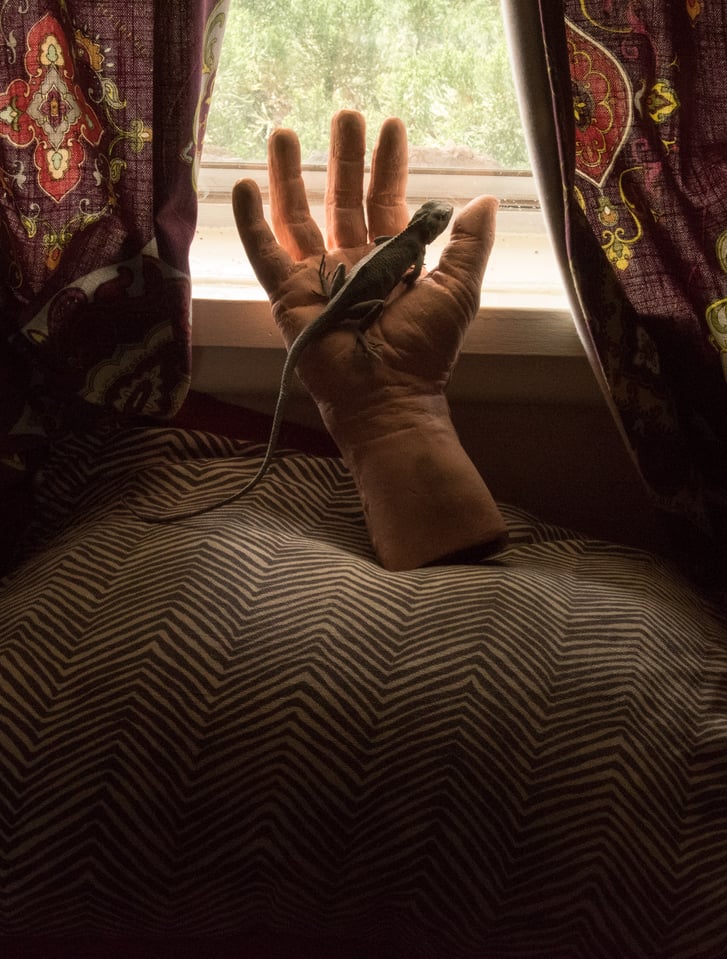

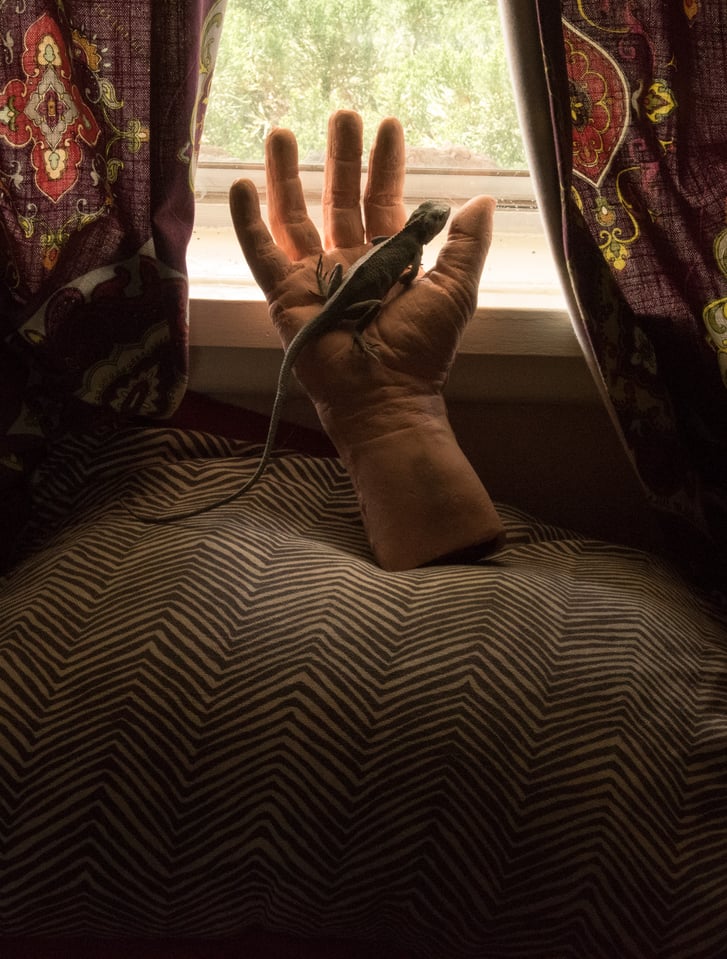

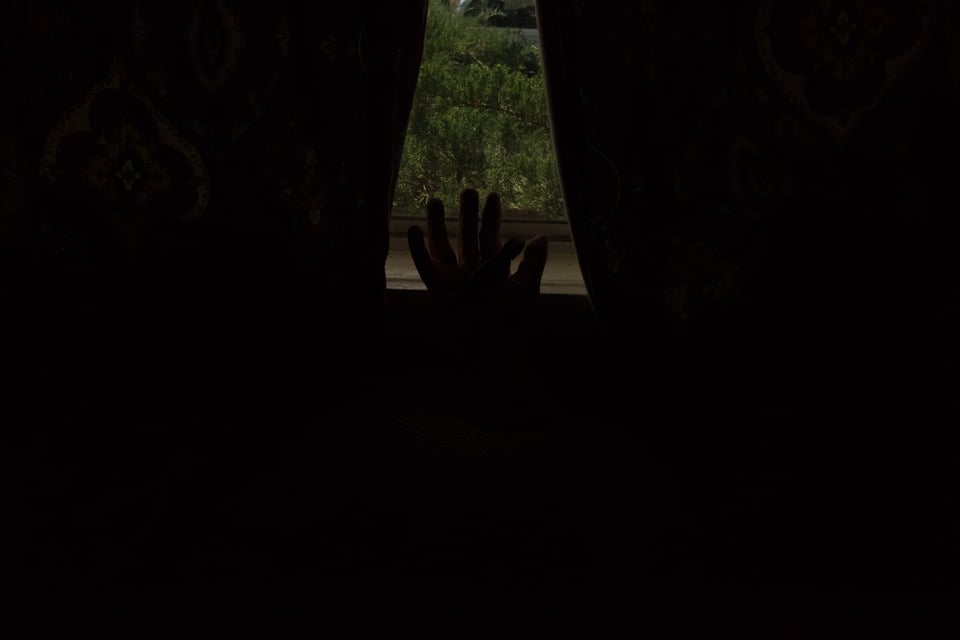

The 12-bit looks a tad brighter. The following had identical tweaks save the exposure of the 14-bit was boosted a tad to match the 12-bit. Tweaked and cropped 14-bit.

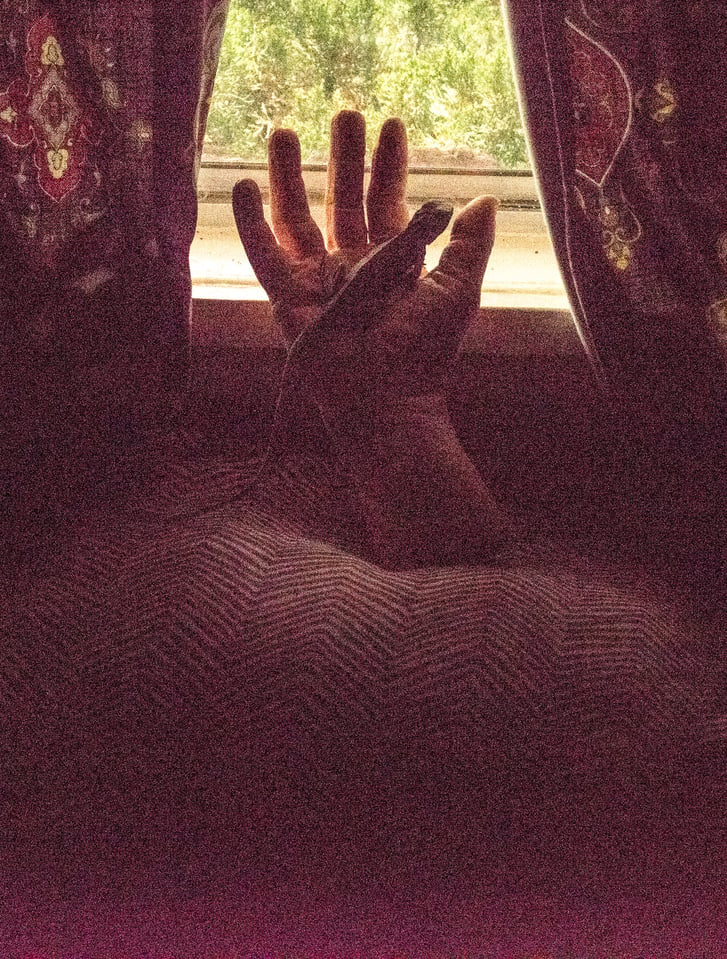

Tweaked and cropped 12-bit.

Just maybe an eensy bit more constrast in the 12-bit, but I reckon if you printed these out and swapped them around and showed them to me I couldn’t pick out one from the other.

I guess we’ll have get ridiculous and head to that special place where histograms go to die.

Here’s the 14-bit.

And the original histogram. Oh my, even Michael Moore doesn’t expose that far left.

And 12-bits of despair.

Again the 12-bit looks a tiny bit lighter so this is perhaps a 12-bit/14-bit D810 thing, not any variation in light levels or shutter speed/aperture tolerances.

14-bits cropped and tweaked.

12-bits cropped and tweaked with the same parameters.

At last, a difference I can see – the 12-bit file after extreme processing is having some trouble holding highlight detail. However I can see a tiny bit more shadow detail in the 12-bit file. This might be due to the f/16 aperture not closing as far on that particular exposure, hence letting a few more photons reach the sensor. Or maybe not. Either way, both 12-bit and 14-bit files look like they drank too much and puked all over themselves.

Let’s try again. Here’s a scene in Petrified Forest. I’m underexposing heavily and stopped way down trying to get a small, tight sunstar and seeing just how much I can retrieve from the shadows in post. (This would be a much better candidate for exposure blending, but we’re running a test here.)

Here’s the untweaked files. First the 14-bit.

Now the 12-bit.

And now with identical post processing. -100 highlights, +100 shadows, +2.45 exposure, and various other tweaks.

The 14-bit.

And the 12-bit.

At last, I created a practical field test that is showing a difference. The 12-bit version has got an unpleasant greenish cast and the 14-bit is trending slightly magenta. Also it looks like there is more shadow detail in the 12-bit. Let’s fix the color in the 12-bit shot as seen below.

Voila. Looks great now and I like the extra shadow detail recovery. As I’ve already gone to +100 in the shadows there’s no further global adjustments I can give the 14-bit without blowing out my sunstar. I’d have to do local dodging and burning to match the two.

The takeaway I got from all this is that worrying about having 14-bit files instead of 12-bit is silly if you expose well or even just don’t mess up too bad. Good post-processing can give results that make it hard if not impossible to distinguish between 12- and 14-bit files. I did these tests to mimic situations I might encounter. I encourage readers to do their own tests with the sort of subjects they shoot. Feel free to share your results in the comments section.

All said and done, will I switch to shooting 12-bit? Psychologically this tears me apart knowing my files won’t be all they can be. Furthermore I like to photograph birds. They have four cone types in their eyes versus three for humans, hence have far superior color vision, up to ten times better. What if I want to sell family portraits to this Mallard mom?

Us humans can’t see the difference, but Mama Mallard sure will. Aw, those Mallards are pretty stingy anyway. I’ll just switch to 12-bit and increase my chance of getting the shot (through shameless spray and pray tactics) rather than getting a bigger file I can’t appreciate. And I can always switch back to 14-bit when conditions dictate I should – like the next time I’m shooting handheld candlelit test chart shots and forget to remove my 6-stop ND filter.

Text and photos ©John Sherman

I’ve noticed myself on my A7Rii that the only difference is when you wanna do really extreme tweaks in good conditions or, as you also showcased here, in low light with higher ISO.

I recently shot an event (friend’s dissertation defense), and the room was quite dark. I had to shoot at ISO 2000-2500 because flash was not an option. I chose to shoot in compressed 12-bit to save some space and since this was not a paid gig, but just me shooting some pics from the audience.

Now, working in post, trying to bring up the exposure and so on, I realize I struggle a lot with getting nice contrast and colors, much more so than when I shot some extreme sunset images in 14-bit. Sunset images had some really dark shadows that I lifted, and they all looked great. Doing the same now with the dissertation photos do result in that same green tint as you showed.

Researched this very topic for years. I shoot portraits and decided to put this 12 bit vs 14bit to the test. The result was pointless. I couldn’t tell a difference. Certainly did not make the pictures better. On the contrary it created larger files and loading times. It looks more like a marketing tool for camera makers. The same goes to shooting 46 mp files and all you do is upload the pictures to social media sites.

Tnx, I was looking for this exact investigation. If 12-bit is identical to 14-bit in over 98% of cases, as you found, then 12-bit would be the much more logical qual setting for me. A fast mallard, let’s say father mallard, obviously wants to be photographed at the much faster framerates (and the smaller file sizes) connected to 12-bit. A bird’s life is only short.

Have signed up to like the author’s sense of humor 👍

brilliant

Playing around with shadows is one thing. Pushing hues/vibrancy/luminance of plants, skies, skin tones, etc especially after adjusting exposure in post is completely different. Most basic portrait/landscape photographers try to get their shots perfect SooC to where they might as well just post the JPEG and call it a day. “Artistic” photographers that can’t be bothered with “technically correct” colors will push their images through hell and back and often quickly see their colors band, crush and scream with a 12-bit file, but can make a human appear like a bright purple alien with little effort in a 14-bit file with nary a band or crush to be seen.

If you’ve never had an image fall apart on you in editing, don’t bother with 14-bit, even for your birdy friends.

The entire article is complete nonsense. If the author can store billions of colors in 12 bit he will be the richest person on this planet. Simple because the only way to do so is using qbits and must have invented the quantum computer everyone dreams of. 12 Bit stores no more than (xFFF) 4096 colors while 14 bit stores (x3FFF) 16384 colors, thats it, period. From there onwards the article is meaningless, authors gibberish fantasies.

Your math is correct for each of the 3 colour channels, so 4096^3 is over 68 billion.

RAW files do not store “colors” they only store tunes of gray from the individual pixel (which can have a red, green or blue filter). The colors are then inferred from algorithms that know the pattern of the pixels of that specific sensor. Thats why you cant just do the math simply as it would be a full RGB and the comparison “JPEG has 8 bit, RAW is 12 or 14 bit” is just very misleading.

Nevertheless, thank you for the article and for the record I dont agree with OPs rude sentitment that “I DONT LIKE ONE THINK IN THE ARTICEL THERFORE THE WHOLE ARTICLE IS BAD”.

Old article, but in case anyone will read it these days, like me, and will read my comment: 1 all of your JPGs are compressed 8-bit. So you might as well have shot JPG. Also, sombre dispay devices can benefit from higher bits, but even then 12 bit is plenty for most daily shooting, even if you plan +/-100 edits in Lightroom. So why 14? Because it’s not only possible to go beyond +/-100, but often necessary in certain situations. In astrophotography, we often recover faint detail to the tune of +1000. When you do that, it tends to crush the light in areas being compressed (this is why in Photoshop you take your photo and put it into a 16- or even 32-bit file. Once you’re happy with your edited results, your can easily take your photo back down to 8 bits. Which is plenty for viewing and printing.

I could see a difference the the monument valley shots. More dynamic range with the 14 bit.

I can see the difference in every comparison. Maybe it’s the quality of my iphone display, but the 14 bit files have wider color gamuts and higher color resolution that is plainly visible. They also have more highlight detail and a wider dynamic range. Perhaps you need a 600nit+ display to see that difference as well as a properly calibrated and capable rendering of 0 – 16 shadows. I’d expect these differences to be even more pronounced on a high quality true 10 or 12 bit display.

I also eat lots of lutein, so my eyes may well be in better shape as well.